This webinar will explore how the 360Rain autonomous irrigation system is being used as a new tool for manure management. By enabling in-season manure application, 360Rain opens opportunities to better match nitrogen availability with crop uptake, reduce manure storage time (and associated methane emissions), and even provide supplemental irrigation. This presentation was originally broadcast on September 26, 2025. Continue reading “Rethinking Manure Management with 360Rain: Expanding Application Windows and Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency”

Flies, Frass, Feces, and Fields

This webinar will examine how black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) can transform food and agricultural waste into valuable products for both animal feed and soil health. Presenters will discuss large-scale BSFL production, the frass co-product, and how nutrient content can vary based on inputs and processing. This presentation was originally broadcast on August 15, 2025. Continue reading “Flies, Frass, Feces, and Fields”

Manure processing for discharge water quality – technical performance and county perspectives for advancing water quality

This webinar will examine the potential of advanced manure processing systems to treat manure to water quality standards suitable for discharge. It will feature insights from Dane County Land Conservation, including their objectives in supporting system installation, the ownership and operational structure, financial support mechanisms, observed outcomes, and future planning. This presentation was originally broadcast on June 20, 2025. Continue reading “Manure processing for discharge water quality – technical performance and county perspectives for advancing water quality”

Concise Composting

Purpose

Timber Creek Recycling has operated a turned windrow composting operation using manure and food waste processing by-products and green waste for over a decade in Meridian, Idaho. Pressure from suburban encroachment and the availability of increasingly difficult feedstocks that had excessive odor, created the need to move operations from a farm to an industrial site. Land costs were greater, and potential odor impacts would increase in this move. The owner also requested that the number of touches be reduced to minimize the current workload for compost operators. There are some essential operational & design considerations to manage manure composting on a concise footprint and a limited budget. This presentation describes the operation and design considerations that can apply to any composting operation.

What Did We Do?

Green Mountain Technologies considered three different models of concise composting. Radial stacker bunkers, using a central pivot telescopic conveyor to place and cover active compost piles. Also inwardly turned circular aerated piles, which use a side discharge compost turner to turn the compost towards the center of a large circle. Timber Creek Recycling decided to use a narrow profile rectangular shaped turned aerated pile composting approach. This form uses a long concrete aeration floor that allows the owner to build capacity in six phases and increase the operating efficiencies with each additional phase. This approach kept the expansions in line, so that delivery trucks could unload directly in front of the piles and so that side discharge compost turners could be used to mix feedstocks into one side of the pile and move the composting material through different aeration floor capacities and finally to a long collection belt that directly fed a compost screener. This and the aeration floor reduced touches from 12 to 9, compared to non-aerated windrows, and provided a once a week turning frequency, reducing compost, and curing time from 90 to 45 days.

Steps taken to reach this point.

Industrial land was purchased in Nampa, Idaho, permits received and phase one of construction has been completed and operated for over 9 months. The design compacted a 30-acre operational site to a 12-acre operational site with significantly more capacity than the original. Odor reduction steps were taken to reduce the odor of cheese whey waste activated sludge being delivered to the site by using a lime additive during the screw press step at the cheese manufacturer. A small straddle windrow turner was used to mix the delivered feedstocks, and a food waste de-packager was installed to manage out-of-date or off-specification foods.

What Have We Learned?

The use of reversing direction aeration was not necessary when using positive aeration using a cap of wet wood chips or screened compost covers on top of the piles for the first 7 to 10 days. Odors have not been a problem at the new site using forced aeration compared with turned windrows (un-aerated) at the old site. The higher horsepower side discharge conveyor compost turners do not make economic sense just for phase one but will for all three phases. Wastewater collection and reuse is difficult to manage and needs to be incorporated into the mixing and turning process using an underground main and hose reel located at the far end of the aeration pads.

Take home messages

Aeration using blowers and airpipes below a concrete floor can effectively keep composting operations with challenging feedstocks from smelling bad and increase the biological efficiency and throughput. Use of a woody moist bio cover over the top of the pile is essential for the first 7-10 days for these feedstocks.

Force air through a compost pile at least 6 times per hour using on/off timers to control pile temperatures between 125° and 145° F and to keep oxygen above 13% using a rate of 3-5 CFM/cubic yard. Automated temperature feedback controllers make this simpler and more dependable.

Turn and re-water at least 2 times in the first month, either by top irrigation within 30 minutes before turning, or using a hose reel and spray bar connected to the turner (better) or simply turn piles at least 30 minutes after a big rain event.

Piles shrink over time- Double up the piles after 2 weeks and cure with less forced air at 1-2 CFM/cubic yard for an additional 2 weeks.

Adding capacity over time without increasing travel distances requires delivery directly to the initial composting area and collection from the distant piles using conveyors. On-farm generated feedstocks and the composting operations should be placed together as close as possible. Have delivery and storage of outside amendments be alongside your manure or processing waste discharge locations.

