Air quality in and around barns can negatively impact animal and worker welfare. This webinar will discuss ways to overcome these challenges. This presentation originally broadcast on April 21, 2023. Continue reading “Improving Air Quality In and Around Livestock Facilities”

Conservation Planning for Air Quality and Atmospheric Change (Getting Producers to Care about Air)

Purpose

The United States Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS) works in a voluntary and collaborative manner with agricultural producers to solve natural resource issues on private lands. One of the key steps in formulating a solution to those natural resource issues is a conservation planning process that identifies the issues, highlights one or more conservation practice standards that can be used to address those issues, and allows the agricultural producer to select those conservation practices that make sense for their operation. In this conservation planning process, USDA-NRCS looks at natural resource issues related to soil, water, air, plants, animals, and energy (SWAPA+E). This presentation focuses on the resource concerns related to the air resource.

What Did We Do

In order to facilitate the conservation planning process for the air resource, USDA-NRCS has focused on five main issues: emissions of particulate matter (PM) and PM precursors, emissions of ozone precursors, emissions of airborne reactive nitrogen, emissions of greenhouse gases, and objectionable odors. Each of these resource concerns are further subdivided into resource concern components that are mainly associated with different types of sources or activities found on agricultural operations. By focusing on those agricultural sources and activities that have the largest impact on each of these air quality and atmospheric change resource concerns, USDA-NRCS has developed a set of planning criteria for determining when a resource concern exists. We have also identified those conservation practice standards that can be used to address each of the resource concern components.

What Have We Learned

Our focus on the agricultural sources and activities that have the largest impact on air quality has helped to evolve the conservation planning process by adding resource concern components that are targeted and simplified. This approach has led to a clearer definition of when a resource concern is identified, as well as how to address it. For example, the particulate-matter focused resource concern has been divided into the following resource concern components: diesel engines, non-diesel engine combustion equipment, open burning, pesticide drift, nitrogen fertilizer, dust from field operations, dust from unpaved roads, windblown dust, and confined animal activities. Each of these types of sources can produce particles directly or gases that contribute to fine particle formation. In order to know whether a farm has a particulate matter resource concern, a conservation planner would need to determine whether one or more of these sources is causing an issue. Once the source(s) of the particulate matter issue is identified, a site-specific application of conservation practices can be used to resolve the resource concern.

We expect that increased clarity in the conservation planning process will lead to a greater understanding of the air quality and atmospheric change resource concerns and how agricultural producers can reduce air emissions and impacts. Simple and clear direction should eventually lead to greater acceptance of addressing air quality and atmospheric change resource concerns.

Future Plans

USDA-NRCS will continue to refine our approach to addressing air quality and atmospheric change resource concerns. As we gain a greater scientific understanding of the processes by which air emissions are generated and air pollutants are transported from agricultural operations, we can better target our efforts to address these emissions and their resultant impacts. Internally, we will be working throughout our agency to identify those areas where we can collaboratively work with agricultural producers to improve air quality.

Authors

Greg Zwicke, Air Quality Engineer, USDA-NRCS National Air Quality and Atmospheric Change Team

greg.zwicke@usda.gov

Additional Authors

Allison Costa, Air Quality Engineer, USDA-NRCS National Air Quality and Atmospheric Change Team

Additional Information

General information about the USDA-NRCS can be found at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov. An overview of the conservation planning process is available at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/programs/technical/cta/?cid=nrcseprd1690815.

The USDA-NRCS website for air quality and atmospheric change is https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national/air/.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2022. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Oregon, OH. April 18-22, 2022. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Gaseous Emissions from In-house Broiler Litter

Purpose

Broiler litter is a valuable fertilizer but can also be a source of odorous and GHG emissions during production, storage, and land application. Impacts of these emissions are felt by local communities, posing respiratory health impacts and decreased quality of life, as well as increased deposition into soil and water systems. This study seeks to quantify the magnitude of emissions associated with in-house broiler litter and estimate variability across farms. Finally, the study evaluates litter parameters, such as litter age and chemical composition, for gas emission predictors.

