Purpose

This work aims to conduct pilot-scale trials using a rotary belt filter (RBF) with biochar to recover nutrients at a dairy anaerobic digestor and produce an upcycled bioproduct for soil amendment (Figure 1). Anaerobically digested (AD) effluents contain large quantities of phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), and organic carbon, while biochar is a reactive material that has potential for use to recover nutrients and prevent nutrient loss. Biochar was used as a strategy to enhance phosphorus (P) recovery by improving total suspended solids (TSS) removal efficiency in the RBF system. This approach was further extended to include iron chloride (FeCl3) as a flocculant, which has potential to efficiently remove suspended solids as well as soluble phosphorus from wastewater.

To optimize P recovery, laboratory-scale experiments were conducted to evaluate biochar and iron chloride dosing rates. These experiments aimed to better understand the system’s performance and provide insights for pilot scale studies. The goal was to develop a lab setup that accurately represents field conditions and to identify cost-effective, practical solutions for large-scale applications.

What Did We Do?

Biochar dosing experiments were conducted using a jar test, in which 30 mL of AD dairy effluent was mixed with biochar (Biochar Now LLC., Loveland, Colorado) for 20 minutes at 200 rpm, with dosing rates of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 g/L. For the iron chloride dosing experiments, 6 g/L of biochar was mixed with the effluent for 20 minutes at 200 rpm, followed by the addition of iron chloride to achieve final concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 g/L. The Fe-biochar mixtures were then stirred for 1 minute at 200 rpm and subsequently for 20 minutes at 40 rpm. After mixing, the samples were vacuum filtered using the same mesh of the rotating belt filter (112 mesh or 149 μm) on a 2” Buchner ceramic funnel. Since sedimentation time introduces variability to the flocculation process, a filtration setup was designed to allow simultaneous filtration of replicates. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

The solids retained on the mesh were collected, air-dried overnight, and digested using a modified dry ash method. Part of the filtrate was used for total suspended solids (TSS) analysis, while another portion was digested following the acid digestion method for sediments, sludges, and soils (EPA 3025B). The digested solid and filtrate samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm PES syringe filter and analyzed for elemental composition using an ICP spectrometer.

What Have We Learned?

The TSS of the AD dairy effluent can vary seasonally. In our experiments, the batch used contained approximately 25,000 mg/L of SS. The filtration system retains up to 15% of the SS when no biochar or Fe are amended to the AD. The addition of 4 to 6 g/L of biochar increased TSS removal by 5%. However, higher biochar doses did not further enhance TSS removal efficiency.

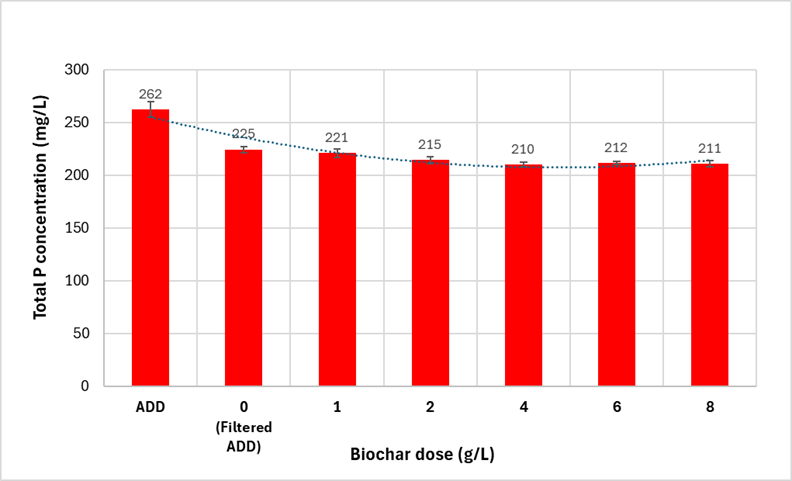

Results indicated that most of the P in the AD dairy effluent is not in the soluble reactive form, which means that P removal in the rotary belt filter should be proportional to the TSS removal. Figure 2 shows the P concentration in the filtered effluent from the biochar dosing experiments, indicating that with biochar additions ranging from 2 to 8 g/L, the P concentration in the filtrate remains similar. Figure 3 shows that the P concentration in the solids decreased as the biochar dose increased. This is because the total mass of solids retained on the filter increased with the addition of biochar. These results showed that biochar has a dilution effect on P concentration because the phosphorus removal capacity of biochar during filtration is limited.