Each touch of the material should be limited, and with each touch involving several key feedstock preparation actions while entering a composting system, such as metering materials together in the correct proportions, and mixing thoroughly while watering and delivering into the first composting stage. Examples include building windrows proportionally with loaders and turning and watering with a windrow turner that can apply pond wastewater as it turns. Second example, if a conveyor is used to collect and discharge a manure in a CAFO, add bulking materials prior to the last conveyor and place into an in-line pug mill before stockpiling or placement on an aeration floor. The third example when using side dump delivery trucks, have trucks unload manure in a long low windrow, and then place the amendment in another long low windrow alongside about 22 feet apart, then use a side discharge windrow turner with a spray bar to apply wastewater to combine and then mix the windrows together using the turner in 2 passes. Large loaders move about 500 cubic yards per hour, compost turners move over 4000 cubic yards per hour. So each touch is cheaper per unit.

Future Plans

Phases two and three are under development to move the entire windrow operation from Meridian Idaho to the new site within 2 years.

Authors

Presenting authors

-

- Jeffrey Gage, Director of Consulting, Green Mountain Technologies, Inc.

- Mike Murgoitio, President, Timber Creek Recycling

- Caleb Lakey, Vice President, Timber Creek Recycling, LLC

Corresponding author

Jeffrey Gage, Director of Consulting, Green Mountain Technologies, Inc., jeff@compostingtechnology.com

Additional author

Caleb Lakey, Vice President, Timber Creek Recycling, LLC.

Additional Information

-

- https://www.compostingtechnology.com

- https://www.timbercreekrecycling.com/

- Citations

- Industrial Composting: Environmental Engineering and Facilities Management, Eliot Epstein, CRC Press, 2011. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.1201/b10726/industrial-composting-eliot-epstein?_ga=2.37894116.67590306.1739841108-1296093157.1739841108

- Compost Science & Utilization https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/ucsu20

- Biocycle Magazine https://www.biocycle.net/

- Case Studies: Annen Brothers, Mt Angel, OR. Timber Creek Recycling, Meridian and Nampa, ID. Stage Gulch Organics Compost Facility, Sonoma, CA.

Effect of Swine Manure Nitrification on Mesophilic Anaerobic Digester Performance

Purpose

This study seeks to quantify the impact of swine slurry nitrification on biogas productivity. Ammonia (NH3) is produced during anaerobic digestion of manure and emitted during storage. Ammonia emissions have adverse impacts on swine health and growth, caretaker health, and local air and water quality. Ammonia is also known to inhibit methanogenic activity during anaerobic digestion, reducing methane potential. Thus, reducing ammoniacal nitrogen in digester feedstock can improve digester performance. A novel approach to nitrogen management, developed by a commercial partner, is nitrifying flush water that feeds into the digester. This technology leverages nitrification to suppress NH3 volatilization through using low-pH, highly nitrified substrate to flush the barns. This alternative reduces in-barn NH3 concentration surge during flushing events. In addition, equilibrium between nitrified (oxidized) flush liquid and reduced urine-feces will reduce ammoniacal nitrogen levels in the feed entering the digester. A barn-scale system (17,000 gallons per day capacity) is currently under testing on a NC swine farm that has an anaerobic digester as part of the waste management system (Figure 1). Understanding the impacts of this treatment on anaerobic digestion under controlled conditions under different organic loading rates is needed. This study aimed to quantify impacts of flush water nitrification on biomethane yield (BMY) in swine manure under two different organic loading rates (OLRs).

What Did We Do?

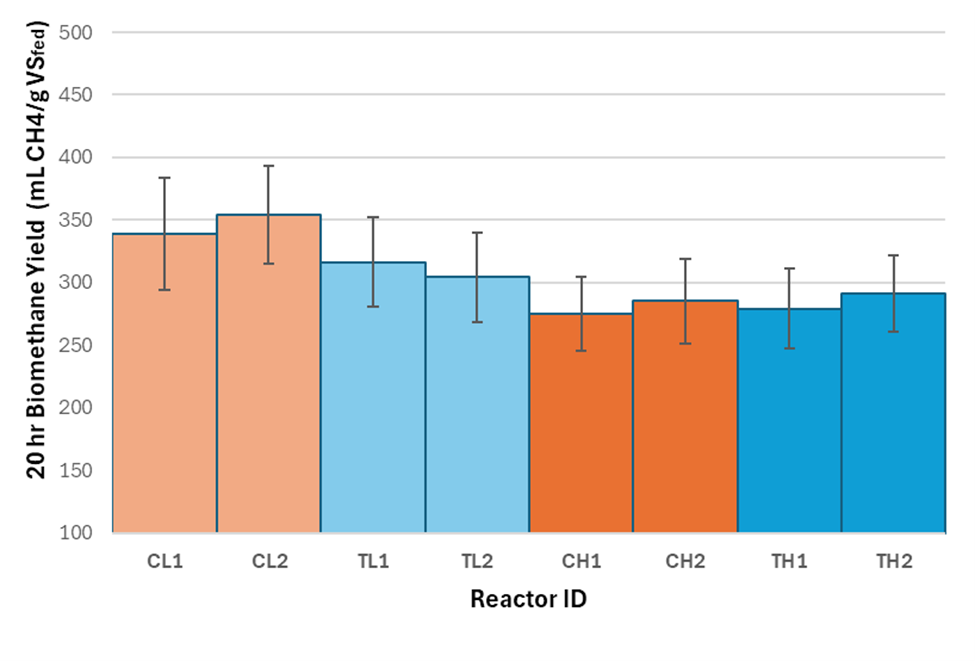

Three different substrates were collected for this study. Substrates were sourced from the same farm every 2 to 3 weeks (Figure 2). Swine slurry was processed through settling > decanting > maceration > screening to create liquid (<1% solids) and solid (>5% solids) fractions needed to formulate desired OLRs. Two OLRs were tested in this study, 1 g VS/L-d (low, L) and 2 g VS/L-d (high, H). For each OLR, two substrate formulations were tested: nitrified (treatment, T) and baseline (control, C). Therefore, four combinations of substrate and OLR were evaluated in this study and were abbreviated as: CH, CL, TH, and TL.

