Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

There is a worldwide concern in controlling the anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. GHGs pertinent to this paper, include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) and are measured in CO2 equivalents (CO2 eq.). On a 100-year basis, CH4 is 34 times as potent as CO2, while N2O is 298 times as potent as CO2 (IPCC, 2013); CO2 eq. is referred to as the global warming potential (GWP) of these gases. The carbon from feed used on a dairy farm originally comes from CO2 recently removed from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and so has a neutral impact on climate change. However, carbon that is converted to CH4 and N2O is a significant concern since their GWPs are much higher. Dairy farms create GHG emissions when they use fossil fuel-based sources to provide energy for the farm, when importing fertilizer to grow crops and to harvest milk. However, emissions from the animals in the form of enteric CH4 and GHGs from manure management ! are much more significant due to the GWP. While every farm is different, estimates from Thoma et al. (2012) show that of the 34.9 Tg of CO2 eq. in the US dairy supply chain, 19% comes from feed production and 53% comes from milk production. Of the milk production, CO2 eq., 49% is from enteric emissions while 44% is from manure management, predominately from CH4 emissions from manure storages.

New York State, the third largest dairy state in the nation (NASS, 2015), has established ambitious overall renewable energy goals including incorporating 50% renewable energy in the electricity used in the State by 2030 (Energy to Lead, 2015) and reducing GHG emissions 40% by 2040 based on 1990 year baseline values (Executive Order, 2009). The New York State Public Service Commission (PSC) is charged with the responsibility of developing a system that encourages utilities to help meet these goals. This includes reforming the energy vision, a new clean energy standard that is being developed to value electric products from distributed energy sources that includes an economic value for the environmental attributes (E).

An attempt at quantifying the environmental benefits of AD (E) might be expressed as follows:

Etotal=∑▒〖Eghg+Eair quality+Ewater quality+Esoil quality+E…〗

As the State’s renewable energy goals are realized, there needs to be a way for the process to include special provisions for those renewable energy sources that have extra societal benefits, including economic and environmental, and that support the rural character of upstate NY. The dairy industry is New York’s leading agricultural sector, accounting for more than one-half of the state’s total agricultural receipts. The increased milk supply has been very important in helping to meet the tremendous growth in the production of yogurt in NYS. However, the margin between the cost of producing milk and the price received for milk sales, is shrinking. Investing in farm facilities like ADSs will need to be analyzed carefully to ensure a return on investment that merits their implementation. An economic value for the environmental attributes of electricity produced from an ADS would aid in the analysis, showing a more positive overall benefit.

Dairy farms are also under increasing pressure to improve conditions environmentally. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) proposed revisions for the CAFO state permit, regulating the water quality impact of farms with more than 300 cows, will require manure storages to be built to limit spreading on at-risk fields during the winter and early spring seasons. These are farm sizes where manure-based ADSs have been built in the past and where many more could be implemented, given a reasonable rate of return. Manure storages are an important best management practice (BMP) to reduce the potential for water pollution by allowing farms to avoid manure spreading during inappropriate times. Unfortunately, if the manure system does not have a way to capture the GHGs produced, they are released into the atmosphere. Manure-based ADSs installed on farms would be a win-win-win to capture and reduce GHGs and to produce renewable energy from the captured! CH4, fur thermore helping to meet the NYS renewable energy and GHG reduction goals. ADSs installed on farms would stimulate the rural economy and also provide the farm and rural community with all the additional benefits contained in Appendix A.

This paper presents an analysis of the GHG reduction potential for a NYS dairy manure management system that includes AD, post-digestion solid-liquid separation (SLS) and long-term manure storage of SLS liquid effluent. This system is representative of almost all of the 27 ADSs currently operating on-farm in NYS today.

