With proper planning, manure management can be beneficial to both the farm and the environment. This article provides information on environmental and health impacts of manure as well as proper manure storage and management.

J.G. Davis, A. M. Swinker, and Crystal Smith

Introduction

Manure management is a vital part of modern day horse ownership. Many horses spend a significant portion of their day in stalls, accumulating large amounts of manure and stall waste. Horse owners generally have a limited amount of time to spend caring for their equine charges; thus, efficient manure removal and disposal is crucial. Additionally, horse facilities are often managed on relatively small acreage, limiting manure storage and application options.

The intent of this publication is to educate horse owners on the effective management of horse manure. Horse owners will first gain a thorough understanding of the quantity and characteristics of manure produced by horses. Finally, on-site options for handling, storing and treating manure will be discussed, keeping in mind sound facility management and environmental stewardship.

Managing horse manure can be a complex topic, and the principles presented here should be tailored to your specific situation. Please contact your local extension agent or natural resources conservation service field office for technical support.

Horse Manure Production and Characteristics

Horses produce large amounts of manure. In fact, if the manure produced from one horse were allowed to pile up in a 12-foot-by-12-foot box stall for one year, it would accumulate to a height of 6 feet. On any given day, the average 1,000-pound horse will produce approximately 50 pounds of manure. This amounts to about 8.5 tons per year.

Manure is not the only material being removed when stalls are cleaned. Wet and soiled bedding material must also be removed and can equal almost twice the volume of the manure itself. The amount of bedding material removed will vary by type — shavings, sawdust, straw — but on average, totals between 8 and 15 pounds. Total stall waste produced averages between 60 and 70 pounds per day, which amounts to approximately 12 tons of stall waste per year.

When managed properly, horse manure can be a valuable resource. Manure is a source of nutrients for pasture production and can be utilized as part of a pasture management strategy to improve soil quality. The fertilizer value of the 8.5 tons of manure produced annually from a 1,000-pound horse can amount to 102 pounds of nitrogen (N), 43 pounds of phosphorous (P2O5) and 77 pounds of potash (K2O). Nutrient values for manure vary widely. The type and quantity of bedding material included also affects the overall fertilizer value. If a more accurate measure of nutrient content is needed, contact your local cooperative extension office for a list of laboratories that perform manure analysis.

Environmental and Health Impacts

Many horse owners do not have enough land or vegetative cover to properly apply large amounts of manure and nutrients. If not managed properly, manure can deposit excess nutrients into the environment via surface runoff or as a leachate, or water-contaminated with manure, from improper manure storage and land application. This can negatively impact water quality and subject landowners to investigation, and in some cases, legal action under an Agricultural Stewardship Act. For these reasons, horse operations are encouraged to use best management practices and develop a nutrient management plan. Nutrient management plans describe the farm’s manure production, soil fertility and recommended manure application and removal rates. For more information on designing a plan specific to your farm’s needs or identifying other conservation resources, contact your local cooperative extension office.

Internal parasites, insects, rodents and odors can be manure-related health concerns on horse farms. These issues can be minimized through carefully planned manure storage and handling. Internal parasites may be found in horse manure and can compromise the health and welfare of the horses stabled or grazing the land. Composting manure and properly timed land application can limit the risk of parasite exposure. Insects, especially flies, become a nuisance on farms where stockpiled manure serves as fly larvae habitat. Flies breed when spring temperatures rise above 65-degrees F. Flies deposit their eggs in the top few inches of moist manure, and these eggs can hatch in as little as seven days under optimal temperature and moisture conditions. Therefore, fewer flies will develop if you remove manure from the site or make it undesirable for fly breeding through processes such as composting within a maximum seven-day cycle. Naturally occurring fly predators can also be used to limit the fly population at the manure pile but are no replacement for sound management practices. Rodents can be a problem when manure is stockpiled for extended periods of time, providing them with a warm, safe environment. Additionally, nuisance odor from manure piles can result in strained relationships with neighbors. Composting or timely removal of manure piles will help keep odors to a minimum. Finally, keep in mind that large piles of manure are not aesthetically pleasing to your neighbors or those visiting your farm. Keeping the manure storage site screened with vegetation or fencing or by location will help to enhance the beauty of your farm.

Horse Manure Storage and Utilization

The average horse produces between 60 and 70 pounds of stall waste per day. Multiply this by several horses, and it is easy to see the importance of having methods in place to manage the manure produced on a daily basis. Letting manure pile up in stalls and paddock areas leads to a host of problems. It is not only unhealthy for your horse — inviting for pests and odors — and aesthetically unpleasing, but the sheer amount of manure produced will overwhelm you. Many handling and storage options exist, but it’s up to you to choose the method that best suits your horse operation.