Eight mesophilic reactors at 95°F (35 °C), each with a two-liter active volume, were used to study the impacts of OLR and substrate type, with two replicates per OLR-substrate combination, represented by 1 or 2, respectively. Reactors were fed once daily, 6 days per week, unless otherwise noted. Influent and digestate total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH, alkalinity, and nitrogen forms were analyzed during the study. Biogas composition (% carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrogen gas (N2)), specific CH4 productivity (mL/g VS-fed), and volatile solids and COD reduction (%) were compared across treatments.

What Have We Learned?

Overall, comparable BMY values were observed across reactors with mean reactor productivity ranging from 275 to 354 mLCH4/g VS-fed. Average BMY for the reactors represented around 61% of typical values of ultimate biomethane potential (BMP) for swine manure reported in the literature, i.e., 450 to 550 mLCH4/gVS. Increasing OLR from 1 to 2 gVS/L-d resulted in a 14% decrease in BMY. The nitrogen treatment effect appears to be minimal and only limited to low OLR treatments. The percentage deviation of biomethane productivity between C and T reactors was less than 1%.

Similar to CH4, concentrations of CO2 were impacted more by OLR than the nitrogen treatment implemented. For low OLR reactors, Average CO2 concentrations in the biogas were for treatment reactors. Increasing the OLR showed an increase in CO2 concentration in the biogas, with control and treatment reactors containing approximately , respectively.

Future Plans

We plan to continue our data analysis to quantify reduction in VS and COD. Similarly, digestate characterization to quantify alkalinity and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) in the feedstock and digestates is ongoing. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be conducted to assess treatment impacts on specific methane yield, VS and COD reduction. Denitrification occurring within reactors was further investigated via GC-TCD headspace analysis. We plan to closely analyze denitrification dynamics to capture the effect of treatment on nitrogen forms and organic matter in the substrates.

Authors

Presenting author

Kristina E. Jones, Graduate student researcher, North Carolina State University

Corresponding author

Mahmoud A. Sharara, PhD, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist, North Carolina State University, Msharar@ncsu.edu

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Pancopia, Inc. as part of a Department of Energy, Small Business Innovation Research program grant (DOE SBIR, Grant No. DE-SC0020833). Authors would like to acknowledge Smithfield Foods for access and support sampling. and undergraduate student researchers: Brian Ngo, Nick Bell, Kiarra Condon, Himanth Mandapati, and Jackson Boney for assistance and support conducting this study.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Co-recovery of phosphorus from manure using acid precursors contained in other wastes.

Purpose

A new approach for recovering nutrients and value-added products from waste is to search for a synergistic effect by combining two or more wastes. This work improved the recovery of phosphorus and proteins/amino acids abundant in swine manure by adding a second waste or product rich in sugars, such as molasses, fruit waste, or lactose waste. The second waste rich in sugars acted as a natural acid generator that replaced purchased acids and lowered the overall recovery cost.

What Did We Do?

A new approach was developed to separate and recover concentrated phosphorus and proteins from animal waste (Vanotti and Szogi, 2019). It was improved by adding a second waste or product containing sugars, such as molasses and fruit waste (Vanotti et al., 2020). They could be used as a natural acid precursor that replaces purchased acids and lowers the overall cost of phosphorus and protein recovery. In this study, the two model wastes were swine manure solids (source of extractable phosphorus and proteins) and peach waste (source of acid precursors).

What Have We Learned?

On a dry-weight basis, the swine manure solids contained high amounts of proteins (15.2%) and phosphorus (2.9%) available for extraction. It was shown that waste peaches, an abundant waste in the Southeastern USA with no cost except transportation, contain about 8% total sugars and can be used as an acid precursor to effectively extract phosphorus and proteins from swine manure (waste peaches were peaches that were too soft, had bad spots, or did otherwise not meet the grade at the Processing Plant for sale as fresh fruit). The waste peaches (Brix 7.7 deg) were added to the manure, and the combo received rapid fermentation (24-h) after adding an inoculum (Vanotti et al., 2020). Adding fruit waste to the manure and rapid fermentation produced abundant natural acids – lactic acid, citric acid, and malic acid – that effectively solubilized the phosphorus in the manure (Fig. 1). Further, the peach fermentation did not adversely affect the protein recovery from the manure. A pH of about five or less is a valuable target to optimize the phosphorus and protein recovery from manure. The target was successfully met using a variety of natural acid precursors (fructose, molasses, peaches, lactose). The phosphorus was precipitated with calcium or magnesium compounds, obtaining concentrated phosphate products with > 90% plant-available phosphorus. The proteins/amino acids in the manure were quantitatively recovered. Other fruits, vegetables, and food waste products also contain significant amounts of sugar, so this is not limited to only wasted peaches. It is contemplated that other sugar-containing agricultural by-products could be used in this process for the same purpose with minor adjustments for amounts depending on the sugar concentration and initial pH of the fruit or vegetable.

