Purpose

Timber Creek Recycling has operated a turned windrow composting operation using manure and food waste processing by-products and green waste for over a decade in Meridian, Idaho. Pressure from suburban encroachment and the availability of increasingly difficult feedstocks that had excessive odor, created the need to move operations from a farm to an industrial site. Land costs were greater, and potential odor impacts would increase in this move. The owner also requested that the number of touches be reduced to minimize the current workload for compost operators. There are some essential operational & design considerations to manage manure composting on a concise footprint and a limited budget. This presentation describes the operation and design considerations that can apply to any composting operation.

What Did We Do?

Green Mountain Technologies considered three different models of concise composting. Radial stacker bunkers, using a central pivot telescopic conveyor to place and cover active compost piles. Also inwardly turned circular aerated piles, which use a side discharge compost turner to turn the compost towards the center of a large circle. Timber Creek Recycling decided to use a narrow profile rectangular shaped turned aerated pile composting approach. This form uses a long concrete aeration floor that allows the owner to build capacity in six phases and increase the operating efficiencies with each additional phase. This approach kept the expansions in line, so that delivery trucks could unload directly in front of the piles and so that side discharge compost turners could be used to mix feedstocks into one side of the pile and move the composting material through different aeration floor capacities and finally to a long collection belt that directly fed a compost screener. This and the aeration floor reduced touches from 12 to 9, compared to non-aerated windrows, and provided a once a week turning frequency, reducing compost, and curing time from 90 to 45 days.

Steps taken to reach this point.

Industrial land was purchased in Nampa, Idaho, permits received and phase one of construction has been completed and operated for over 9 months. The design compacted a 30-acre operational site to a 12-acre operational site with significantly more capacity than the original. Odor reduction steps were taken to reduce the odor of cheese whey waste activated sludge being delivered to the site by using a lime additive during the screw press step at the cheese manufacturer. A small straddle windrow turner was used to mix the delivered feedstocks, and a food waste de-packager was installed to manage out-of-date or off-specification foods.

What Have We Learned?

The use of reversing direction aeration was not necessary when using positive aeration using a cap of wet wood chips or screened compost covers on top of the piles for the first 7 to 10 days. Odors have not been a problem at the new site using forced aeration compared with turned windrows (un-aerated) at the old site. The higher horsepower side discharge conveyor compost turners do not make economic sense just for phase one but will for all three phases. Wastewater collection and reuse is difficult to manage and needs to be incorporated into the mixing and turning process using an underground main and hose reel located at the far end of the aeration pads.

Take home messages

Aeration using blowers and airpipes below a concrete floor can effectively keep composting operations with challenging feedstocks from smelling bad and increase the biological efficiency and throughput. Use of a woody moist bio cover over the top of the pile is essential for the first 7-10 days for these feedstocks.

Force air through a compost pile at least 6 times per hour using on/off timers to control pile temperatures between 125° and 145° F and to keep oxygen above 13% using a rate of 3-5 CFM/cubic yard. Automated temperature feedback controllers make this simpler and more dependable.

Turn and re-water at least 2 times in the first month, either by top irrigation within 30 minutes before turning, or using a hose reel and spray bar connected to the turner (better) or simply turn piles at least 30 minutes after a big rain event.

Piles shrink over time- Double up the piles after 2 weeks and cure with less forced air at 1-2 CFM/cubic yard for an additional 2 weeks.

Adding capacity over time without increasing travel distances requires delivery directly to the initial composting area and collection from the distant piles using conveyors. On-farm generated feedstocks and the composting operations should be placed together as close as possible. Have delivery and storage of outside amendments be alongside your manure or processing waste discharge locations.

Each touch of the material should be limited, and with each touch involving several key feedstock preparation actions while entering a composting system, such as metering materials together in the correct proportions, and mixing thoroughly while watering and delivering into the first composting stage. Examples include building windrows proportionally with loaders and turning and watering with a windrow turner that can apply pond wastewater as it turns. Second example, if a conveyor is used to collect and discharge a manure in a CAFO, add bulking materials prior to the last conveyor and place into an in-line pug mill before stockpiling or placement on an aeration floor. The third example when using side dump delivery trucks, have trucks unload manure in a long low windrow, and then place the amendment in another long low windrow alongside about 22 feet apart, then use a side discharge windrow turner with a spray bar to apply wastewater to combine and then mix the windrows together using the turner in 2 passes. Large loaders move about 500 cubic yards per hour, compost turners move over 4000 cubic yards per hour. So each touch is cheaper per unit.

Future Plans

Phases two and three are under development to move the entire windrow operation from Meridian Idaho to the new site within 2 years.

Authors

Presenting authors

-

- Jeffrey Gage, Director of Consulting, Green Mountain Technologies, Inc.

- Mike Murgoitio, President, Timber Creek Recycling

- Caleb Lakey, Vice President, Timber Creek Recycling, LLC

Corresponding author

Jeffrey Gage, Director of Consulting, Green Mountain Technologies, Inc., jeff@compostingtechnology.com

Additional author

Caleb Lakey, Vice President, Timber Creek Recycling, LLC.

