Why Consider Small or Medium Digester Projects?

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is an environmentally-friendly manure management process that can generate renewable energy and heat, mitigate odors, and create sustainable by-products such as bedding or fertilizer for dairies and farmers. However, due to economics, a majority of commercially available AD technologies have been implemented on large farming operations. Since the average herd size of dairies across the country is below 200 head of milking cows, there is a need for small-scale AD systems to serve this market.

What did we do?

What did we do?

The University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, in collaboration with BIOFerm™ Energy Systems, installed the EUCOlino—a small-scale, mixed, plug-flow digester—onto on a 136 milking head Wisconsin Dairy. The system is pre-manufactured, containerized and requires very limited on-site construction. This includes grading, pouring a concrete pad for the containers and electrical services installation.

Start-up and commissioning were performed after the delivery of the 64 kWe combined heat and power (CHP). The input materials consist of bedded-pack dairy manure (corn or bean stover and straw), parlor wash water, and minor additional substrates such as lactose or fats, oils, and grease.

Solid materials are dumped via bucket tractor into a hopper feeder system that uses an auger to feed substrate into the anaerobic digestion tank. Additional parlor water is piped directly into the anaerobic digestion tank and mixed with the solids to make a feedstock of approximately 13% total solids. The solids are fed hourly, which is controlled by the PLC system.

The digester has a ~30-day retention time and the biogas produced is stored in a bag above the fermenters. Biogas produced is conditioned and combusted in a CHP mounted on a separate skid. Effluent from the system is pumped directly to an open pit lagoon for storage and subsequently land applied as fertilizer. The system produces approximately 25 – 33 m3/hour of biogas, with a raw biogas quality of 52-60% CH4 and less than 700 ppm H2S.

|

|

|

What have we learned?

This project has been an important step forward in developing future small-scale anaerobic digesters across the U.S. Notably, our installation has given us insight into balancing system economics with the size of small-scale models; the energy output of the system must exceed pre-processing energy requirements and the digester must still be large enough for the designed residence time. Our experience has shown that, while reducing the size of a digester, these requirements remain essential for an installation to economically make sense.

Additionally, challenges involved in AD at the small-scale are related to pre-processing or feedstock conveyance. Once suitable consistence or size for conveyance, anaerobically digesting the organic fraction can be relatively easy. Inconsistency of incoming feedstocks is very detrimental to the system’s stability. Additionally, exterior feedstock storage and above ground piping can limit processing potential when severe cold weather settles in. While all of these are challenges that are easily overcome with engineering, they come at a cost and that can make or break the economics at this scale.

Future Plans

For the small-scale EUCOlino to be effective in the United States, it is key to establishing a U.S.- based manufacturing location. Pre-processing needs to be well-suited to the incoming feedstock. Post-digestion products need established off-takers, for electricity generation, bedding, fertilizer, etc.

Authors

Steven Sell, Manager Application Engineer, BIOFerm™ Energy Systems beaw@biofermenergy.com

Whitney Beadle, Marketing Communications, BIOFerm™ Energy Systems

Additional information

The following publications offer additional information on the Allen Farms digester:

- American Dairymen: BIOFerm Energy Systems Offers Dairy Producers Cutting Edge Digestion Biogas Technology

- Progressive Dairymen: Oshkosh Paves Way for Small-Scale Digester Projects

- BioCycle: Modular Dairy Digester

- North American Clean Energy: Energy Systems & Allen Farms Awarded Grant to Fund Feasibility Study

- University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh: University of Wisconsin Oshkosh—Titan 64 (Small Farm Biogas System—EUCOlino)

Readers interested in this topic can also visit our website for more information on the Allen Farms digester and other BIOFerm projects. We can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2015. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Seattle, WA. March 31-April 3, 2015. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

What did we do?

What did we do?

What did we do?

What did we do?

Future Plans

Future Plans

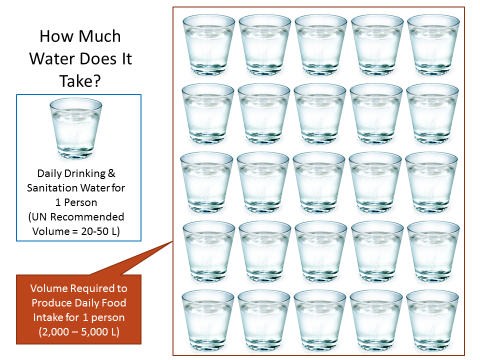

The realization of these interdependencies, and more importantly, the fragility of the balance of satisfying these needs must lead us to proactively invest in agricultural innovations, as much as we have with water and energy. The needs for energy innovations have been wildly popularized in society, such as may be seen through promulgation of solar panels the world-over. Similarly, water sustainability innovations, such as reclaiming water from wastes, water conservation devices, and even desalinization. However, the drive for innovations in maximizing the productivity of healthy foods through sustainable agricultural practices seems, by many, silent in comparison.

The realization of these interdependencies, and more importantly, the fragility of the balance of satisfying these needs must lead us to proactively invest in agricultural innovations, as much as we have with water and energy. The needs for energy innovations have been wildly popularized in society, such as may be seen through promulgation of solar panels the world-over. Similarly, water sustainability innovations, such as reclaiming water from wastes, water conservation devices, and even desalinization. However, the drive for innovations in maximizing the productivity of healthy foods through sustainable agricultural practices seems, by many, silent in comparison.