Purpose

The on-farm disposal of swine carcasses poses a potential risk to groundwater quality due to the generation of leachate with nitrate compounds (Koh et al., 2019). This study aims to evaluate the vertical movement of nitrate nitrogen from leachate produced during decomposition of swine carcasses in Nebraska soil types by integrating HYDRUS-1D modeling with GIS-based spatial analysis.

What Did We Do?

Leachate from six on-farm mortality disposal units was gathered during a year-long field study. A soil column study was conducted using the leachate from the field study to evaluate contaminant fate and transport through two common Nebraska soil types – a sandy clay loam and a silty clay.

HYDRUS-1D Model Calibration and Simulation. The model was calibrated using laboratory soil column data; no field-scale observations were used for validation. The objective was to parameterize the model based on controlled experimental conditions and use these simulations to inform spatial risk assessments.

Soil Hydraulic and Solute Transport Parameters. The van Genuchten-Mualem model was chosen to define the soil hydraulic properties for the two soil types used in the columns study, sandy clay loam (SCL) and silty clay (SC). Ten simulations were conducted to develop the HYDRUS-1D model, each run for 365 days, using the mean monthly nitrogen (N lb/ac) generated in leachate during the field study, which was converted into NO₃-N units. The model simulated nitrate leaching in a 10-meter soil column profile using boundary conditions that replicated laboratory leachate transport where the upper boundary represents a constant flux boundary to simulate leachate application based on controlled experimental data and lower boundary represents a free drainage condition representing natural percolation.

Model Calibration. Calibration was performed using inverse modeling within HYDRUS-1D, adjusting key parameters to minimize the sum of squared errors (SSQ) between observed and simulated nitrate concentrations in soil columns at 5 cm, 15 cm, and 25 cm. The results may not fully represent field-scale variability since the model was calibrated only using laboratory data. However, the controlled conditions ensured that parameterization was optimized for subsequent spatial risk assessment using GIS. The sandy clay loam soil strongly correlated with observed and simulated values (R²=0.99). The silty clay soil had a slightly lower R² (0.86). Identical RMSEs of 3.15 for both soil types suggest similar levels of overall deviation from observed concentrations.

The model outputs were exported as time-series CSV data and georeferenced to the study area using ArcGIS Pro. Statewide soil texture data were obtained from the USDA-NRCS soil texture class map (Knoben, 2021) and depth were derived from interpolated data using the Kriging method, based on historical water levels from the UNL Groundwater and Geology Portal (CSD, 2025) respectively. Soil type, groundwater depths, and digital elevation models (DEM) were imported into ArcGIS Pro and processed under the NAD 1983 UTM Zone 14N coordinate system to ensure spatial alignment.

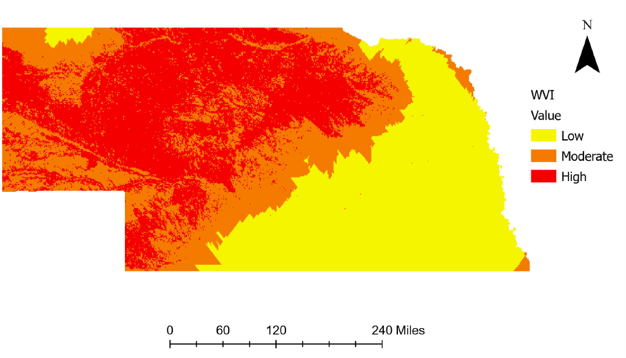

Hydraulic parameters for the ten soil textural classes in Nebraska were defined by the ROSETTA model in HYDRUS-1D and used to model nitrate transport and concentration at 2m soil depth at 1,000 randomly defined locations statewide. Nitrate concentration data at 2 m of soil depth was interpolated using the Kriging tool to create a continuous nitrate concentration data layer. Soil type and groundwater depth data were converted into raster format to enhance the spatial analysis, and a vulnerability assessment was performed using a classification system based on soil permeability, groundwater depth, and nitrate concentrations to produce a spatial representation of groundwater contamination vulnerability (Figure 1).