Future Plans

Research will be presented showing consistent phosphorus extraction results obtained with swine manure and sugar beet molasses as the acid precursor, and with dairy manure and lactose waste as the acid precursor. USDA-ARS seeks a commercial partner to bring this technology to market. For more information on commercialization, contact: Mrs. Tanaga Boozer, Technology Transfer Coordinator, USDA-ARS, OTT Southeast Area, tanaga.boozer@usda.gov

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Matias Vanotti, USDA-ARS, Matias.vanotti@usda.gov

Additional authors

Vanotti, M.B, Szogi, A.A., and Brigman, P.W. USDA-ARS, Florence, SC

Moral, R. Miguel Hernandez University, Orihuela, Spain

Additional Information

Vanotti, M.B., Szogi, A.A. 2019. Extraction of amino acids and phosphorus from biological materials. US Patent 10,150,711. US Patent & Trademark Office.

Vanotti, M.B., Szogi, A.A., Moral, R. 2020. Extraction of amino acids and phosphorus from biological materials using sugars (acid precursors). US Patent 10,710,937. US Patent & Trademark Office.

Vanotti, M., Szogi, A., Moral, R., & Brigman, W. 2023 (November). Recovery of Value-Added Products from Swine Manure and Waste Peaches. In National Conference on Next-Generation Sustainable Technologies for Small-Scale Producers (NGST 2022) (pp. 38-42). Atlantis Press.

Acknowledgements

This research was part of USDA-ARS National Program 212, ARS Project 6082-12630-001-00D. Support by Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Japan, through ARS Project 58-6082-7-006-F, is also acknowledged. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Enhancing Phosphorus Recovery from Anaerobically Digested Dairy Effluent Using Biochar and FeCl₃ in a Rotary Belt Filter System

Purpose

This work aims to conduct pilot-scale trials using a rotary belt filter (RBF) with biochar to recover nutrients at a dairy anaerobic digestor and produce an upcycled bioproduct for soil amendment (Figure 1). Anaerobically digested (AD) effluents contain large quantities of phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), and organic carbon, while biochar is a reactive material that has potential for use to recover nutrients and prevent nutrient loss. Biochar was used as a strategy to enhance phosphorus (P) recovery by improving total suspended solids (TSS) removal efficiency in the RBF system. This approach was further extended to include iron chloride (FeCl3) as a flocculant, which has potential to efficiently remove suspended solids as well as soluble phosphorus from wastewater.

To optimize P recovery, laboratory-scale experiments were conducted to evaluate biochar and iron chloride dosing rates. These experiments aimed to better understand the system’s performance and provide insights for pilot scale studies. The goal was to develop a lab setup that accurately represents field conditions and to identify cost-effective, practical solutions for large-scale applications.

What Did We Do?