METHODS

The mass of GHG emission reductions (i.e., the mass of carbon dioxide equivalents [MT CO2 eq.]) associated with AD (in this analysis, AD followed by SLS with liquid effluent stored long-term) located in New York State (NYS), was quantified and is discussed in this paper. The following protocols were used: IPCC (2006), AgSTAR (2011), and EPA (Federal Register, 2009) combined with reasonable input values that are representative of a farm’s baseline condition (long-term manure storage with no pre-treatment by ADS). The reductions quantified include: 1) the replacement of fossil fuel-based electrical energy by using AD produced biogas to operate an on-site engine-generator set, and 2) GHG emissions from CAFO required (for water quality purposes) long-term manure storages. The difference between the baseline condition and the conditions post-implementation of an ADS yields the farm’s net GHG emission associated with manure storage. To quantify the economic value! of the G HG emission reductions, the EPA social cost of carbon (SC-CO2) was used (EPA, 2016).

What did we do? *

PROCEDURE

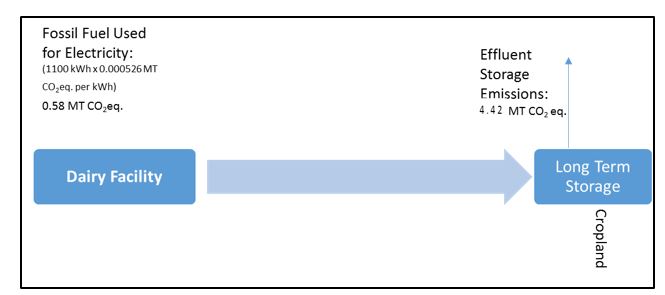

The baseline condition is represented in Figure 1. Typical liquid/slurry long-term manure storages have manure that consists of urine plus feces, solid bedding and milking center washwater, added continuously as is produced on the farm. A natural crust may form as lighter organic material floats to the surface. The storages are constructed as a designed earthen storage with 2:1 side slopes or fabricated from concrete or steel. The fabricated structures have straight sides so less surface area is exposed. A few storages have a SLS prior to storage, while very few have a manure storage cover. Without a cover, they are exposed to rainfall from both annual precipitation and from extreme storms. To determine the baseline condition, storage with no SLS and with a natural crust was considered.

Figure 1. Baseline Emissions from Dairy Farm with No Renewable Energy System (Per cow per year)

Establish Long-Term Manure Storage Baseline Emissions

Part I – Estimating typical CH4 emissions from a long-term manure storage

An independent panel of experts agreed (USDA, 2014) that GHG emission reductions are best estimated using the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) Tier 2 method. For long-term manure storages, the daily methane emissions can be calculated by using Equation 1.

Equation 1. ECH4 = VS x Bo x 0.67 x (MCF/100)

where:

ECH4 = Mass of CH4 emissions (kg CH4/cow-day)

VS = Mass of volatile solids in manure going to storage (kg/cow-day)

Bo = Maximum volume of CH4 producing capacity for manure (m3 CH4/kg VS)

= 0.24 m3 CH4/kg VS (for dairy cow manure)

0.67 = Conversion factor for m3 CH4 to kg CH4

MCF = CH4 conversion factor for the manure management system

Yearly CH4 emissions (kg CH4/cow-yr.) can be estimated by summing the daily emissions (or multiplying an average representative daily emission by 365 days). The MCF is largely dependent on the temperature and the type of manure management system. The MCF will change throughout the year as the manure storage temperature changes. Using a summer ambient temperature representative of Upstate New York, of 18°C (64°F) and a winter ambient temperature of < 10°C (< 50°F), a farm can limit the amount stored and the time in storage during the warmer months to reduce the average yearly MCF. Different manure systems also have a different MCF based on the oxygen levels, interception of CH4 gases, and moisture content.

The two variables that can be controlled by the farm management are the VS loading per cow and the methane conversion factor (MCF). The VS loading rate can be reduced by any pre-manure storage treatment process that reduces the storage organic loading rate; fine tuning the diet to reduce VS in the manure and SLS are examples of two methods used to control the VS.