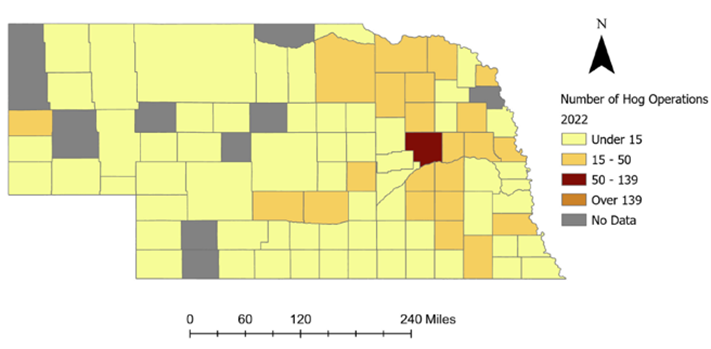

Swine population inventories (Figure 2) were obtained from the 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture (IARN, 2025), allowing for comparison of county-level swine populations to groundwater contamination vulnerability.

What Have We Learned?

The HYDRUS-1D model successfully modeled nitrate movement in the soil profile, producing time-series data that matched expected trends based on soil properties and environmental conditions. Counties with the greatest groundwater contamination risk are predominantly located in the western and northern regions of the state due to well-drained soils and shallow depths of groundwater. Very few swine operations are located in these moderate- to high- risk zones, but those that are located in these zones should be aware of the potential for groundwater contamination and should utilize mortality disposal methods that minimize leachate production. Four counties in northeast Nebraska contain moderate swine populations and have moderate to high risks for groundwater contamination. Castro and Schmidt (2023) found that carcass disposal via shallow burial with carbon (SBC) yielded much less leachate – and, subsequently, much lower loads of contaminants to the soil environment – than composting of whole or ground swine carcasses, suggesting that SBC may be a more environmentally conscious disposal method in these counties. Counties having low vulnerability to groundwater contamination cover much of the state’s central and eastern portions where the majority of swine production is located. This study provides critical insights into the risks of groundwater contamination from on-farm swine carcass disposal in Nebraska. Guidance for on-farm disposal of mortalities by all livestock producers should focus on selecting disposal methods that minimize leachate production and contaminant transport potential.

Future Plans:

Outreach efforts will focus on promoting mortality disposal BMPs with a primary focus on selecting disposal methods that minimize leachate production. Field research will be expanded to include evaluation of multiple carbon sources used for on-farm carcass disposal to reduce leachate generation. Future research will focus on enhancing the predictive accuracy of the HYDRUS-1D model by incorporating field-scale validation using observed nitrate concentrations from groundwater monitoring wells in high-risk areas. This validation will improve the reliability of the model’s output and support more precise risk assessments.

Authors:

Presenting Author

Gustavo Castro Garcia, Graduate Extension & Research Assistant, Department of Biological Systems Engineering, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Corresponding Author

Amy Millmier Schmidt, Professor, Department of Biological Systems Engineering and Department of Animal Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, aschmidt@unl.edu

Additional Authors

Mara Zelt, Research Technologist, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Aaron Daigh, Associate Professor, Department of Biological Systems Engineering and Department of Agronomy & Horticulture, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Benny Mote, Associate Professor, Department of Animal Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Carolina Córdova, Assistant Professor, Department of Agronomy & Horticulture, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Pork Board Award #22-073. The authors wish to recognize Jillian Bailey, Logan Hafer, Alexis Samson, Nafisa Lubna, Andrew Ortiz, and Maria Oviedo Ventura, for their technical assistance during the field and column studies that provided input data for this modeling effort.

Additional Information

Castro, G., and Schmidt, A. (2023). Evaluation of swine carcass disposal through composting and shallow burial with carbon (poster presentation). ASABE AIM. Omaha, NE. July 9 – 12, 2003.

CSD. (2025). UNL Ground Water and Geology Portal: CSD Ground Water and Geology Data Portal. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved from: CSD Ground Water and Geology Data Portal.

IANR. (2025). Hogs and pigs, operations with inventory, total operations by county. Nebraska Map Room. Data source: Census of Agriculture, 2022. Retrieved from: https://cares.page.link/Xu1J.

Knoben, W. J. M. (2021). Global USDA-NRCS soil texture class map, HydroShare, https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.1361509511e44adfba814f6950c6e742.

Koh, EH., Kaown, D., Kim, HJ., Lee, KK., Kim, H., and Park, S. (2019). Nationwide groundwater monitoring around infectious-disease-caused livestock mortality burials in Korea: superimposed influence of animal leachate on pre-existing anthropogenic pollution. Environ Int 129:376–388.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.