Purpose

Backyard poultry production is growing globally with 85 million backyard chickens estimated in the U.S. (Mace & Knight, 2024). Whether kept as pets or to provide a local and sustainable food source, flocks can harbor pathogens and antibiotic-resistant bacteria that can be transmitted to humans via the environment, pests, food products, and direct contact. Poultry waste can contaminate soil and water sources, posing risks to nearby humans and other animals. Flocks can attract pests that may carry diseases and disrupt local ecosystems. This project, which will launch in the summer of 2025, aims to improve understanding among backyard poultry farmers of potential health, environmental, community, and food safety risks associated with their systems and motivate the adoption and promotion of behaviors critical to public health and sustainability of local food systems using a peer-to-peer outreach approach.

This project will evaluate an approach to motivating behavioral changes among a cohort of backyard poultry farmers that is predicated on evaluating current flock management practices among participants, improving understanding of health risks associated with current practices, and motivating implementation of recommended practices to mitigate health risks. Beneficiaries of project outcomes include members of households in which chickens are maintained, local community members, consumers of local poultry products, and the broader population that shares environmental resources with these sites and are impacted by human health threats. Our project will uniquely address multiple facets of backyard poultry production that contribute to human health, environmental sustainability, food safety, and community well-being through engagement with existing poultry owners to improve knowledge, promote the adoption of best practices, and facilitate communication networks. Assessments of current production practices among participating local backyard poultry farmers will inform educational needs related to managing these systems for environmental and public health benefits. Facilitated engagement among participants during educational events will promote shared goals, motivate practice adoption, and build confidence among participants in their role as citizen scientists capable of promoting a broader community understanding of the topics addressed.

What Did We Do?

The overall goal of this project is to mitigate potential disease transmission risks to humans from small poultry flocks by delivering data-informed educational programming and assessing subsequent behavioral changes among audience members. After a thorough investigation using previous studies conducted on the impact of community engagement in health education, we have designed our research to identify, deliver, and assess an effective methodology to achieve the following objectives.

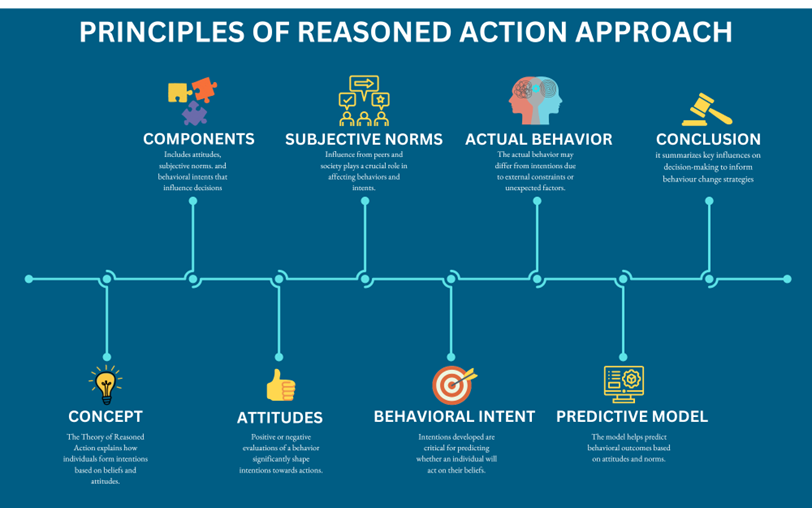

Objective 1: Evaluate the knowledge, perceptions, and practices among backyard poultry farmers that may contribute to their risks for acquiring AMR genes/infections from their birds using a Reasoned Action Approach.

Objective 2: Quantify the contribution of backyard poultry manure and bird management practices to the presence and concentration of pathogenic organisms and resistance genes in the environment via sampling and analysis of manure, soils, runoff, and flying insects.

Objective 3: Develop, deliver, and assess impacts of educational programming designed to motivate the adoption of new integrated antimicrobial management approaches in backyard poultry farming to reduce the potential spread of AMR.