Typically in NYS, manure is stored both in the summer and winter in a liquid/slurry system with no natural crust. Using average typical winter and summer manure storage temperatures, average MCF values can be used in Equation 1 to estimate average methane emissions for these 6-month storage periods. The MCF values are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Typical Long-Term Manure Storage Methane Conversion Factors for Storage Periods in NYS1

| Storage Period |

Winter |

Summer |

| Average Manure Storage Temperature (°C) |

<10 |

18 |

| MCF |

17 |

35 |

1These numbers are based on liquid/slurry storage without a natural crust cover. (Source: IPCC, 2006)

Using these MCF values shown in Table 1 and a per-cow VS excretion rate of 7.7 kg/cow-day (representative of high producing NY dairy cows – ASABE, 2006), manure storages could be estimated to produce 38 kg CH4/cow (for the winter storage period) and 79 kg CH4/cow (for the summer storage period) or an average of 4 metric tons (MT) of CO2 eq. per cow per year since 1 kg of CH4 = 34 kg CO2 eq.

Part II – Estimating typical N2O emissions from a long-term manure storage

There could be N2O emissions from a raw manure storage facility. The CO2 equivalent from N2O emissions can be estimated by using Equation 2.

Equation 2. CO2eq = 298 CO2/N2O GWP x EF3 x N x44 N2O/28 N2O-N

where:

CO2eq = Equivalent global warming potential expressed as carbon dioxide

298 CO2/N2O = GWP factor for N2O

EF3 = Emission Factor for N2O-N emissions from manure management

N = Mass of N excreted per cow per day = 0.45 kg/cow-day (ASAE, 2005)

Using an EF3 value of 0.005 (USEPA, 2009) for long-term storage of slurry manure with a crust and multiplying it by 0.45 kg of N/cow-day and by 365 days per year yields an additional 0.38 MT of CO2 eq. per cow per year from N2O emissions from a long-term manure storage facility.

Summary of long-term storage GHG emissions

Combining both the CO2 eq. per cow per year from CH4 emissions and the CO2 eq. per cow per year from N2O emissions from a manure storage facility provides a baseline emission of 4.38 MT of CO2 eq. per cow per year from the manure storage systems that the NYS CAFO permit requires. These emissions can be mitigated by implementing a renewable energy system including an ADS with SLS of the digestate before storage.

Establish GHG Emissions and Emission Reductions for an ADS

If a manure-based ADS was installed on a farm, it could reduce the GHG emissions from manure management as well as replace fossil fuel use or energy for both the farm and other users. By capturing the CH4 produced, and combusting it for energy or simply flaring the excess, CH4 releases are converted back to the neutral CO2 originally consumed by the animals in the form of feed products. The ADS could help to meet NYS renewable energy and GHG reduction goals, however, farms with an ADS would need to manage the system to minimize leaks. With no incentives to control leaks, the CH4 produced potentially could add to overall farm GHG emissions.

Part I – Estimating typical CH4 emissions and emission reductions

There are a number of factors that need to be taken into consideration when estimating the GHG reductions that an ADS will provide. Leaks in the ADS can be very detrimental as more methane is produced in an ADS than is emitted naturally from a manure storage facility in the baseline condition. In addition, there are uncombusted CH4 losses from flares and even some from the engine as well. Although every farm system is different, typical values can be determined from the literature, on-farm measurements, and experience.

