Purpose

Poultry production is the number one agricultural enterprise in value of production for South Carolina with approximately 280,000,000 birds in inventory. Poultry litter as a by-product of poultry production is a low-cost fertilizer that can provide nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and micronutrients for forage systems. Poultry litter can improve soil fertility and health by adding organic matter and enhancing water infiltration and soil fertility over time on more than 300,000 acres of forages in South Carolina.

Yet, despite purported benefits to the pasture system and use as a fertilizer to improve forage, questions remain for livestock producers looking to apply poultry litter to their pastures. There is a lack of information about the availability, cost, and quality of litter. With the increase in interest in poultry litter applications as a climate-smart agricultural practice or to participate in conservation programs, this work is expected to assist regional producers in understanding poultry litter attributes and inform purchasing decisions.

What Did We Do?

Using a dataset of 68 producers utilizing poultry litter and the corresponding transactions, we characterize the availability and market for poultry litter in South Carolina. Data on transactions, including prices paid, delivery date, application rate, and county-level location of litter, forms the basis for analysis. Also, we use sample analysis results to compare nutrient price with commercial fertilizer nutrient values.

What Have We Learned?

Of the 68 producers reporting data, 45 reported detailed price, location and application information. An exploration of prices paid per ton of litter across the state suggests differences based on location (Table 1). Based on the results of a t-test, higher prices are observed for the mid-state compared to the upstate (statistically significant at 6% level for two tail t-test). Differences in prices observed by season appear but are not statistically significantly different based on ANOVA tests.

| Midstate (n=20) | Upstate (n=25) | Average | |

| Fall | 25.55 | 22.32 | 23.30 |

| Spring | 32.13 | 22.55 | 28.02 |

| Summer | 22.31 | — | 22.31 |

| Winter | — | 19.33 | 19.33 |

| Average | 27.37 | 22.02 | 24.40 |

Other findings from the data could be helpful to design outreach and assist producers looking to purchase litter for their operation. Some other interesting information includes the type of litter: broiler, layer, turkey, and other sources. Also, of the producers in the sample, 19 were unable to find litter with the majority of producers located in the Upstate area (74%).

Next, for the approximately 40 samples that included nutrient analysis, a summary of mean and standard deviation of pounds per ton of ammonium N, organic N, P205 and K20 are given in Table 2. From prices reported by each producer, the cost per pound of nutrient is also calculated. From here, average fertilizer and nutrient prices were gathered for South Carolina and displayed in Table 3. Similar costs can be seen when comparing the average cost per pound for each nutrient (Table 2) to the average price per pound for commercial fertilizers (Table 3). For example, the average cost of a pound of ammonium N from the poultry litter sources was $2.46/lb and $2.45/lb from commercial sources.

| Nutrients | ||||

| Ammonium N (lbs./ton) | Organic N (lbs./ton) | P205 (lbs./ton) | K20 (lbs./ton) | |

| n | 41 | 40 | 42 | 42 |

| mean | 10.04 | 50.21 | 47.15 | 51.65 |

| std dev | 3.93 | 15.09 | 20.41 | 21.04 |

| $/# | $2.46 | $0.49 | $0.52 | $0.48 |

| South Carolina Average Fertilizer Prices FY2024 | ||||

| DAP (18%-46%-0%) | Urea (46%) | 10-10-10 | Potash (60%) | |

| Mean | $881.00 | $504.45 | $489.00 | $482.45 |

| Std. Dev. | $8.02 | $13.30 | $5.72 | $13.05 |

| N ($/#) | $2.45 | $0.55 | $2.45 | $0.00 |

| P ($/#) | $0.96 | $0.00 | $2.45 | $0.00 |

| K ($/#) | $0.00 | $0.00 | $2.45 | $0.40 |

Source: South Carolina Crop Production Report (Monthly), Livestock, Poultry, and Grain Market News, USDA Agricultural Marketing Service.