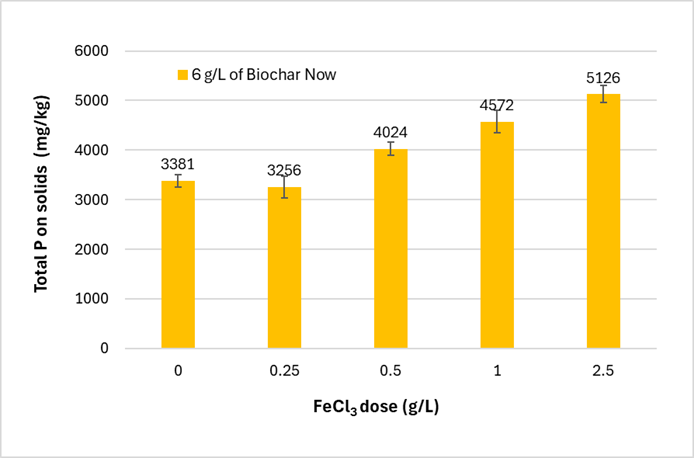

Figure 4 shows the P concentration on solids at different doses of FeCl3 added to 6 g/L of biochar. The results show that higher FeCl3 doses lead to higher P concentrations in the solids. Table 1 shows the relationship between FeCl₃ dosing rates and the estimated volume of iron chloride solution needed in a pilot scale field trial. With 6 g/L of biochar, achieving an increase in P concentration from ~3300 mg/L to 5000 mg/L would require 6 L/m³ of FeCl3 solution. pH adjustments would optimize iron promoted flocculation and significantly reduce the amount of iron dosing required, and thus process costs. However, due to the high buffering capacity of the AD effluent, large amounts of acid would be required, which would offset cost savings from the reduced iron amendment.

| Field scale | |

| FeCl3 dose (g/L) | FeCl3 (L/m3) |

| 0 | 0 |

| 0.1 | 0.24 |

| 0.25 | 0.60 |

| 0.50 | 1.21 |

| 1.00 | 2.41 |

| 2.50 | 6.03 |

Future Plans

The next steps of this research are divided into two main topics. The first focuses on evaluating the effect of organic flocculants, such as chitosan and alginate, on TSS and phosphorus removal from the effluent. This includes analyzing their advantages and disadvantages compared to iron chloride. The second topic explores the oxidation of the effluent with ozone before flocculant addition. This approach aims to determine whether pre-oxidation can reduce the required flocculant dose per mg of TSS removed.

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Mariana C. Santoro, Postdoctoral researcher, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho, marianacoelho@uidaho.edu

Additional authors

Daniel G. Strawn, Professor, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

Martin C. Baker, Research Engineer, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

Alex Crump, Research Scientist, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

Gregory Möller, Professor, Department of Soil and Water Systems, University of Idaho