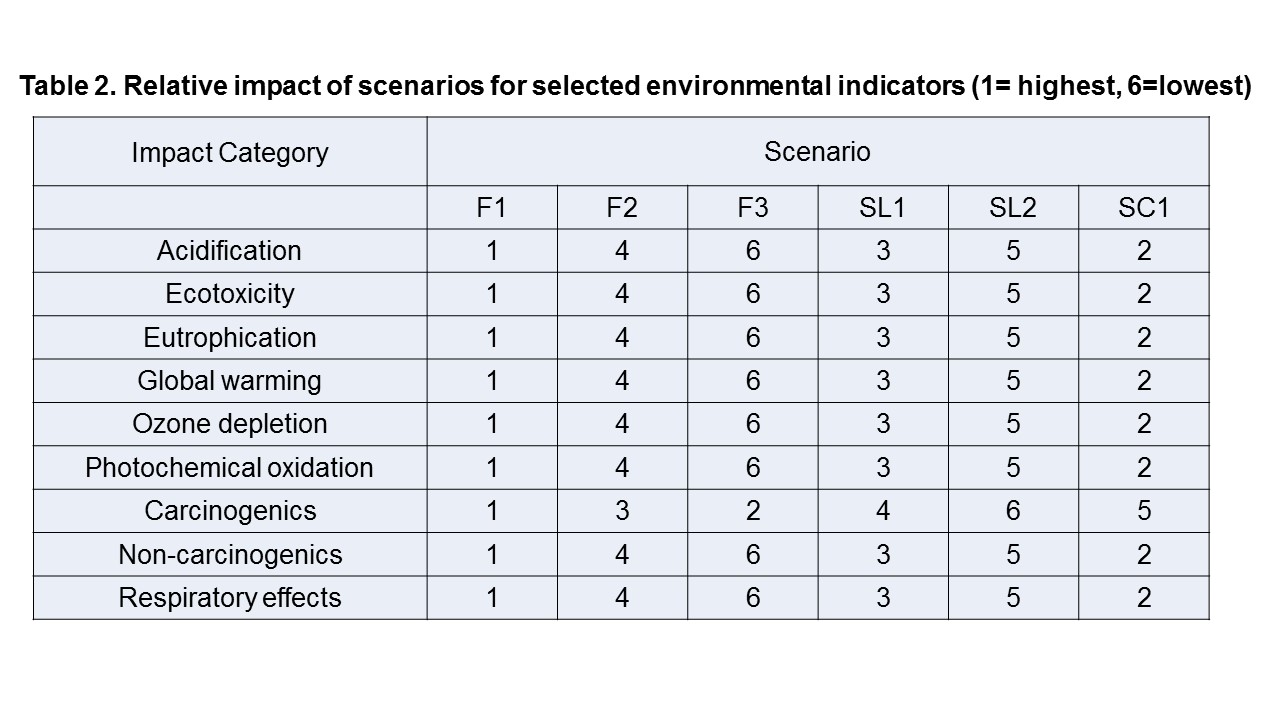

ADSs designed and built to supply only the quantity of electricity consumed on-farm and to reduce odors may not be as effective as systems designed specifically to reduce GHG emissions. The conservative values in Table 2 could be used to describe these types of systems. ADSs built specifically to reduce GHG emissions in addition to maximizing the renewable energy produced would achieve significantly better GHG reductions. The optimum numbers are achievable, while the obtainable values are based on ADSs that consider GHG emissions and are built to optimize CH4 production.

Table 2. ADS variables that can be controlled by the system equipment, operation, and management

|

Conservative |

Optimum |

Obtainable |

Reference |

|

| Leaks from system (% CH4) |

10 |

0 |

1 |

AgSTAR (2011) and on-farm |

| Flare Efficiency (%) |

90 |

99 |

95 |

AgSTAR (2011) and on-farm |

| Engine capacity factor (decimal) |

0.85 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

On-farm measurements |

| Engine efficiency (%) |

38 |

42 |

38 |

On-farm measurements |

| ADS Parasitic load

(kWh/cow-yr) |

0.30 |

0.07 |

0.18 |

On-farm measurements |

| Biodegradability post-digestion (%) |

70 |

50 |

60 |

On-farm measurements |

| VS left after SLS (%) |

60 |

20 |

50 |

On-farm measurements |

The additional societal benefit of this technology can be calculated using EPA’s SC-CO2 of $47.82 as the 2017-2019 average SC CO2 value per metric ton of C02 eq. (at a 3% discount rate) for the methane and nitrous oxide emissions (EPA, 2016).

Part II – Estimating typical N2O emissions and emission reductions for an ADS

An EF3 value of 0 (IPCC, 2006) for an uncovered liquid manure storage describes the typical emission factor from an ADS with SLS since post-digestion there would be no free oxygen, and after solids removal, there would not be a crust forming.

The resulting calculations from the conservative, optimum and obtainable ADS values are shown in Table 3. The fossil fuels avoided are based on the kilo-Watt hours (kWh) produced minus the parasitic load. The uncombusted CH4 from the engine is based on a rich burn engine. The CO2 equivalents from the system leaks and the digestate storage are the major emissions in the conservative scenario, the uncombusted emissions from the flare and the digestate storage are minor emissions from the optimum scenario, while storage contributes the most to the continuing emissions from the obtainable scenario.

