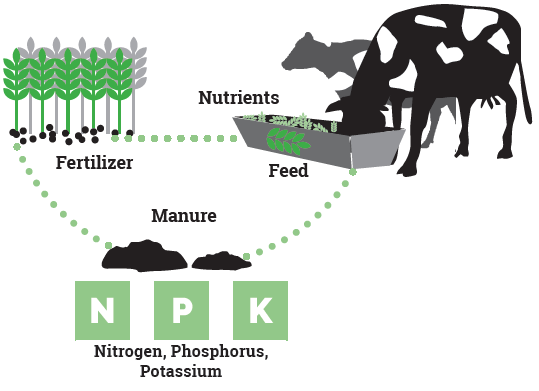

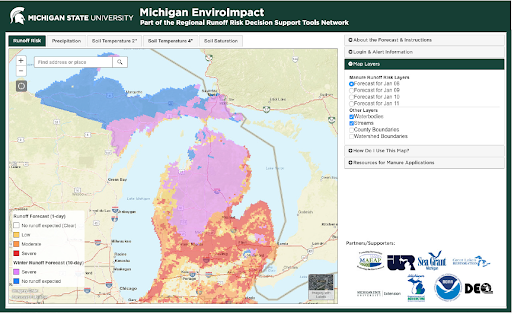

The purpose of the MI EnviroImpact Tool is to provide farmers with a daily runoff risk decision support tool that can aid in effectively planning short-term manure and nutrient application. This not only helps keep nutrients on the field and potentially saves money, but it also helps to protect our waterways in Michigan.

What did we do?

Farmer interest groups were pulled together for initial piloting and testing of the MI EnviroImpact tool to hear what worked and what needed improvement. The goal was to make this a very user-friendly tool that everyone could use. Additionally, educational and outreach materials were created (factsheet, postcard, YouTube videos, and presentations) to help get the word out about this decision support tool. The ultimate goal of the MI EnviroImpact tool is for use as a decision support tool for short-term manure and nutrient application. The tool derives the runoff risk forecast from real-time precipitation and temperature forecasts. This information is then combined with snow melt, soil moisture and temperature, and other landscape characteristics to forecast times when the risk of runoff will be higher. The MI EnviroImpact tool is applicable in all seasons and has a winter mode for times when the average daily snow depth is greater than 1 inch or the 3-day average soil temperature (top 2 inches) is below freezing.

What did we learn?

Through our work with the MI EnviroImpact Tool and those that helped to develop this tool, we were able to spread awareness of this user-friendly tool, so that more farmers would be likely to use it to help in nutrient application planning. Furthermore, those outside of the farming community have been very encouraged to see that agriculture is continuing to take steps in being environmentally friendly. Additionally, others have viewed this tool as a resource outside of farmers, showing that the MI EnviroImpact Tool has broader implications than just agriculture.

Future Plans

Future plans include continuing education about the MI EnviroImpact Tool as well as continued distribution of educational materials to help spread awareness of the tool itself.

Additional Information

Those who would like to learn more about the MI EnviroImpact Tool can visit the following links:

- The MI EnviroImpact Tool

- The MI EnviroImpact Tool Factsheet

- MI EnviroImpact Tool: Managing Manure Application

- MI EnviroImpact Tool: User’s Guide

- Manure Application Planning with the MI EnviroImpact Tool

- Free webinar: Nutrient application planning with the Michigan EnviroImpact Tool

- Michigan releases new nutrient management tool

Acknowledgements

This project was prepared by MSU under award NA14OAR4170070 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

MSU is an affirmative-action, equal-opportunity employer, committed to achieving excellence through a diverse workforce and inclusive culture that encourages all people to reach their full potential. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, gender identity, religion, age, height, weight, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status, family status or veteran status. Issued in furtherance of MSU Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Jeff Dwyer, Director, MSU Extension, East Lansing, MI 48824. This information is for educational purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names does not imply endorsement by MSU Extension or bias against those not mentioned.

Project Collaborators:

Heather A. Triezenberg, Ph.D.

Extension Specialist and Program Leader, Michigan Sea Grant

Michigan State University Extension

Community, Food and Environment Institute

Fisheries and Wildlife Department

Meaghan Gass

Sea Grant Extension Educator

Michigan State University Extension

Jason Piwarski

GIS Specialist

Michigan State University

Institute of Water Research

Dustin Goering

Senior Hydrologist

North Central River Forecast Center

NOAA National Weather Service

Cindy Hudson

Communications Manager, Michigan Sea Grant

Community, Food & Environment Institute

Michigan State University Extension

Jeremiah Asher

Assistant Director

Institute of Water Research

Michigan State University

Kraig Ehm

Multimedia Producer

ANR Communications and Marketing

College of Agriculture and Natural Resources

Michigan State University

Luke E. Reese

PhD, Associate Professor

Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering

Michigan State University

Marilyn L. Thelen

Associate Director, Agriculture and Agribusiness Institute

Michigan State University Extension

Todd Marsee

Senior Graphic Designer

Michigan Sea Grant

University of Michigan

Mindy Tape

Manager

ANR Communications & Marketing

Michigan State University Extension

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2019. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Minneapolis, MN. April 22-26, 2019. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.