Future Plans

Findings and data from this analysis will first be prepared for outreach and dissemination efforts to producers across the state. Information will also be summarized for current enrollees in the grant program. Finally, given that this data was collected as part of a five-year study, data will be collected in subsequent years. Ultimately, a hedonic analysis of poultry litter attributes to help understand differences in price as a result of nutrient attributes, storage conditions, type, and trucking could inform producer sourcing of litter and prices paid.

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Nathan B. Smith, Extension Economist, Clemson University, nathan5@clemson.edu

Additional authors

Anastasia W. Thayer, Assistant Professor, Clemson University; Matthew Fischer, Extension Associate, Clemson University; Maggie Miller, Extension Associate, Clemson University.

Additional Information

https://www.climatesmartsc.org/

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement number NR2338750004G049.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

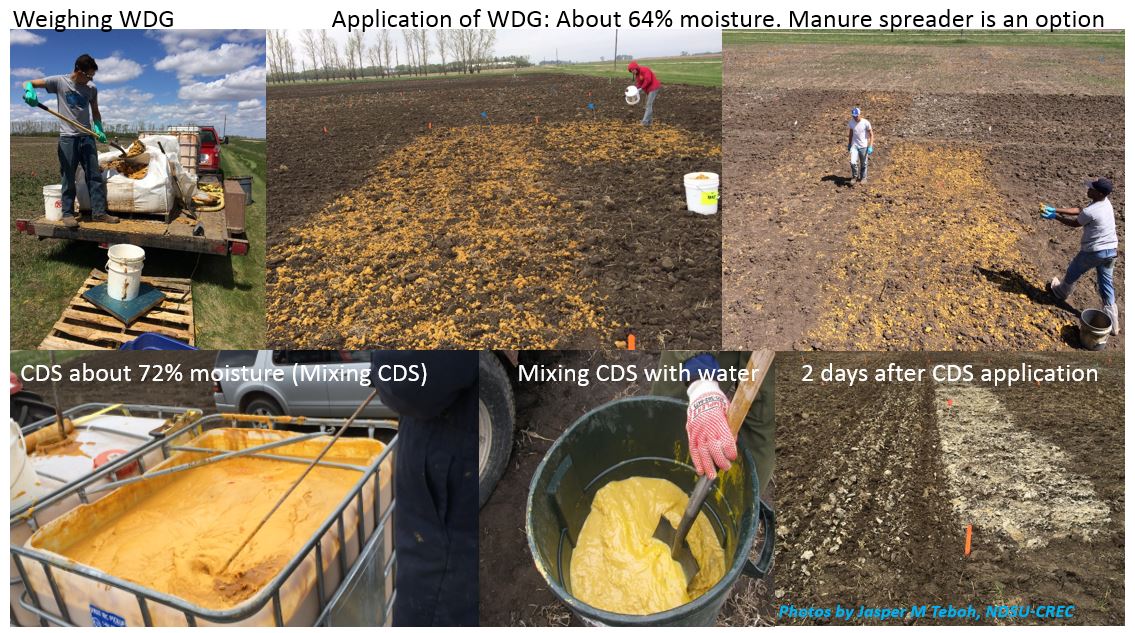

A patented treatment process, called “Quick Wash”, was developed for extraction and recovery of phosphorus from animal manure solids, but research has shown that the approach is equally effective with municipal biosolids. In the Quick Wash process, phosphorus is selectively extracted from pig manure solids by using mineral or organic acid solutions. Following, phosphorus is recovered by addition of liquid lime and an organic poly-electrolyte to the liquid extract to form a calcium-containing P precipitate. The quick wash process generates two products: 1) manure solids low in phosphorus; and 2) recovered phosphorus material.

A patented treatment process, called “Quick Wash”, was developed for extraction and recovery of phosphorus from animal manure solids, but research has shown that the approach is equally effective with municipal biosolids. In the Quick Wash process, phosphorus is selectively extracted from pig manure solids by using mineral or organic acid solutions. Following, phosphorus is recovered by addition of liquid lime and an organic poly-electrolyte to the liquid extract to form a calcium-containing P precipitate. The quick wash process generates two products: 1) manure solids low in phosphorus; and 2) recovered phosphorus material.