Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

Why aerate biogas digesters?

Most agricultural waste is largely composed of polymers such as lignin and complex carbohydrates that are slowly or nearly completely non-degradable in anaerobic environments. An example of such a waste is chicken litter in which wood chips, rice hulls, straw and sawdust are commonly employed bedding materials. This makes chicken litter a poor candidate for anaerobic digestion because of inherently poor digestibility and, as a consequence, low gas production rates.

Previous studies, however, have shown that the addition of small amounts of air to anaerobic digestates can improve degradation rates and gas production. These studies were largely performed at laboratory-scale with no provision to keep the added air within the anaerobic sludge.

What Did We Do?

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.

Seven dried and weighed tulip poplar disks were added to each tank at the beginning of the experiment. At the end of the experiment, the disks were cleaned and dried for three days at 105 0C before re-weighing. Dissolved and headspace gases were measured on a gas chromatograph equipped with FID, ECD, and TCD detectors. Water quality was measured by standard APHA methods.

What Have We Learned?

Adding 800 mL of air daily increased biogas production by an average of 73.4% compared to strictly anaerobic digestate. While adding 200 mL of air daily slightly increased gas production, adding 2 L per day decreased gas production by 16.7%.

Aerating the sludge improved chemical oxygen demand (COD) with the greatest benefit occurring at 2,000 mL added air per day. As noted, however, this decreased gas production in the control indicating toxicity to the anaerobic sludge.

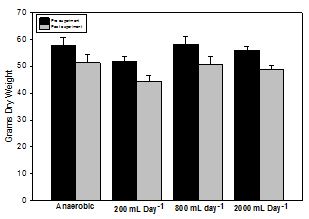

The experiment was stopped after 148 days. When the tanks were opened, there was widespread fungal growth both on the surface of the digestate and the wood disks in the aerated tanks [left], whereas non-aerated tanks showed little evidence of fungal growth [right]. While wood disks subjected to all treatments lost significant mass (t-test, α=0.05), disks in the anaerobic tank lost the least amount of weight on average (6.3 g) while all other treatments lost over 7 g weight on average.

Future Plans

Research on other feedstocks and aeration regimes are being conducted as are 16s and 18s community analyses.

Corresponding author (name, title, affiliation)

John Loughrin, Research Chemist, Food Animal Environmental Research Systems, USDA-ARS, 2413 Nashville Rd. B5, Bowling Green, KY 42104

Corresponding author email address

Other Authors

Karamat Sistani, Supervisory Soil Scientist, Food Animal Environmental Research Systems. Nanh Lovanh, Environmental Engineer, Food Animal Environmental Research Systems.

Additional Information

https://www.ars.usda.gov/midwest-area/bowling-green-ky/food-animal-envir…

Acknowledgements

We thank Stacy Antle and Mike Bryant (FAESRU) and Zachary Berry (WKU Dept. of Chemistry) for technical assistance.