Thirty backyard poultry farmers from up to three counties in Nebraska will be recruited through community groups, personal connections, and university extension contacts. Participants will be surveyed and observed to understand their current knowledge, perceptions, and management practices, and identify knowledge gaps related to bird health, biosecurity, and disease transmission risks. The Reasoned Action Approach, a social cognitive model for behavioral analysis will be used to categorize the data, predicting and explaining their behavior towards healthy farming practices. The mixed-methods study will use standard statistical methods and qualitative data for a richer interpretation.

Sampling of environmental matrices and potential insect transmission vectors will be conducted and used to complete a risk factor assessment to understand disease demography.

Through face-to-face and digital sessions, engagement and education sessions will be designed to address knowledge gaps in poultry handling, waste management, personal hygiene, water quality, food safety, and human health risks. It will promote best practices and encourage participation through rewards, project-based learning, on-farm demonstrations, and regular reflection on personal impact. The recruited farmers will be appointed as trainers for other farmers in their locality to continue to promote the learning outcomes from the training. The training sessions will be assessed through a post-training survey using a knowledge-based questionnaire, and all discussions with farmers will be recorded for future evaluation. This data will help determine improvements for future outreach events on infectious disease control in backyard poultry farms, enhancing the training’s impact.

What Have We Learned?

The number of households engaging in “backyard poultry production” is growing regionally, nationally, and globally. Evidence also suggests that chickens are not strictly confined to the outdoors but are becoming indoor “pets,” creating complex human-chicken relationships responsible for zoonotic disease outbreaks and antibiotic resistance risks (Singh et al., 2018; Tobin et al., 2015). According to a 2010 study, the USDA confirmed almost 50% of the population related to backyard poultry production lacks knowledge about human health risks associated with contact with live birds (USDA, 2011). Studies reflect a critical need for decision-making support to ensure healthy birds, applying biosecurity practices that mitigate animal-to-human disease transmission risks and development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, promoting environmental sustainability, and providing healthy local food sources to communities. While these systems represent only a small part of the U.S. poultry industry, their positive impact on local food systems is widely recognized, as are their potential contributions to zoonotic disease transmission, antibiotic resistance, and local ecosystem disruptions. Public awareness about poultry-associated health risks and adopting best practices for biosecurity and disease prevention is critical to balancing healthy local food production with community well-being.

Future Plans

This project aims to improve the health, prosperity, and sustainability of backyard poultry farmers by focusing on zoonotic disease transmission, pest management, and natural resource protection. It will provide training, technical assistance, and peer support to improve knowledge and adoption of best practices for producing healthy local food sources. This will reduce health risks, decrease healthcare costs, and support market access and profitability among urban farmers. The community-based approach will foster mutually beneficial relationships among producers, communities, and experts, promoting sustainable production practices that prioritize health, community needs, and the environment.

Authors

Presenting author

Nafisa Lubna, Graduate Student, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Corresponding author

Amy Schmidt, Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, aschmidt@unl.edu

Additional author

Mark E. Burbach, Environmental Social Scientist, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Additional Information

Mace, J. L., & Knight, A. (2024). From the backyard to our beds: The spectrum of care, attitudes, relationship types, and welfare in non-commercial chicken care. Animals, 14(2), 288.

Peters, G. J., & Crutzen, R. (2021). The core of behavior change: introducing the Acyclic Behavior Change Diagram to report and analyze interventions.

Singh, S., Chakraborty, D., Altaf, S., Taggar, R. K., Kumar, N., & Kumar, D. (2018). Backyard poultry system: A boon to rural livelihood. International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies, 5(1), 231-236.

Tobin, M. R., Goldshear, J. L., Price, L. B., Graham, J. P., & Leibler, J. H. (2015). A framework to reduce infectious disease risk from urban poultry in the United States. Public Health Reports, 130(4), 380-391.

USDA. (2011). Reference of the health and management of chicken flocks in urban settings in four U.S. cities, 2010. Fort Collins, CO: USDA.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7–11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.