Why Develop a Nutrient Management Plan?

Developing a nutrient management plan can be a large undertaking. And once it is completed, implementing it puts a livestock producer well on the way to environmental stewardship. A plan may be written for one or more purposes: to satisfy regulatory programs, to qualify for financial assistance or maybe just to gain peace of mind.

The plan should have been developed in close working relationship with the producer, and in so doing, many of the management practices that needed improving will have been worked out and the producer understands the need for the practices and is willing and capable to achieve the items as detailed in the plan. No plan will ever be followed exactly as it was written as weather conditions, soil conditions and market fluctuations create a constant flux for any farming operation. But as these changes arise, the producer who has been involved in the development of the plan is also skilled in how to make changes that continue to be in the spirit of the plan for environmental protection, nutrient accounting and conservation needs. The plan is then teamed up with records that show the plan is either being followed, or documents any deviations.

Also check out the archived webcast on Improving Implementation of Nutrient Management Plans |

Strategic Planning

The planning process needs to include strategic (long term) and tactical (annual) planning. A strategic plan needs to be developed for the whole farm. The strategic plan articulates the policies and guiding principles for the entire farm operation. This type of plan needs to present clear concise statements that reflect the farm’s commitment to conducting operations according to the plan. A good starting point is to create a Whole Farm Nutrient Balance Report This report will provide the farm with a snapshot of the nutrient flows onto and off of the farm. The ideal scenario would be for the nutrients imported onto the farm in feed and fertilizer to be balanced by the nutrients being removed in commodities that are sold off the farm. For farms that have more nutrients than the farm can deal with the options to consider include, reducing purchased inputs (fertilizer and feeds), moving nutrients off the farm, through manure or compost, acquiring more land or reducing animal numbers.

Once the farm knows where it stands with regard to nutrient balance it can begin to formulate the strategy needed to deal with the situation. Farms with too few nutrients or just enough nutrients needed to meet crop requirements can take a straightforward approach to developing a strategic level plan for the farm. In these situations the farm simply needs to commit to making maximum use of the available nutrients by applying the nutrients to a crop field when the field needs the nutrients and at a time of year when the crop can take them up. On the other hand the farm that has too many nutrients has a more complex problem. This farm also needs to apply nutrients to fields needing them when the crop can take them up, but it also needs to develop a strategy to deal with the excess nutrients.

Annual (Tactical) Planning

Plans should be reviewed annually, to see how closely last year’s actions matched the plan, to make any updates to the plan and to project ahead for the next twelve months. This annual update is the time to input any new soil tests, develop the coming crop rotation, document yields, add new fields or delete ones no longer farmed, update animal numbers and incorporate new manure analysis. If major changes are being planned or have occurred, the plan may need significant changes.

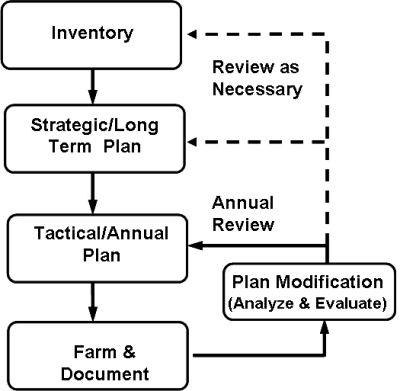

These factors will keep the plan current and meaningful. Conceptually, implementing a nutrient management plan can be thought of a cyclical process composed of a series of steps. Due to the continuous nature of farming several of the steps in the cycle may be happening simultaneously, but for clarity we will consider them one at a time. The figure below shows these steps and the cyclical arrangement of their relationship to each other.

There are instances where the annual/tactical plan can be functional for the coming year, but the strategic/long range plan indicates that annual planning will become more difficult each year. For some farms, it may be easy to nitrogen base the plan, but coming into phosphorus balance will be more difficult, or impossible. P-index strategies should be considered a short term solution; but when a farm is generating more phosphorus than it can utilize, eventually, a P-index strategy will lead to over applications of phosphorus and potential concerns in the years to come, especially if regulations and policy tightens nutrient planning in the future. There will be situations where livestock numbers increase on an operation but there is less land base in the neighborhood. Scenarios such as these, point to the importance of considering both the long term and the annual planning process.