Horse operations with available land may choose to apply stall waste to pastures as fertilizer. This should be done based on soil-test results and nutrient needs. A soil analysis is needed to determine the fertility needs of a pasture. Soil analysis is provided through your land-grant university’s soil testing laboratory for agricultural operations, which include horse farms, free of charge. Contact your local cooperative extension office for instructions on how to take a soil sample. There are also private laboratories that offer soil-testing services.

In many situations, manure can be picked directly from the stall, deposited into a manure spreader, applied to the pasture and harrowed into the soil. Barns not constructed with a management scheme allowing for stall access by a manure spreader require manure to be carted from the stall to the manure spreader some distance away. In this case, ramps or dropped spreader parking can be helpful to avoid lifting the heavy, cumbersome stall waste. Keep in mind that when spreading manure from stalls bedded with sawdust or shavings, the applied stall waste can stunt plant growth. Wood products contain carbon that soil microbes use for energy but not enough nitrogen to build proteins. The microbes draw nitrogen from the soil to make up for this deficit to such a degree that they can actually limit plant growth. To manage this nitrogen deficiency, nitrogen fertilizer can be applied. Or, to avoid the problem completely, manure can be composted before it is applied to the land.

When direct pasture application is not an option, manure storage facilities become a necessity. The storage facility should be convenient to the barn. A general rule of thumb is to plan for 180 days of long-term manure storage. This allows operations the flexibility to store manure when conditions are not ideal for manure application, as when fields are frozen or wet. This storage area should be accessible to the equipment that will ultimately remove the accumulated stall waste. Manure storage facilities should also be downwind and screened from nearby homes to avoid potential complaints about odors and aesthetics. The size, type and location of manure storage facilities will vary by horse operation based on the amount of manure produced, length of time the manure will be stored and available land area. Always be sure to contact your local authorities regarding zoning regulations and additional restrictions.

Minimum separation distances commonly recommended for composting and manure-handling activities. Source: On-Farm Composting Handbook, NRAES-54

| Sensitive Area |

Minimum Seperation Distance (feet) |

| Property Line |

50-100 |

| Residence or place of business |

200-500 |

| Private well or other potable water source |

100-200 |

| Wetlands or surface water (streams, ponds, lakes) |

100-200 |

| Subsurface drainage pipe or drainage ditch discharging to a natural water source |

25 |

| Water Table (seasonal high) |

2-5 |

| Bedrock |

2-5 |

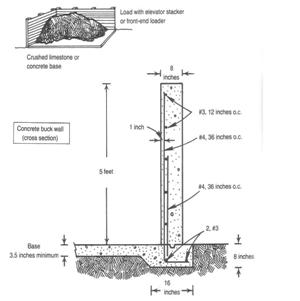

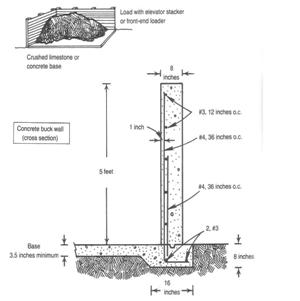

Manure Storage Construction

Manure storage should be designed to limit the chance of leachate entering surface and groundwater resources. Ideally, storage piles should be placed on gravel, hardened clay or concrete pads that slope inward. The construction of manure storage sites will vary, based on individual situations and soil types. For instance, concrete pads may be necessary in areas with sandy soils where contaminants are more likely to reach groundwater. Storage piles should not be placed in low-lying or flood-prone areas, and care should be taken to direct water from higher elevations away from the site. The natural resources conservation service or local soil and water conservation district offices can provide individualized manure storage design specifications.

Composting

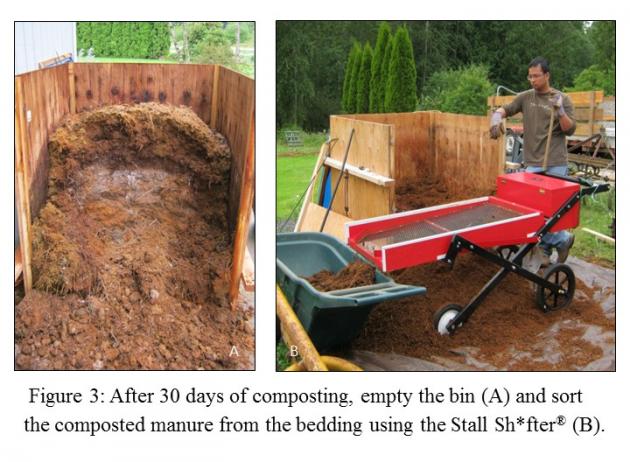

Composting horse manure is relatively simple but does involve more than simply piling the water. While many farms stockpile their manure, few truly compost. Composting is essentially managed decomposition. Managing the process can virtually eliminate odor, flies, weed seeds and internal parasites found in horse manure and create a valuable soil amendment for resale or for pasture application. To manage a compost pile, the following factors must be taken into consideration: carbon to nitrogen ratio, oxygen, moisture and temperature.