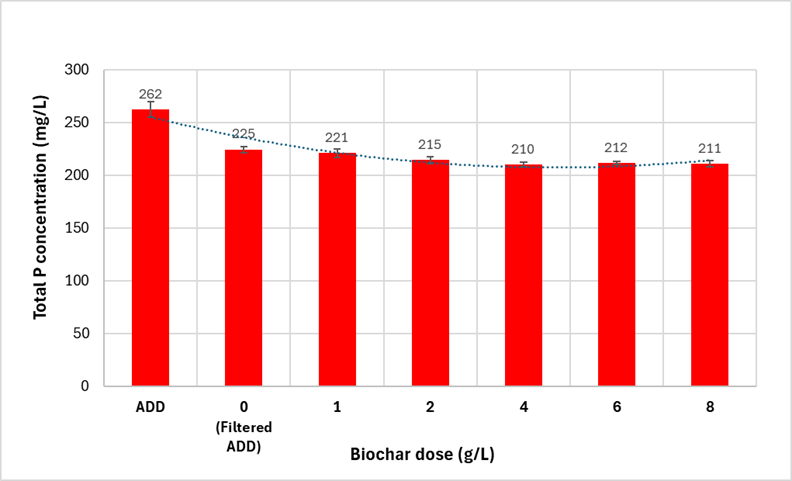

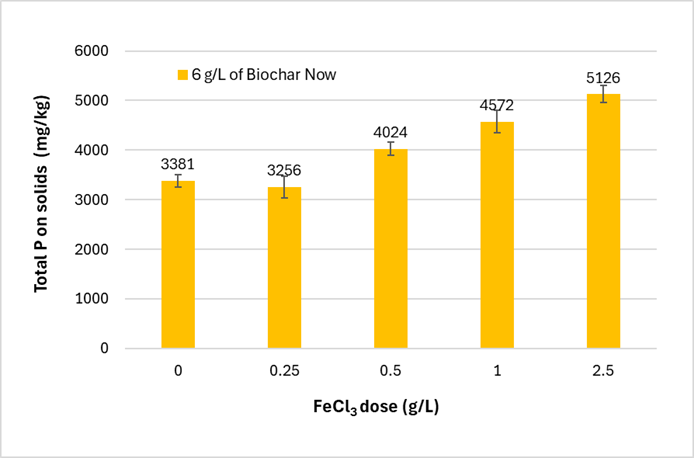

Biochar dosing experiments were conducted using a jar test, in which 30 mL of AD dairy effluent was mixed with biochar (Biochar Now LLC., Loveland, Colorado) for 20 minutes at 200 rpm, with dosing rates of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 g/L. For the iron chloride dosing experiments, 6 g/L of biochar was mixed with the effluent for 20 minutes at 200 rpm, followed by the addition of iron chloride to achieve final concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 g/L. The Fe-biochar mixtures were then stirred for 1 minute at 200 rpm and subsequently for 20 minutes at 40 rpm. After mixing, the samples were vacuum filtered using the same mesh of the rotating belt filter (112 mesh or 149 μm) on a 2” Buchner ceramic funnel. Since sedimentation time introduces variability to the flocculation process, a filtration setup was designed to allow simultaneous filtration of replicates. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

The solids retained on the mesh were collected, air-dried overnight, and digested using a modified dry ash method. Part of the filtrate was used for total suspended solids (TSS) analysis, while another portion was digested following the acid digestion method for sediments, sludges, and soils (EPA 3025B). The digested solid and filtrate samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm PES syringe filter and analyzed for elemental composition using an ICP spectrometer.

What Have We Learned?

The TSS of the AD dairy effluent can vary seasonally. In our experiments, the batch used contained approximately 25,000 mg/L of SS. The filtration system retains up to 15% of the SS when no biochar or Fe are amended to the AD. The addition of 4 to 6 g/L of biochar increased TSS removal by 5%. However, higher biochar doses did not further enhance TSS removal efficiency.

Results indicated that most of the P in the AD dairy effluent is not in the soluble reactive form, which means that P removal in the rotary belt filter should be proportional to the TSS removal. Figure 2 shows the P concentration in the filtered effluent from the biochar dosing experiments, indicating that with biochar additions ranging from 2 to 8 g/L, the P concentration in the filtrate remains similar. Figure 3 shows that the P concentration in the solids decreased as the biochar dose increased. This is because the total mass of solids retained on the filter increased with the addition of biochar. These results showed that biochar has a dilution effect on P concentration because the phosphorus removal capacity of biochar during filtration is limited.

Figure 4 shows the P concentration on solids at different doses of FeCl3 added to 6 g/L of biochar. The results show that higher FeCl3 doses lead to higher P concentrations in the solids. Table 1 shows the relationship between FeCl₃ dosing rates and the estimated volume of iron chloride solution needed in a pilot scale field trial. With 6 g/L of biochar, achieving an increase in P concentration from ~3300 mg/L to 5000 mg/L would require 6 L/m³ of FeCl3 solution. pH adjustments would optimize iron promoted flocculation and significantly reduce the amount of iron dosing required, and thus process costs. However, due to the high buffering capacity of the AD effluent, large amounts of acid would be required, which would offset cost savings from the reduced iron amendment.

| Field scale | |

| FeCl3 dose (g/L) | FeCl3 (L/m3) |

| 0 | 0 |

| 0.1 | 0.24 |

| 0.25 | 0.60 |

| 0.50 | 1.21 |

| 1.00 | 2.41 |

| 2.50 | 6.03 |

Future Plans

The next steps of this research are divided into two main topics. The first focuses on evaluating the effect of organic flocculants, such as chitosan and alginate, on TSS and phosphorus removal from the effluent. This includes analyzing their advantages and disadvantages compared to iron chloride. The second topic explores the oxidation of the effluent with ozone before flocculant addition. This approach aims to determine whether pre-oxidation can reduce the required flocculant dose per mg of TSS removed.

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Mariana C. Santoro, Postdoctoral researcher, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho, marianacoelho@uidaho.edu

Additional authors

Daniel G. Strawn, Professor, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

Martin C. Baker, Research Engineer, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

Alex Crump, Research Scientist, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

Gregory Möller, Professor, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Training Development for On-Farm Anaerobic Digester Operators

Purpose

This presentation documents the development of a new training program to be offered by North Carolina Extension (NC Extension), or other qualified entities, to serve on-farm digester operators in the state. This program was developed in response to increased adoption of on-farm anaerobic digestion (AD) systems in North Carolina, particularly on swine farms. With proliferation of on-farm digesters and the accompanying methane purification and transfer infrastructure, the availability of adequate training and support to ensure their safe and sustainable operation was a growing concern.

In North Carolina, the Water Pollution Control System Operators Certification Commission (WPCSOCC) was established, by NC General Statutes 143B-300 and 143B-301, to oversee training and certification of water pollution control system operators. During their quarterly meetings, the commissioners discussed this need and engaged North Carolina State University (NC State University), the 1860 land-grant institution, to provide expertise and support over development and administration of this training program.

What Did We Do?