What Did We Do?

A set of five active broiler houses in North Carolina were sampled to measure gaseous emissions (NH3, H2S, CH4, N2O, CO2, and VOCs) using headspace flux measurement gas samples. Headspace gas concentrations were measured at 1 hour and 3 hours after incubation at 30°C using a photoacoustic analyzer (Innova 1412) for NH3, CH4, N2O, and CO2 and Jerome 631-X was used to measure H2S, concentration. The headspace was also sampled to quantify VOCs associated with odorous emissions. After incubation, water extraction was used to quantify less volatile organic species that are associated with odorous emissions in the litter. Experimental setup is described in Figure 1. Statistical software, JMP, was utilized for analysis of litter composition on NH3, H2S, CH4, N2O, CO2, and VOC gaseous emissions.

What Have We Learned?

H2S emissions were very low (< 0.01 ppm) and did not produce statistically significant observations. There was a wide range of emissions from the litter samples for different gases as shown in Figure 2: 146-555 ppm NH3, 1.5-22 ppm N2O, 4,077-50,835 ppm CO2, and 9.1-43.3 ppm CH4. The differences between farms accounted for 86%, 81%, 76%, and 84% of the variability in NH3, N2O, CO2, CH4 observations, respectively. This could be attributed to differences in integrator and management strategies. Moisture content and age of the litter were the primary contributing factors to increased gaseous emissions from all samples. More specifically, NH3 was largely impacted by pH (p < 0.01), while N2O, CO2, and CH4 were largely impacted by C:N (p < 0.01). Quantitative VOC analysis was difficult due to the number of gases detected by the GC-MS (20+), however the most common species present in the litter samples were a variety of volatile fatty acids, alcohols, phenol, as well as a few amines, ketols, and terpenes.

Future Plans

These results will serve as baseline emission readings for odor and emission control strategies. We are currently developing Miscanthus-derived biochar as a poultry litter amendment for emission mitigation in poultry houses. This dataset will inform our decision making to help target gaseous species of top concern in NC broiler litter by methods of physical and chemical biochar modification.

Authors

Presenting author

Carly Graves, Graduate Research Assistant, North Carolina State University

Corresponding author

Dr. Mahmoud Sharara, Assistant Professor & Waste Management Extension Specialist, North Carolina State University

Corresponding author email address

msharar@ncsu.edu

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project is through Bioenergy Research Initiative (BRI)- NC Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCDA&CS): Miscanthus Biochar Potential as A Poultry Litter Amendment

Evaluation of current products for use in deep pit swine manure storage structures for mitigation of odors and reduction of NH3, H2S, and VOC emissions from stored swine manure

The main purpose of this research project is an evaluation of the current products available in the open marketplace for using in deep pit swine manure structure as to their effectiveness in mitigation of odors and reduction of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), ammonia (NH3), 11 odorous volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and greenhouse gas (CO2, methane and nitrous oxide) emissions from stored swine manure. At the end of each trial, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia concentrations are measured during and immediately after the manure agitation process to simulate pump-out conditions. In addition, pit manure additives are tested for their impact on manure properties including solids content and microbial community.

What Did We Do?

We are using 15 reactors simulating swine manure storage (Figure 1) filled with fresh swine manure (outsourced from 3 different farms) to test simultaneously four manure additive products using manufacturer recommended dose for each product. Each product is tested in 3 identical dosages and storage conditions. The testing period starts on Day 0 (application of product following the recommended dosage by manufacturer) with weekly additions of manure from the same type of farm. The headspace ventilation of manure storage is identical and controlled to match pit manure storage conditions. Gas and odor samples from manure headspace are collected weekly. Hydrogen sulfide and ammonia concentrations are measured in real time with portable meters (both are calibrated with high precision standard gases). Headspace samples for greenhouse gases are collected with a syringe and vials, and analyzed with a gas chromatograph calibrated for CO2, methane and nitrous oxide. Volatile organic compounds are collected with solid-phase microextraction probes and analyzed with a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Atmospheric Environment 150 (2017) 313-321). Odor samples are collected in 10 L Tedlar bags and analyzed using the olfactometer with triangular forced-choice method (Chemosphere, 221 (2019) 787-783). To agitate the manure for pump-out simulation, top and bottom ‘Manure Sampling Ports’ (Figure 1) are connected to a liquid pump and cycling for 5 min. Manure samples are collected at the start and end of the trial and are analyzed for nitrogen content and bacterial populations.