Table 3. GHG Emissions from electric production converted with a $47.82 SC-CO2 into a value of E for conservative, optimum and obtainable ADS with solid separation of the digestate before storage.

| Units | Conservative | Optimum | Obtainable | ||

|

MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

0.70 |

1.16 |

0.99 |

|

| Engine uncommuted CH4 | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

2.5 x 10-3 |

3.2 x 10-3 |

3.1 x 10-3 |

|

| Flare uncommuted CH4 | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

0.19 |

0.00 |

0.03 |

|

| System Leaks CH4 | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

1.41 |

0.00 |

0.14 |

|

| Storage emissions CH4 | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

2.98 |

0.50 |

1.9 |

|

| ƩCO2eq emitted – FF avoided | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

3.81 |

0.65 |

1.06 |

|

| Baseline | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

4.38 |

4.38 |

4.38 |

|

| Reduction in CO2eq | MT CO2 eq/cow-yr |

0.57 |

5.03 |

3.32 |

|

| SC-CO2 Benefit | $/cow-yr |

$27 |

$240 |

$149 |

|

| Gross Electricity produced | kWh/cow-yr |

1,590 |

2,229 |

1,955 |

|

| Value of E | $/kWh |

0.017 |

0.11 |

0.081 |

Summary of long-term storage GHG emissions

The obtainable value of E $0.081/kWh, for an ADS with SLS of the digestate could be used to better determine the value of renewable energy in meeting NYS’s goals of reducing GHG emissions, increasing renewable energy, and supporting the dairy industry and the upstate NY economy.

More specific values for each individual ADS could be determined as a more granulated value (i.e., a value based on a more detailed/thorough analysis) through the implementation of NYS’s renewable energy vision. By using a value of E that reflects the actual environmental benefit of an ADS, this would incentivize dairy farms with an ADS to improve their CH4 production to produce more electrical energy. This would also increase the interest of more dairy farms in controlling GHG emissions and producing renewable energy by investing in ADS on their farms.

What have we learned?

ADSs can be used to reduce the manure management generated GHG emissions from dairy farms. With careful management, 3.32 MT of CO2 eq. per cow-year can be credited to the ADS. Using EPA’s SC-CO2 average price during 2017-2019 of $47.82, this could amount to a GHG benefit of over $140/cow-year. At this time, the benefit to society is unrewarded and high costs for ADSs both to construct and to operate, discourage farms from installing them. Working towards New York State’s renewable energy goals, as well as the reduction in GHG emission goals by compensating farms for the societal value of $0.081 per kWh of electricity produced from a well-run ADS would better incentivize farms to both install and operate ADSs to the advantage of the State.

Future Plans

DISCUSSION

ADSs can provide additional GHG reductions by utilizing organic wastes that currently go to landfills or aerobic waste treatment facilities. Some landfills may be able to capture a portion of the CH4 that the organic waste produces as renewable energy, but typically the leaks from a landfill gas recovery system are greater than those of farm-based ADS. NYS has some interest in diverting organic waste from landfills to reduce: the fill rate, the potential GHG emissions, and O&M costs in landfills. The value of the diverted organic waste can be best recovered by society if the energy is recovered through manure-based AD since the nutrients would also be recovered by mixing the food waste with manure, digesting it and recycling the nutrients in the effluent to the land for growing crops.

Nutrients to grow crops that are currently utilized in the form of commercial fertilizer, could be offset by the nutrients contained in a post-digested liquid, which would also reduce the energy and accompanying fossil fuel emissions now emitted when manufacturing commercial nutrients.

Aerobic treatment of organic wastes requires additional energy that adds to the fossil fuel-based carbon dioxide emissions and typically does not recover nutrients. While anaerobic digestion creates renewable energy and preserves nutrients.

Typical ADSs produce a large portion of energy from CH4 as waste heat from the engine(s). Operating a Combined Heat and Power (CHP) system in conjunction with an enterprise that would utilize the heat produced, would enable the system to harvest even more renewable energy.