The training development proceeded over the following steps:

-

- Need-to-know (NTKs) compilation: A team of five members representing NC Extension (the authors), NC Department of Environmental Quality (NC DEQ), and WPCSOCC met at regular intervals (three meetings in total, each 1.5 to 2 hours) to summarize key learning objectives that need to be met by the training program. External stakeholders representing animal industry, digester installers, and farm inspectors were consulted for input and comment on NTKs list (two one-on-one meetings). The NTKs were grouped by topic and divided into five (5) modules. Once finalized, the NTKs were submitted for approval by WPCSOCC during their regular meetings.

- Training material development: Once the learning objectives were approved, NC Extension team started compiling resources (factsheets, PowerPoint slide decks) from existing NC Extension training materials on the topic, and resources made available by colleagues in peer institutions to prepare training content. Other training content delivered by land-grant and industry associations were consulted during this step. WPCSOCC and NC DEQ representatives also provided some input on content. The developed content was 3-hours in length.

- Test offering: Once training material was developed, a group of 10 county extension agents with livestock training responsibilities were invited for the first offering of the training. They were encouraged to document impressions, comments, and provide feedback. Changes were made to address gaps, adjust pacing, and include more accessible graphics and data.

- Official offering: Two sessions were held in September and October 2024 for the following audiences [1] NC DEQ inspectors and supervisors (28 attendees) in Raleigh, NC, and [2] animal producers/operators who operate AD systems, as well as those considering investing in AD systems in Kenansville, NC (36 attendees).

- Feedback and continued learning: Feedback and questions by attendees were addressed in both sessions. In the second session, a county extension director facilitated compiling questions and shared them with the training leader to address. An open Zoom session was coordinated to bring expertise from regulatory agencies, the swine production sector, and AD technology installers to address these questions collectively. The answers were compiled into a frequently asked questions (FAQs) list that was reviewed by attendees before distribution and publishing on NC Extension portal, NC Swine Newsletter, and relevant trade magazines.

What Have We Learned?

Feedback and interactions with trainees showed growing interest in adopting on-farm anaerobic digesters primarily driven by the monetary value of biomethane sale as a renewable natural gas (RNG). Some cost-share programs further lowered the barrier to entry for many producers. Primary concerns/disincentives include profitability for small and medium size farms, impacts on nutrient management planning, and compliance. The training described above provides an opportunity to engage project developers/installers during the program to provide examples of adoption models without disclosing proprietary information. Clear delineation of responsibilities for the AD system between farm manager, operators, and project team supervision continues to be a priority.

Future Plans

Twice per year offering of the training is planned. Experiential and peer learning through field tours and testimonials by operators of ADs are planned for future offerings. A homepage for AD related content was developed on NC Extension portal including an opportunity to ask questions on the topic. The FAQ list will be continuously updated to answer new and emerging questions.

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Mahmoud Sharara, Associate Professor and Extension Specialist, Biological and Agricultural Engineering Department, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, msharar@ncsu.edu

Additional author

Mark Rice, Extension Specialist (retired), Biological and Agricultural Engineering Department, North Carolina State University, jmrice@ncsu.edu

Additional Information

-

- Portal for Manure Anaerobic Digesters on NC Extension webpage: https://animalwaste.ces.ncsu.edu/digest/

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) answered RE: on-farm ADs: https://animalwaste.ces.ncsu.edu/2024/11/ad_faqs/

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Bob Rubin, WPSOCC board member and retired NCSU faculty, Patrick Biggs (NC DEQ), Jeffrey Talbott (NC DEQ), Christine Lawson (NC DEQ), Gus Simmons (Cavanaugh and Associates) , and Smithfield Foods for feedback, assistance, and insights provided during training development.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Bang for Your Buck: Developing Effective Anaerobic Digestion Policies for Carbon Emission Reduction

Purpose

Anaerobic digesters are an established technology for reducing methane emissions from livestock manure. In recent years, the rapid expansion of renewable natural gas (RNG) projects, driven by economic incentives such as Renewable Identification Number (RIN) credits, Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) credits, and Investment Tax Credits (ITC) from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, has spurred significant growth in RNG production. These incentives, while promoting the adoption of anaerobic digestion, may only sometimes be the most cost-effective way to achieve meaningful carbon reductions within the livestock sector. RNG production, electricity generation via biogas, and flaring biogas all mitigate agricultural greenhouse gas (sometimes referred to as carbon dioxide equivalence or CO2e) emissions from manure. Nonetheless, electric generators are significantly cheaper than the biogas upgrading systems necessary for RNG production, and flares are significantly cheaper than electric generators.

Our analysis compares system costs and emissions reductions, and investigates the societal benefit featured by each system. The only revenue we analyze is RNG sales and electricity sales; we do not incorporate carbon credits into the revenue stream. Flaring biogas, or the process of burning the methane within biogas to produce the lesser potent greenhouse gas, CO2, greatly reduces agricultural CO2e emissions, though this process does not generate usable renewable energy. Electricity generation via biogas is cheaper than RNG production via biogas, but electricity can be sustainably generated with more efficient methods, such as wind turbines and solar panels. RNG is primarily created via anerobic digestion; additionally, RNG is the leading renewable replacement for conventional natural gas, a fossil fuel with increasing use, traveling within 3,000,000 miles of pipelines in the U.S. Nonetheless, RNG remains an expensive and technically complex process, requiring high capital investment and persistent, local, and skilled labor for effective operation.