The effectiveness of the product efficacy to mitigate emissions is estimated by comparing gas and odor emissions from the treated and untreated manure (control). The mixed linear model is used to analyze the data for statistical significance.

What we have learned?

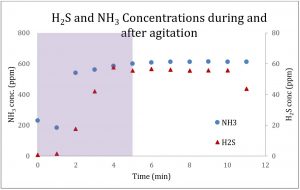

U.S. pork industry will have science-based, objectively tested information on odor and gas mitigation products. The industry does not need to waste precious resources on products with unproven or questionable performance record. This work addresses the question of odor emissions holistically by focusing on what changes that are occurring over time in the odor/odorants being emitted and how does the tested additive alter manure properties including the microbial community. Additionally, we tested the hydrogen sulfide and ammonia emissions during the agitation process simulating pump-out conditions. For both gases, the emissions increased significantly as shown in Figure 2. The Midwest is an ideal location for swine production facilities as the large expanse of crop production requires large fertilizer inputs, which allows manure to be valued as a fertilizer and recycled and used to support crop production.

Future Plans

We develop and test sustainable technologies for mitigation of odor and gaseous emissions from livestock operations. This involves lab-, pilot-, and farm-scale testing. We are pursuing advanced oxidation (UV light, ozone, plant-based peroxidase) and biochar-based technologies.

Authors

Baitong Chen, M.S. student, Iowa State University

Jacek A. Koziel*, Prof., Iowa State University (koziel@iastate.edu)

Daniel S. Andersen, Assoc. Prof., Iowa State University

David B. Parker, Ph.D., P.E., USDA-ARS-Bushland

Additional Information

- Heber et al., Laboratory Testing of Commercial Manure Additives for Swine Odor Control. 2001.

- Lemay, S., Stinson, R., Chenard, L., and Barber, M. Comparative Effectiveness of Five Manure Pit Additives. Prairie Swine Centre and the University of Saskatchewan.

- 2017 update – Air Quality Laboratory & Olfactometry Laboratory Equipment – Koziel’s Lab. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.29681.99688.

- Maurer, D., J.A. Koziel. 2019. On-farm pilot-scale testing of black ultraviolet light and photocatalytic coating for mitigation of odor, odorous VOCs, and greenhouse gases. Chemosphere, 221, 778-784; doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.086.

- Maurer, D.L, A. Bragdon, B. Short, H.K. Ahn, J.A. Koziel. 2018. Improving environmental odor measurements: comparison of lab-based standard method and portable odour measurement technology. Archives of Environmental Protection, 44(2), 100-107. doi: 10.24425/119699.

- Maurer, D., J.A. Koziel, K. Bruning, D.B. Parker. 2017. Farm-scale testing of soybean peroxidase and calcium peroxide for surficial swine manure treatment and mitigation of odorous VOCs, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide emissions. Atmospheric Environment, 166, 467-478. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.07.048.