ADSs could improve GHG mitigation efforts if the effluent storage was covered and if the gas collected was included in the biogas utilization system, eliminating any emissions from the effluent storage while producing even more renewable energy.

Farm Disadvantages

Managing a complex and expensive ADS requires dedication and a sophisticated management effort that clearly competes for time with other tasks on the farm. There is the potential to emit excess CH4 if: 1) leaks are not properly controlled, 2) the engine generator, boiler and/or flare are not efficient or 3) if the effluent storage continues to produce uncontained CH4. These can all be compounded if off-site organics are imported to the farm. The existing NYS net metering program makes the current price paid for exported electricity, very low. This reduces the motivation to produce and capture the maximum amount of CH4 from the ADS.

Planning and installing an on-farm ADS takes time to consider the benefits and costs so that a business decision can be reached. Capital costs of ADSs vary, but can range from $4,000 to $5,500 per kW of generation capacity. Operating costs have been estimated at $0.02 to $0.03 per kWh. Much of the capital investment is considered lost capital by lenders. The existing manure management system should be examined to determine any disadvantages from extra solids, contaminants, or dilution. If the successful operation of the ADS depends on tipping fees from imported organics, the reliability and quality of these sources needs to be determined. If electricity is to be sold, the utility should be consulted to determine how/if the distribution lines to the farm can handle what is expected to be generated.

Corresponding author, title, and affiliation

Peter Wright, Agricultural Engineer, Cornell University

Corresponding author email

Other authors

Curt Gooch, Dairy Environmental Systems and Sustainability Engineer, Cornell University

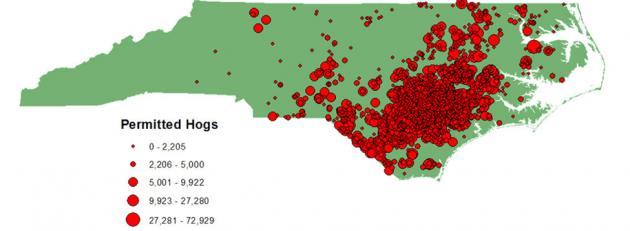

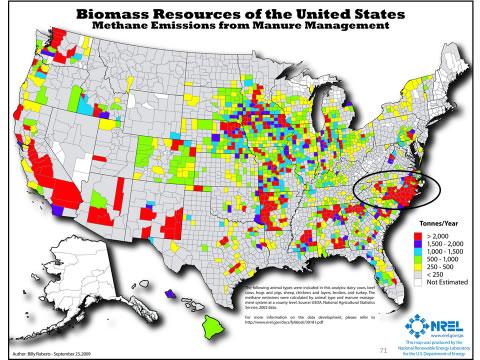

forward-thinking farmers have learned that their waste is valuable for supplying renewable energy, it has been unfortunately difficult for an individual farmer to implement and manage advanced value recovery systems primarily due to costs of scale. Rather, it seems, success may be easier achieved through the aggregation of these products from several farms and through the collaborative efforts of project developers, product offtakers, and policy. A shining example of such aggregation and collaboration can be observed from the Optima-KV swine waste to pipeline renewable gas project, located in eastern North Carolina in an area of dense swine farm population.

forward-thinking farmers have learned that their waste is valuable for supplying renewable energy, it has been unfortunately difficult for an individual farmer to implement and manage advanced value recovery systems primarily due to costs of scale. Rather, it seems, success may be easier achieved through the aggregation of these products from several farms and through the collaborative efforts of project developers, product offtakers, and policy. A shining example of such aggregation and collaboration can be observed from the Optima-KV swine waste to pipeline renewable gas project, located in eastern North Carolina in an area of dense swine farm population. required, which presented challenges of negotiating multiple utility connections and agreements. This learning curve was steepened as, at the time of the inception of Optima KV, the state of North Carolina lacked formal pipeline injection standards, so the final required quality and manner of gas upgrading was established through the development of the project.

required, which presented challenges of negotiating multiple utility connections and agreements. This learning curve was steepened as, at the time of the inception of Optima KV, the state of North Carolina lacked formal pipeline injection standards, so the final required quality and manner of gas upgrading was established through the development of the project.