Due to a technical glitch, the beginning of the recorded presentation was not recorded. Please accept our apologies.

Purpose

As the adoption of dairy manure storage systems has increased as a best management practice for protecting water quality, the anaerobic conditions in these systems has inadvertently led to an increase in emission of the greenhouse gas methane. Current inventory and modeled estimates of this potent greenhouse gas are based on limited datasets, and there is a need for methodologies to better quantify these emissions so that the impacts of storage conditions, manure treatments and seasonality can be better assessed, mitigation strategies can be implemented, and greenhouse gas reduction estimates can be correctly accounted for.

What Did We Do?

We are developing a ground-based, mobile measurement approach where manure storage systems are circled with a backpack methane gas analyzer and measurements are integrated with on-site wind measurements to calculate emission flux rates. Twelve commercial dairy farm manure storage systems, representing a range of herd sizes and pre-storage manure treatments are collaborating on the research. Once per month, each manure storage structure at each site is circled 10 consecutive times with a methane gas analyzer. A drone equipped with a separate methane analyzer is also used to verify ground-based measurements amidst the methane plumes. Divergence (Gauss’s) theorem is then applied to concentration measurements and anemometer wind data to estimate the net rate of methane flux. These observed methane emission fluxes are compared to International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) modeled emissions as well as state inventories.

We are developing a ground-based, mobile measurement approach where manure storage systems are circled with a backpack methane gas analyzer and measurements are integrated with on-site wind measurements to calculate emission flux rates. Twelve commercial dairy farm manure storage systems, representing a range of herd sizes and pre-storage manure treatments are collaborating on the research. Once per month, each manure storage structure at each site is circled 10 consecutive times with a methane gas analyzer. A drone equipped with a separate methane analyzer is also used to verify ground-based measurements amidst the methane plumes. Divergence (Gauss’s) theorem is then applied to concentration measurements and anemometer wind data to estimate the net rate of methane flux. These observed methane emission fluxes are compared to International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) modeled emissions as well as state inventories.

What Have We Learned?

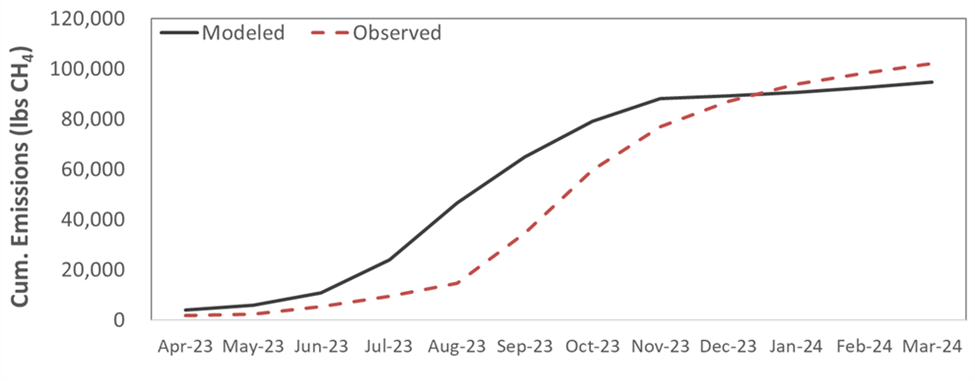

We find that this methodology provides a reliable, cost-effective way to estimate methane emissions from manure storages. Observed emissions track modeled emissions with similar magnitudes, though models may be overestimating emissions during the growing season and underestimating during the winter months in this region (Figure 1). While emissions patterns are generally similar for each of the farm sites, with some farms and some individual monthly observational estimates there can be substantial deviation from predicted emission rates.

We find that this methodology provides a reliable, cost-effective way to estimate methane emissions from manure storages. Observed emissions track modeled emissions with similar magnitudes, though models may be overestimating emissions during the growing season and underestimating during the winter months in this region (Figure 1). While emissions patterns are generally similar for each of the farm sites, with some farms and some individual monthly observational estimates there can be substantial deviation from predicted emission rates.

- Figure 1. Modeled and measured cumulative methane emissions from a dairy manure storage system over a 12-month period.

Future Plans

Evaluation of 2024 field data is ongoing, and we will continue to measure methane around storages with ground-based and drone measurements into the summer of 2025. We will explore plume dynamics and the effects of pre-storage treatments on measured methane emission flux. For select sites, measurements will be expanded to include continuous, open-path laser absorption spectroscopy to verify this novel measurement approach, footprint emissions, and explore the implications of pre-storage manure treatments.

Evaluation of 2024 field data is ongoing, and we will continue to measure methane around storages with ground-based and drone measurements into the summer of 2025. We will explore plume dynamics and the effects of pre-storage treatments on measured methane emission flux. For select sites, measurements will be expanded to include continuous, open-path laser absorption spectroscopy to verify this novel measurement approach, footprint emissions, and explore the implications of pre-storage manure treatments.

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Jason P. Oliver, Dairy Environmental Systems Engineer, Cornell University | PRO-DAIRY, jpo53@cornell.edu

Additional authors

Lauren Ray, Agricultural Sustainability and Energy Engineer, Cornell University | PRO-DAIRY

Eric Leibensperger, Associate Professor, Physics and Astronomy, Ithaca College

Additional Information

https://leibensperger.github.io/

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets. Agreement # CM04068CO

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7–11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

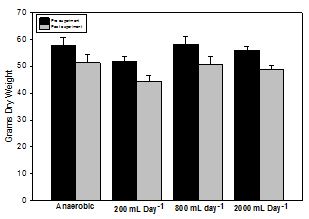

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.