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

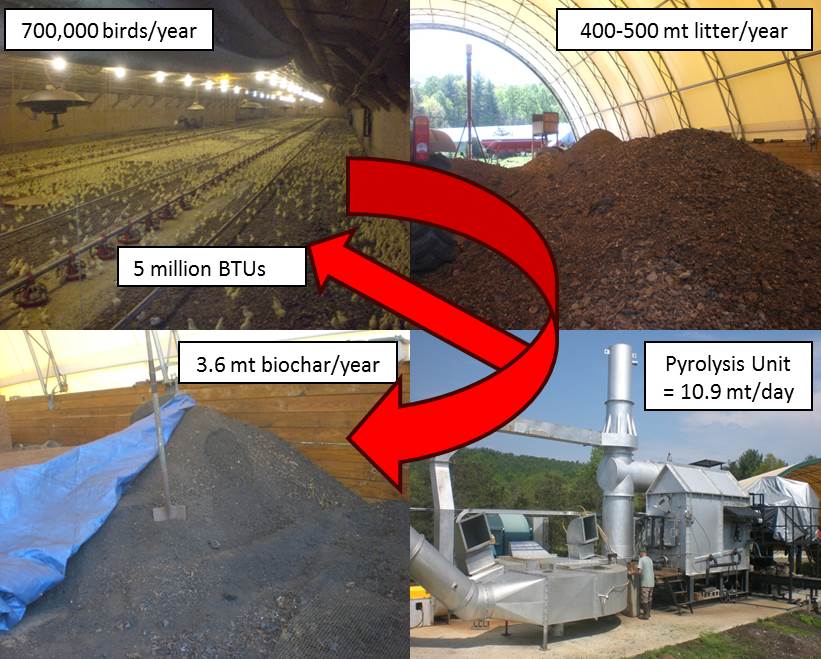

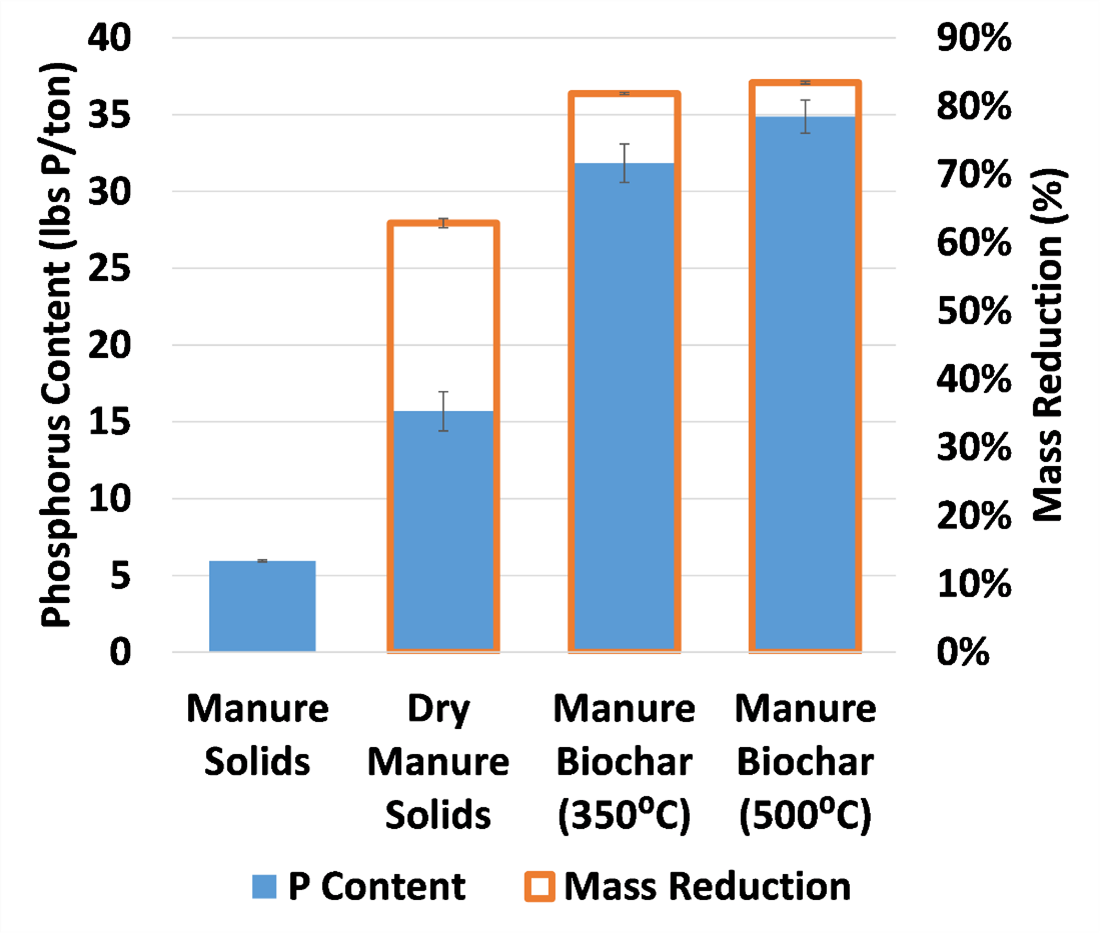

volumes are significantly reduced. With the nutrients being concentrated, they are more easily handled and can be transported from areas of high nutrient loads to regions of low nutrient loads at a lower cost. This practice can also help to reduce the on-farm energy costs by providing supplemental energy and/or heat. Additional benefits include pathogen destruction and odor reduction. This presentation will provide an overview of several Conservation Innovation Grants (CIG) and other manure thermo-chemical conversion projects that are being demonstrated and/or in commercial operation. Information will cover nutrient fate, emission studies, by-product applications along with some of the positives and negatives related to thermo-chemical conversion systems.

volumes are significantly reduced. With the nutrients being concentrated, they are more easily handled and can be transported from areas of high nutrient loads to regions of low nutrient loads at a lower cost. This practice can also help to reduce the on-farm energy costs by providing supplemental energy and/or heat. Additional benefits include pathogen destruction and odor reduction. This presentation will provide an overview of several Conservation Innovation Grants (CIG) and other manure thermo-chemical conversion projects that are being demonstrated and/or in commercial operation. Information will cover nutrient fate, emission studies, by-product applications along with some of the positives and negatives related to thermo-chemical conversion systems. What did we do?

What did we do?  What have we learned?

What have we learned?  Author

Author