What Did We Do?

This study compares the economic and carbon reduction potential of various anaerobic digestion biogas uses, including RNG production, electricity generation, and flaring. By evaluating the carbon savings and cost-effectiveness of these options, the study provides policymakers insights on optimizing public funding and incentives for the livestock industry. Furthermore, we provide livestock farmers with a decision support tool that balances the environmental benefits of anaerobic digestion with the most efficient use of financial resources to foster clean and sustainable livestock production system.

What Have We Learned?

Table 1 summarizes dollars per megagram (MG) of CO2e mitigated via RNG production, electricity production via biogas, and flaring biogas for both covered manure storages and constructed anaerobic digesters. Five scenarios were compared for farms featuring dairy cows, swine with lagoon manure storages, and swine with deep pit manure storages to analyze the carbon credit value (units of dollars per MG of CO2e mitigated) necessary to financially break even on the project. Flaring biogas featured the lowest necessary break-even carbon credit for dairy, swine farms with lagoon manure storage, and swine farms with deep pit manure storages. If a farmer wants to generate power, then generating electricity requires a lesser carbon credit value per MG CO2e mitigated compared to RNG generation. If a farmer wants to generate power via RNG, and carbon credits exist in units of dollars per energy, then a dairy farmer would be more profitable with a digester, whereas a swine farmer would be more profitable with a covered manure storage.

If a governing body is interested in maximizing its livestock manure CO2e reduction given a set amount of tax dollars, then the governing body may be most interested in incentivizing flaring systems. If a governing body is interested in both power generation via livestock manure and CO2e reduction, then the governing body may be most interested in incentivizing electricity generation. Nonetheless, renewable electricity can be generated more efficiently by a variety of methods, whereas RNG is the most prominent fossil natural gas replacement and primarily created via anaerobic digestion. Furthermore, as the electric grid “greens”, or as the CO2e emissions associated with grid electricity decrease, RNG generation will provide an overall greater percent CO2e reduction.

Deep pit swine farms generating electricity or RNG demonstrated CO2e reduction that was greater than 100%. Deep pit swine farms have less emissions than lagoon swine farms. By converting a deep pit swine farm to an outdoor covered manure storage or digester system, methane production increases, though that methane is now used for renewable energy generation, thereby offsetting fossil energy generation.

| Head | Dairy: 2,000 | Swine – Lagoon: 14,000 | Swine – Deep Pit: 14,000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CO2e (MG/yr) | 10,654 | 10,179 | 3,980 | ||

| Covered Storage | Flaring | CO2e Mitigated (MG/yr) | 8,786 | 8,786 | 3,424 |

| % CO2e Reduction | 82% | 86% | 86% | ||

| $/yr Profit (10-year life) | ($84,137) | ($108,151) | ($342,975) | ||

| Break-Even ($/MG CO2e Mitigated) Carbon Credit | $10 | $12 | $100 | ||

| Covered Storage | Electricity | CO2e Mitigated (MG/yr) | 9,734 | 9,735 | 4,373 |

| % CO2e Reduction | 91% | 96% | 110% | ||

| $/yr Profit (10-year life) | ($178,978) | ($202,992) | ($437,816) | ||

| Break-Even ($/MG CO2e Mitigated) Carbon Credit | $18 | $21 | $100 | ||

| Break-Even ($/kWh) Carbon Credit | $0.08 | $0.09 | $0.20 | ||

| Covered Storage | RNG | CO2e Mitigated (MG/yr) | 9,913 | 9,914 | 4,552 |

| % CO2e Reduction | 93% | 97% | 114% | ||

| $/yr Profit (10-year life) | ($780,801) | ($795,726) | ($1,030,551) | ||

| Break-Even ($/MG CO2e Mitigated) Carbon Credit | $79 | $80 | $226 | ||

| Break-Even ($/MMBTU) Carbon Credit | $46 | $47 | $61 | ||

| Digester | Electricity | CO2e Mitigated (MG/yr) | 10,042 | 9,826 | 4,464 |

| % CO2e Reduction | 94% | 97% | 112% | ||

| $/yr Profit (10-year life) | ($557,022) | ($519,566) | ($754,390) | ||

| Break-Even ($/MG CO2e Mitigated) Carbon Credit | $55 | $53 | $169 | ||

| Break-Even ($/kWh) Carbon Credit | $0.14 | $0.19 | $0.27 | ||

| Digester | RNG | CO2e Mitigated (MG/yr) | 10,169 | 9,904 | 4,542 |

| % CO2e Reduction | 95% | 97% | 114% | ||

| $/yr Profit (10-year life) | ($1,207,287) | ($1,056,809) | ($1,291,633) | ||

| Break-Even ($/MG CO2e Mitigated) Carbon Credit | $119 | $107 | $284 | ||

| Break-Even ($/MMBTU) Carbon Credit | $39 | $50 | $62 |

Future Plans

The project life of biogas upgrading equipment, pipeline interconnects, electric generators, and flares are not always the same. We intend to further investigate the project lives of different equipment to calculate more accurate annualized costs and payback periods. Furthermore, we will analyze how the economies of scale compare between biogas upgrading equipment, electric generators, and flares by evaluating costs of equipment necessary for various farm sizes. Lastly, we would like to further define and quantify the overall societal impact created by RNG production, electricity production via biogas, and flaring biogas.