- Maurer, D., J.A. Koziel, J.D. Harmon, S.J. Hoff, A.M. Rieck-Hinz, D.S Andersen. 2016. Summary of performance data for technologies to control gaseous, odor, and particulate emissions from livestock operations: Air Management Practices Assessment Tool (AMPAT). Data in Brief, 7, 1413-1429. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.03.070.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to (1) National Pork Board and Indiana Pork for funding this project (NBP-17-158), (2) cooperating farms for donating swine manure and (3) manufacturers for providing products for testing. We are also thankful to coworkers in Dr. Koziel’s Olfactometry Laboratory and Air Quality Laboratory, especially Dr. Chumki Banik, Hantian Ma, Zhanibek Meiirkhanuly, Lizbeth Plaza-Torres, Jisoo Wi, Myeongseong Lee, Lance Bormann, and Prof. Andrzej Bialowiec.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2019. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Minneapolis, MN. April 22-26, 2019. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

On-Farm Evaluation of Wood bark-Based Biofilters in Terms of Mitigation of Odor, Ammonia, and Hydrogen Sulfide

Purpose

Mitigating odor and gas emissions is a big challenge facing concentrated animal feeding operations. Biofiltrtion has been recognized as one of the most promising technologies for reducing odor and gas emissions from animal facilities. However, the rate of on-farm biofilter adoption continues to be low. The purpose of this research was to demonstrate, evaluate, and encourage the widespread adoption of biofilters for mitigating odor and gas emissions.

What did we do?

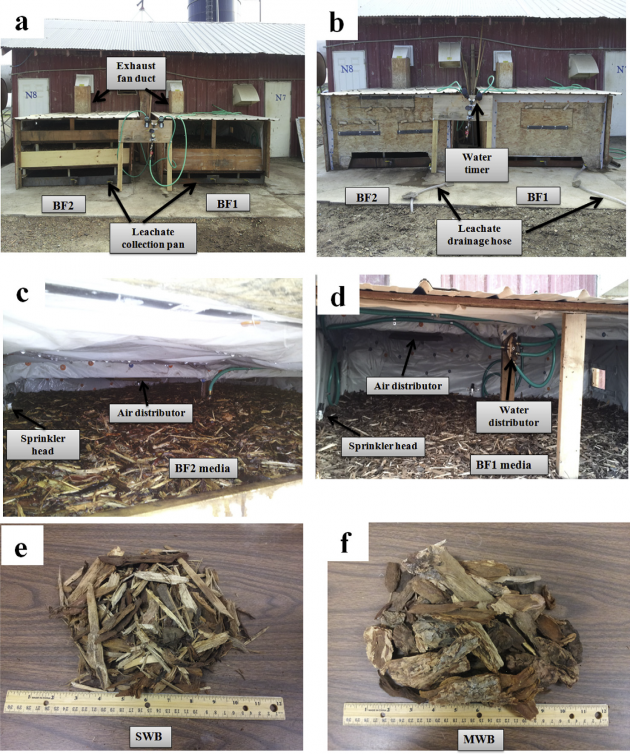

Two vertical down-flow biofilters were constructed on a commercial swine nursery farm. Both biofilter media were shredded wood bark and medium wood bark (1:2 on a volume basis). These biofilters were evaluated under real farm conditions in terms of mitigation of odor and gas emissions. Odor samples were collected using 10 L Tedlar bags and evaluated using a dynamic forced-choice olfactometer. Ammonia and hydrogen sulfide concentrations were monitored on-site by detection tubes. Pressure drop through the biofilter media was also measured on-site using an air velocity meter. A biofilter field day was held on the swine farm to demonstrate their effects and to present biofilter basics. Also, an educational video has been developed to help interested people get familiar with this technology.

Figure 1. (a)biofilter 1 (BF1) and biofilter 2(BF2) with front doors open; (b) biofilters with front doors closed; (c) media and water distribution system in BF2; (d) media and water distribution system in BF1; (e) shredded wood bark; (f) medium wood bark.

What have we learned?

(2) Supporting materials showing biofilter basics and its effects on reducing aerosol emissions are needed to encourage biofilter adoption,

(3) Field days are a good platform for both research and demonstrations of new techniques,

(4) Producer’ collaboration and full participation are very important to make the research a success.