Communicating the plan

Implementation of a plan often hinges on communicating the plan to other family members or hired employees. First, the farm owner needs to show, by his/her actions and words, that the plan is important. Next, a system of communications to the farm employees on what they should do to follow the plan and reporting back, by the employees, of what they have done needs to be put in place. If the farm doesn’t place sufficient value on the plan then the workers will have no incentive to follow the plan and it will collect dust on a shelf.

The tactical/annual plan will be a field-by-field, day-by-day, plan that needs to be communicated to the farm employees or family members. For some workers, training may be needed to impart the skills required to farm under the constraints of the plan. For example operators of manure spreading equipment may need to be taught how to adjust tractor gearing or throttle settings to obtain spreading rates as defined in the plan. This section of the plan will require things like:

- Field 1 needs 2000 gallons of liquid manure applied per acre in the spring.

- Field 4 needs to be harvested by September 1 in order to establish a cover crop to protect the slope from erosion during winter.

- Field 25’s soil P levels are above threshold levels, no manure can be applied.

- Field 6 needs 200 lbs. of potash.

Records of actions

In return, there needs to be a track record of what did occur, noting any changes to the planned activities. Records are critical to the process because they provide the proof that the plan is being adhered to, as well as valuable information to be used in the formulation of the following year’s plan. If your farming practices are questioned by a regulatory agency or an unhappy neighbor, your records may be your only defense.

There are a number of websites that can provide sample record keeping forms and field worksheets that can be used as is or modified to meet the specific needs of the farm. A couple of suggestions to get started are:

- Nutrient Management Plan: Records Checklist and Samples for Animal Feeding Operations

- NRCS Sample Records

Analyze & Evaluate

This section of plan implementation is where crop records get put to use. One needs to analyze the records kept, to determine on a field by field basis how closely the plan was followed. If the records deviate substantially from the plan the farm needs to provide a reason for the deviation. These explanations need to become part of the permanent crop records so that if someone looks back at the crop records he can obtain a clear picture of what happened and why. The farm may have experienced a wet spring and needed to remove manure from storage to avoid a discharge, but the only field that was dry enough to work had already been spread. By determining what happened and why, the farm presents a rationale to outsiders that it is being environmentally responsible.

Evaluation is the final determination of how well the plan worked. After the individual field comparisons are completed, summary information should be calculated to provide a report card on the nutrient management practices as a whole. It is this summary information that can point out the weak points in the plan. For instance, if fields consistently yield less than the yield goal in the plan then adjustments need to be made. If a number of fields are increasing in soil P over time the application rate for manure or fertilizer may need to be lowered to reduce the accumulation of P.

This management information is the hidden benefit of the NMP process. Detailed farm records will allow farms to use input costs, production data, operating costs and revenues to conduct cost/benefit analysis on production practices. This will allow the farm to see which aspects of the operation are helping or hindering profitability.

Another aspect of evaluating a NMP is to do periodic checks on practices and procedures. Farms need to take a proactive approach to quality control in the area of nutrient management. Manure and fertilizer spreader calibrations will change over time. Farm personnel will begin to forget practices and they do not perform the same task in exactly the same way every time. Field conditions can vary due to weather.

For these reasons farms need to conduct periodic spot checks of manure and fertilizer application. Results from these types of measurements can be used to verify how accurately practices are being followed, and will provide a measure of confidence for the accuracy of the farm’s records in the event of a complaint. For example, if a complaint were filed stating that the farm misapplied liquid manure, it would be in the farm’s best interest to not only produce the crop records to show what was applied, but also to show a series of spot check results, that showed that the applications made on the farm that year were accurate to within plus or minus a real number of gallons per acre. Knowing this confidence interval can provide an extra measure of assurance that the farm actually applied what it said it had.

Implementing a nutrient management plan on a farm can be a daunting task. There is a lot of information to be managed. There are decisions to be made and records to be kept. You don’t need to do it all at once. See what specific resources are available in your state and use this web site to provide suggestions that you can tailor to suit your situation. When a plan is written and implemented correctly a farm can learn a lot about itself, and how to position itself to be in business over the long term with a minimal environmental foot print.

Page Manager: Richard Meinert, Extension Educator, University of Connecticut

Reviewers: Rick Koelsch, University of Nebraska and Doug Beegle, Pennsylvania State University