Authors

Presenting author

Luke Soko, Graduate Student, Iowa State University

Corresponding author

Dan Andersen, Associate Professor, Iowa State University, dsa@iastate.edu

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Using an interactive map exercise to help producers better manage their manure

Purpose

Time and time again, experience has taught us that many people learn by doing, not just from listening to presentations. The Nebraska Animal Manure Management Team has worked hard over the last six years to develop and expand what is now referred to as the Interactive Nutrient Management Decision-Making Exercise. This workshop will serve as a train-the-trainer event where attendees will:

-

- Discover how the exercise began and what it has grown to include

- Get familiar with the pieces and parts by helping set up the activity

- Experience a couple of the activities as participants

- Hear from others that have adapted the exercise and their experiences

- Brainstorm how the exercise can be used elsewhere or for other concepts

What Did We Do?

The Interactive Nutrient Management Decision-Making Exercise (mapping exercise) was developed by the Animal Manure Management Team at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and University of Minnesota to engage participants during Manure Application Trainings. In Nebraska, these trainings previously relied heavily on PowerPoint and recorded presentations, but with many people being hands-on learners, an interactive exercise was proposed. In 2020, the original 6 activities were used for the afternoon portion, and it has since grown to the exercise it is today that is incorporated throughout the whole-day training.

It has been used not only for livestock producers but also crop producers. Parts of it have been modified to fit into workshops at conferences and, most recently, high school classrooms. Current expansion topics include spray drift to avoid sensitive areas and nitrogen management from all sources.

What Have We Learned?

Because many livestock producers in Nebraska are required to attend Land Application Training events every five years to maintain their Livestock Waste Control Facility permit, the winter 2024-2025 programming season for the Nebraska manure team offered an opportunity to ask participants how their operations have changed since the first time they had seen the Interactive Nutrient Management Decision-Making Exercise (in 2020). The team asked 3 questions specific to the exercise and changes on their operations and found the following results.

In general, participants are considering the topics taught during training more now than they were five years ago. The figure below indicates that 48% consider weather forecasts to decrease odor risk more or much more than they did prior to experiencing the Interactive Nutrient Management Decision-Making Exercise. Forty eight percent and 59% consider water quality and soil health impacts from manure more than five years ago, subsequently. While many participants already factored in transportation cost compared to nutrient value captured for a field, 59% reported that they consider it more or much more than they did, and 55% reported that they now considered the value of manure nutrients based on a field’s soil test more or much more.

We also asked participants to share with us how useful they felt the changes and expanded activities of the Interactive Nutrient Management Decision-Making Exercise were. All participants felt that the changes and expansion were useful with 52% indicating that they were very or extremely useful.

We also asked, “How do you expect your experience with the newer activities of the interactive nutrient management decision-making exercise will change your operation in the future?” and, among others, we received the following responses:

-

- “[we will] take more consideration to neighbors near application”

- “[we will make] better $ management decision[s] on manure application site[s]”

- “[the activity] makes us want to plan out better to get better results”

Future Plans

With so much success using this teaching tool, we would like to expand it to teach topics other than nutrient management. The Soil Health Nexus, a soil health workgroup in the north central region of the US, is in the process of developing an adaptation of this tool that will teach participants about the impacts of certain practices on soil health. Currently, progress has been made on activities focusing on tillage and the use of cover crops. Other planned activities include a focus on crop rotation and the use of the Soil Health Matrix, a tool developed by the Soil Health Nexus.

The Nebraska Animal Manure Management team, as part of a different grant, also has plans to create some activities focused on integrating livestock into cropping systems.

We also support using the base model of this exercise and adapting it for other practices and audiences outside of Nebraska.

Authors

Presenting & Corresponding author

Leslie Johnson, Animal Manure Management Extension Educator, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, leslie.johnson@unl.edu

Additional author

Amy Millmier Schmidt, Professor and Livestock Bioenvironmental Engineering Specialist, University of Nebraska-Lincoln;

Additional Information

Downloadable Curriculum: https://lpelc.org/interactive-nutrient-management-decision-making-exercise-curricula/

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all other contributors to the curriculum in the past including:

-

- Larry Howard, Rick Koelsch, Agnes Kurtzhals, Aaron Nygren, Agustin Olivio, Amber Patterson, Katie Pekarek, Amy Schmidt, Mike Sindelar, and Todd Whitney (University of Nebraska, Lincoln)

- Daryl Andersen, Tyler Benal, Will Brueggemann, Russ Oakland, and Bret Schomer (Lower Platte North NRD)

- Blythe McAfee and Tiffany O’Neill (Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy)

- Andy Scholting (Nutrient Advisors)

- Marie Krausnick, Dan Leininger (Upper Big Blue NRD)

- Chryseis Modderman (University of Minnesota)

- Nutrient Advisors

- Settje Agri Services Eng.

- Ward Laboratories Inc.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.