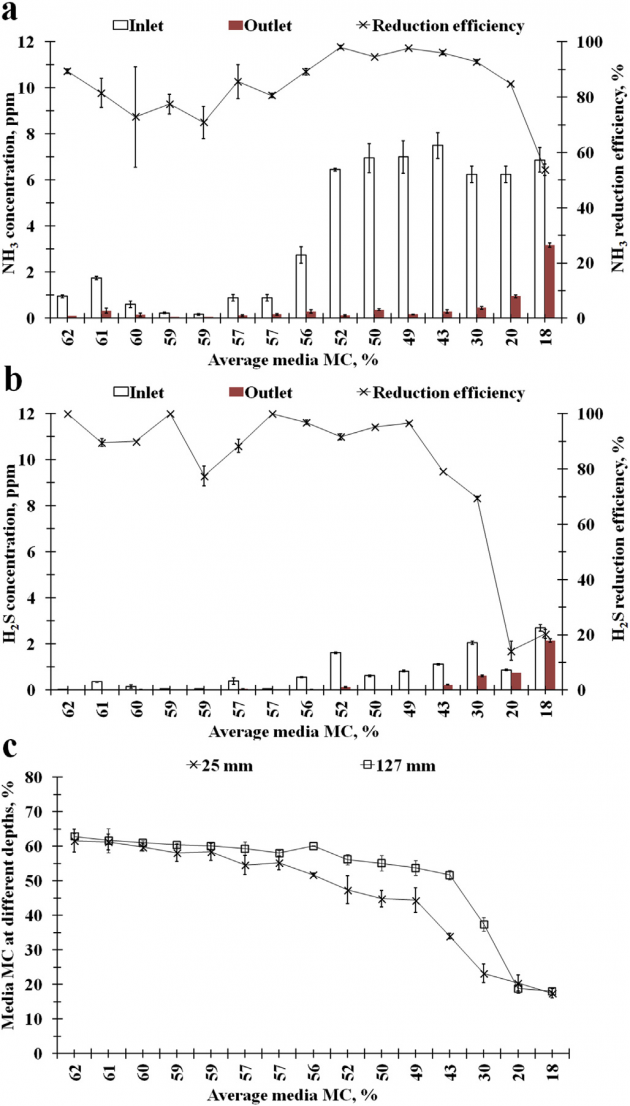

Figure 2. Odor and gas (NH3 and H2S) reduction efficiency and moisture distribution at different media depths of (a) biofilter 1 (BF1); (b) biofilter 2 (BF2).

Figure 3. Reduction efficiency for first stage of biofilter 2 (BF2) at different media moisture contents (MC) (a) NH3; (b) H2S; (c) moisture distribution at different media depths. Shredded wood bark (depth of 127 cm) was used and EBRT was 0.9-1.0 s.

Figure 4. Reduction efficiency for second stage of biofilter 2 (BF2) at different media moisture contents (MC) (a) NH3; (b) H2S; (c) moisture distribution at different media depths. Medium wood bark (depth of 254 cm) was used and EBRT was 1.8-2.0 s.

Future Plans

We will refine the developed educational videos and disseminate results from this study to our stakeholders.

Authors

Lide Chen, Waste Management Engineer and Assistant Professor, Biological and Agricultural Engineering Department, University of Idaho lchen@uidaho.edu

Gopi Krishna Kafle, Post-Doctoral Researcher; Howard Neibling, Extension Irrigation and Water Management Specialist and Associate Professor; B. Brian He, Professor, University of Idaho

Additional information

Contact Dr. Lide Chen at lchen@uidaho.edu for more information.

Acknowledgements

This project was partially funded by the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service through a Conservation Innovation Grant. The authors gratefully thank Mr. Dave Roper for his cooperative efforts during this research.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2015. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Seattle, WA. March 31-April 3, 2015. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

On-Farm Field Days as a Tool to Demonstrate Agricultural Waste Management Practices and Educate Producers

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Abstract

Teaching Best Management Practices (BMP) or introducing new agricultural waste management practices to livestock producers and farmers is a challenge. This poster describes a series of on-farm field days designed to deliver information and demonstrate on-site several waste management techniques, most of them well established in other parts of the country but sparsely used in Idaho. During these field days, Extension personnel presented each technique and offered written information on how to apply them. But without a doubt, presentations by the livestock producers and farmers who are already applying the techniques and hosted each field day at their farms was the main tool to spark interest and conversations with attendees.