Compost Pile

The microorganisms found in compost are most active when their diet contains about 30 times more carbon than nitrogen, or a C:N ratio of 30:10. Horse manure’s C:N ratio is typically 40:1 due to the large amounts of bedding mixed with it but generally doesn’t require additional nitrogen provided it has enough moisture and oxygen.

Composting is an aerobic process, that is, it requires oxygen. If a compost pile doesn’t get enough oxygen, these anaerobic conditions can result in unpleasant odors, such as those normally associated with stockpiling manure, and slowed decomposition. There are several ways to provide oxygen to a compost pile. The most common way is to turn the pile. For large piles or windrows, turning is generally done using the bucket of a tractor or front-end loader. For smaller piles, a pitchfork will certainly get the job done; but for these operations, you may want to consider using an aerated, static-pile design, which doesn’t require turning.

Typical horse-stall waste tends to be dry and will need added moisture to create the ideal conditions for compost microbes. The moisture content should be about 50 percent, or roughly the consistency of a wrung-out sponge. If rainfall does not provide enough additional moisture, the pile may need to be watered periodically. On the other hand, too much water can also be detrimental, displacing oxygen inside the pile and causing anaerobic conditions. If environmental conditions such as rain or snow are providing too much water, the pile may need to be covered. Some compost-storage designs call for permanent roofs, but properly anchored plastic tarps can be just as effective.

Compost Trouble Shooting

| Problem |

Possible Cause |

Remedy |

| Fresh manure, but pile won’t heat up. |

The pile is: 1) too dry,

2) too wet; and/or

3) Outside temp is too cold. |

1) Add water evenly to pile.

2) Aerate and cover.

3) Wait for warmer temps and turn as needed. |

| Pile was hot, but now temps are falling. |

1) Pile is settling.

2) Moisture is less than 50 percent. |

1) Turn pile; and/or

2) Add water evenly to pile. |

| Pile is more than 160-degrees F and has gray ash-like mold. |

Pile is too dry. |

Add water evenly to pile. |

| Pile has gone through two or more heat cycles but still has some material that has not decomposed. |

Wood shavings decompose slowly. |

Ensure pile has proper moisture content, add water if needed. |

| Pile emits bad odor. |

Pile is too wet and has become anaerobic inside. |

Turn to aerate and increase water evaporation, apply cover to limit additional rainwater. |

* Table does not include all scenarios, see resources/references for more in-depth publications on the subject.

One of the best ways to monitor your compost pile is by using a thermometer. Compost thermometers should have a probe at least 36 inches long and are available through many garden supply stores. The goal is to have sustained temperatures of 130- to 150-degrees F in the pile interior. This will optimize decomposition and also kill pathogens and weeds.

Compost-pile design and storage facilities will depend on the size of the operation and the equipment available. For a farm with two to six horses, small static piles, which use perforated PVC pipes to draw in air and don’t require turning, may be ideal. While not necessary, the use of multiple bins can allow separation of distinct batches. In this situation, horse manure should be piled approximately 5 to 8 feet high with a base that is two times the width and length of the height. For example, a 10-foot by 10-foot bin could accommodate a pile that is 5 feet high. PVC pipes should be placed after the pile is about 1 foot high so that the ends remain visible as more manure is added.

For larger farms with access to bucket loaders, manure spreaders and/or specialized composting equipment, larger piles or windrows may be the most efficient design options. These piles may be slightly larger in height and width and considerably longer but will require periodic tuning.

Example of mixing / storage area with buckwall

Compost will decompose more efficiently if the mix is uniform. Starting with a uniform mix is even more important in the case of static piles, since they will not be turned during the decomposition process. Some farms utilize a temporary storage and mixing area to aid in this process.

Benefits of Composting

- Creates valuable soil amendment

- Stabilizes nitrogen into a slow release form

- Avoids the problem of nitrogen immobilization

- Reduces manure volume by 50 percent

- Destroys weed seeds, fly larvae and internal parasites

- Eliminates or reduces the cost of off-site disposal

Conclusion

With careful planning, proper manure management not only protects the environment and increases the efficiency and aesthetics of your farm, but might also save you money while enhancing your pastures. The following resources provide more information on composting and additional facility design specifications.

Field Guide to On-Farm Composting and the On-Farm Composting Handbook, available from the Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service(NRAES) at www.NRAES.org.

Horse Facilities Handbook, available from the MidWest Plan Service at www.mwpshq.org.

Check out your local university’s agronomy handbook containing information on soil production, soil sampling, nutrient management, utilization of organic waste and more.

Purpose

Purpose