Additional Information

-

- https://www.compostingtechnology.com

- https://www.timbercreekrecycling.com/

- Citations

- Industrial Composting: Environmental Engineering and Facilities Management, Eliot Epstein, CRC Press, 2011. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.1201/b10726/industrial-composting-eliot-epstein?_ga=2.37894116.67590306.1739841108-1296093157.1739841108

- Compost Science & Utilization https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/ucsu20

- Biocycle Magazine https://www.biocycle.net/

- Case Studies: Annen Brothers, Mt Angel, OR. Timber Creek Recycling, Meridian and Nampa, ID. Stage Gulch Organics Compost Facility, Sonoma, CA.

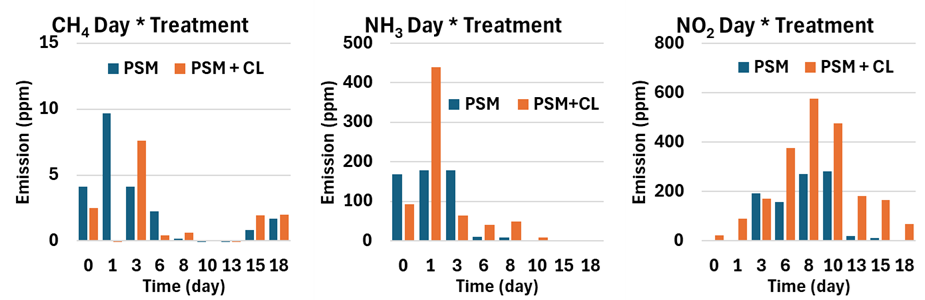

We are developing a ground-based, mobile measurement approach where manure storage systems are circled with a backpack methane gas analyzer and measurements are integrated with on-site wind measurements to calculate emission flux rates. Twelve commercial dairy farm manure storage systems, representing a range of herd sizes and pre-storage manure treatments are collaborating on the research. Once per month, each manure storage structure at each site is circled 10 consecutive times with a methane gas analyzer. A drone equipped with a separate methane analyzer is also used to verify ground-based measurements amidst the methane plumes. Divergence (Gauss’s) theorem is then applied to concentration measurements and anemometer wind data to estimate the net rate of methane flux. These observed methane emission fluxes are compared to International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) modeled emissions as well as state inventories.

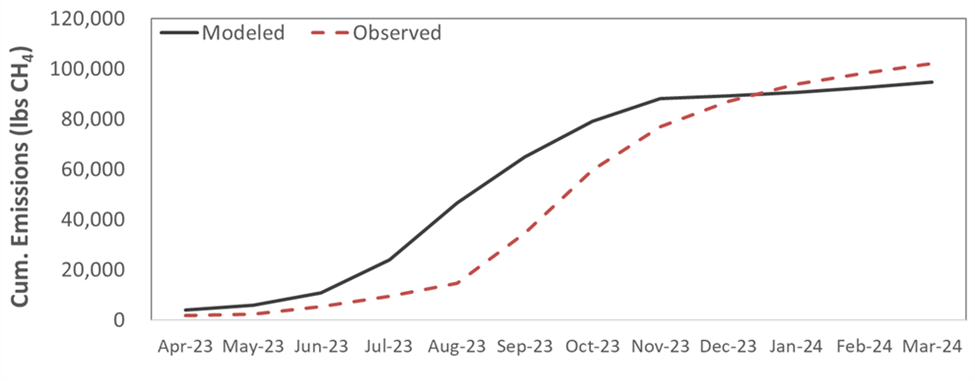

We are developing a ground-based, mobile measurement approach where manure storage systems are circled with a backpack methane gas analyzer and measurements are integrated with on-site wind measurements to calculate emission flux rates. Twelve commercial dairy farm manure storage systems, representing a range of herd sizes and pre-storage manure treatments are collaborating on the research. Once per month, each manure storage structure at each site is circled 10 consecutive times with a methane gas analyzer. A drone equipped with a separate methane analyzer is also used to verify ground-based measurements amidst the methane plumes. Divergence (Gauss’s) theorem is then applied to concentration measurements and anemometer wind data to estimate the net rate of methane flux. These observed methane emission fluxes are compared to International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) modeled emissions as well as state inventories. We find that this methodology provides a reliable, cost-effective way to estimate methane emissions from manure storages. Observed emissions track modeled emissions with similar magnitudes, though models may be overestimating emissions during the growing season and underestimating during the winter months in this region (Figure 1). While emissions patterns are generally similar for each of the farm sites, with some farms and some individual monthly observational estimates there can be substantial deviation from predicted emission rates.

We find that this methodology provides a reliable, cost-effective way to estimate methane emissions from manure storages. Observed emissions track modeled emissions with similar magnitudes, though models may be overestimating emissions during the growing season and underestimating during the winter months in this region (Figure 1). While emissions patterns are generally similar for each of the farm sites, with some farms and some individual monthly observational estimates there can be substantial deviation from predicted emission rates.