Four field days were delivered in 2012 with more programmed for 2013. Demonstrated techniques reduce ammonia and odor emissions, increase nitrogen retention from manure, reduce run-off risks, and reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. Topics addressed on each field day were, a: Dairy manure collection and composting, 20 attendees. b: Dairy manure land application ten attendees. c: Grape vine prunings and dairy manure composting, 50 attendees. d: Mortality and offal on-farm composting, 40 attendees. In all cases farm owners and their managers presented and were available to answer attendees’ questions, sharing their experience, and opinions regarding the demonstrated practices. Many attendees expressed their interest and willingness to adopt some of the demonstrated practices. On-farm field days are an excellent tool to increase understanding and adoption of BMP and new technologies. Hearing experiences first hand from producers applying the techniques and being able to see them in action are excellent outreach tools. On-farm field days also fit the fast pace, busy schedule of modern producers who can later visit with Extension and other personnel if they need more details, information, and help on how to adopt the techniques they are interested in.

Why Hold Field Days on Ag Waste Management?

The dairy industry is the number one revenue commodity in Idaho. At the same time Idaho is ranked third in milk production in the nation. Idaho has more than 580,000 dairy cows distributed in 550 dairy operations (Idaho State Department of Agriculture 1/2013). The Magic Valley area in south-central Idaho hosts 54% of those dairies and 73% of all dairy cows in the state (Idaho Dairymen’s Association internal report, 2012). Odors from dairies and other animal feeding operations are a major issue in Idaho and across the country. In addition, the loss of ammonia from manures reduces the nutrient value of the manure and generates local and regional pollution. Dairy farmers of all sizes need more options on how to treat and dispose of the manure generated by their operations. Odor reductions, capture of nitrogen in dairy manure, reduction of greenhouse gases emissions, off-farm nutrients export, water quality protection, and reduction of their dairy operation’s environmental impact are some of the big challenges facing the dairy industry in Idaho and around the country. There are many Best Management Practices (BMP) that are proven to work on providing results related to the challenges mentioned before. Some of these practices are widely adopted in certain parts of the country or in other countries, with a lack of adoption by dairy producers and farmers in other parts of the country. This poster shows a series of Extension and research efforts designed to introduce and locally test proven BMP to dairy producers and crop farmers in southern Idaho in an effort to increase their adoption and incorporate those BMP as regular practices in Idaho agriculture. The four projects described were delivered in 2012 and some will continue in 2013.

What Did We Do?

To demonstrate and test BMP we chose to develop on-farm research projects to collect data and couple these projects with on-farm field days to demonstrate the applicability of the BMP in a real-world setting. Extension personnel developed the research and on-farm field days and did several presentations at each location. But without a doubt the stars during those field days were the dairy producers and farmers who hosted the research and demonstration events and who are already using or starting to use the techniques showcased. These pioneer producers are not only leading the way in using relatively new BMP in southern Idaho, they also share their experiences with other producers and with the academia so everybody around can learn from them. Topics addressed in each field day were, a: Dairy manure collection and composting, 20 attendees. b: Dairy manure land application, 10 attendees. c: Grapevine prunings and dairy manure composting, 50 attendees. d: Mortality and offal on-farm composting, 40 attendees.

|

On-farm manure collection and composting field day. |

Some highlights from each project are: a. The dairy manure collection and composting field day demonstrated the operation and use of a vacuum manure collection system and a compost turner. Dairy managers and machinery operators shared their experiences, benefits and challenges related to the use of these two technologies. During the field day attendees also visited the whole manure management system of the dairy and were able to observe diverse manure management techniques. As a result of this project Extension personnel determined the necessity of generating educational programs for compost and manure management operators for dairy employees. A composting school in Spanish and English proposal was presented and a grant was obtained to develop and deliver them in 2013.

b. The dairy manure land application field day featured the demonstration of a floating manure storage pond mixer and pump, and a drag hose manure injection system. We also showed an injection tank that wasn’t operated during the demonstration. The floating pond mixer serves as lagoon mixer and pump. It mixes and pumps the manure through the drag hose system to the subsurface injector. This system dramatically reduces the time required to land apply liquid and slurried manures. It also significantly reduces ammonia and odor emissions to near background levels, as well as avoids runoff after applications. This project included research of emissions on the manure injection sites (see Chen L., et al. in this conference proceedings).

|

Demonstrating dairy manure subsurface injection using a drag hose system. |

c. The grapevine prunings and dairy manure composting project involves research on the implications of increasing the carbon content of dairy manures using grapevine prunings and other carbon sources to retain more nitrogen in the compost, and how it varies among three diferent composting techniques. This project includes two field days, one during the project (2012), and another one at the end of it in 2013. The demonstration includes how to compost using mechanically turned windrows (common in Idaho), passive aerated, and forced aerated windrows (both very rarely used in Idaho). Another novelty in this project is that it aims to bring together dairy producers and fruit & crop producers, or landscaping insustry so they can combine their waste streams to produce a better compost and to reduce the environmental impact of each operation. Several producers of the diverse audience who attended showed interest in adopting some of the composting techniques presented during the field day.

|

On-farm composting methods featuring grape vine prunings and dairy manure compost |

d. The mortality and offal on-farm composting project was located at a diversified sheep farm that includes sheep and goat dairy and cheese plant, meat lambs, and chickens. A forced aerated composting box was used to compost lamb offal, hives, lamb and chicken mortalities, and whey from the cheese plant. A very diversified audience attended the field day and the composting system generated a lot of interest. The farm owner was so pleased with the system that she created a second composter with materials she had on-hand to increase her composting capabilities and compost all year round. The producer stopped disposing of lamb offal, hives, and mortalities at the local landfill.

What Have We Learned?

On-farm field days are a great tool to demonstrate and encourage the application of otherwise seldom applied techniques. They also can serve a dual purpose of demonstration and research, allowing for quality data collection if designed properly. Farmers’ collaboration and full participation during all phases of the project is paramount and pays off by having a very enthusiastic and collaborative partner. Identiying progressive and pioneer producers that are already applying new BMP or are willing to take the risk is very important to develop this kind of on-farm experience. In general these individuals are also willing to share their knowledge, experience, and results with others to increase the adoption of such techiques. Having a producer hosting and presenting during the field day, at their facilities (as opposed to a dedicated research facility) generates great enthusiasm from other producers and helps to “break the ice” and bring everybody to a friendly conversation and exchange of ideas if properly facilitated.

Future Plans

On both projects, a. manure collection and composting and b. manure injection we will generate a series of videos to demonstrate the proper application of BMP, and educational printed material will also be published. Project c. grape prunings and manure composting is still going on and we will finish collecting data by mid 2013. A second field day will be offered and videos and printed educational material will be developed. Project d. will see an expansion with a mortality composter for dairy calves being installed at a dairy, and with a field day following after the first compost batch is ready. Additional programs are in the works; these programs incorporate the on-farm demonstration and research dual purpose and have high participation from the involved producers.

Authors

Mario E. de Haro-Marti, Extension Educator, Gooding County Extension Office, University of Idaho Extension. mdeharo@uidaho.edu

Lide Chen, Waste Management Engineer

Howard Neibling, Extension Irrigation and Water Management Specialist

Mireille Chahine, Extension Dairy Specialist

Wilson Gray, District Extension Economist

Tony McCammon, Extension Educator

Ariel Agenbroad, Extension Educator

Sai Krishna Reddy Yadanaparthi, Graduate student

James Eells, Research Assistant. University of Idaho Extension.

Acknowledgements

Projects a. and b. were supported by a USDA-NRCS Conservation and Innovation Grant (CIG). Project c. was supported by a USDA-NRCS Idaho CIG. Project d. was supported by a University of Idaho USDA-SARE mini grant. We also want to thank Jennifer Miller at the Northwest Center for Alternatives to Pesticides for her help and support with projects c. and d. Finally, we want to thank all producers involved in these projects for their support and openess to work with us, and for their innovative spirit.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Diet, Tillage and Soil Moisture Effects on Odorous Emissions Following Land Application of Beef Manure

Figure1. Gas sampling equipment used during the study. |

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Abstract

Little information is currently available concerning odor emissions following land application of beef cattle manure. This study was conducted to measure the effects of diet, tillage, and time following land application of beef cattle manure on the emission of volatile organic compounds (VOC).

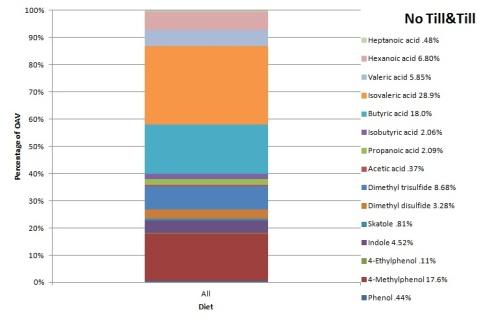

Each of the experimental treatments which included tillage (broadcast or disked) and diet (0, 10, or 30% wet distillers grain (WDGS)) were replicated twice. A 5-m tandem finishing disc was used to incorporate the manure to a depth of approximately 8 cm. Small plots (0.75 m x 2.0 m) were constructed using 20 cm-wide sheet metal frames. A flux chamber was used to obtain air samples within the small plots at 0, 1, 2, 6, and 23 hours following manure application. The flux of fifteen VOC including fatty acids, aromatic compounds, and sulfur containing compounds were measured. Based on odor threshold, isolavleric acid, butyric acid, and 4-methylphenol provided 28.9%, 18.0%, and 17.7%, respectively, of the total measured odor activity. Heptanic acid, acetic acid, skatole, 4-methyphenol, and phenol each contributed less than 1% of the total odor activity. Dimethy disulfide (DMDS) and dimethyl trisulfide were the only measured constituents that were significantly influenced by diet.

DMDS values were significantly greater for the manure derived from the 30% WDGS diet than the other manure sources. No significant differences in DMDS values were found for manure derived from diets containing 0% and 10% WDGS. Tillage did not significantly affect any of the measured VOC compounds. Each of the VOC was significantly influenced by the length of time that had expired following land application. In general, the smallest VOC measurements were obtained at the 23 hour sampling interval. Diet, tillage, and time following application should each be considered when estimating VOC emissions following land application of beef cattle manure.

Why Study Factors Affecting Manure Application Odors?

Measure the effects of diet, tillage and soil moisture on odor emissions follow land applied beef manure.

Figure 2. Relative contribution of odorant to the total odor activity. |

What Did We Do?

Twelve plots were established across a hill slope. Treatments were tillage (broadcast or disked) and diet (0%, 10%, or 30% WDGS). Beef manure was applied at 151 kg N ha-1 yr-1. Gas samples were collected using small wind tunnels and analyzed using a TD-GC-MS. (Fig. 1). VOC samples were collected at 0, 1, 2, 6, and 23 hours following manure application. A single application of water was applied and the gas measurement procedure was repeated. The effects of tillage, diet, test interval, and the sample collection time on VOC measurements were determined using ANOVA (SAS Institute, 2011).

What Have We Learned?

Isovaleric acid, butyric acid, and 4-methylphenol accounted for 28.9%, 18.0%, and 17.7%, respectively of the total odor activity (Fig. 2). Dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) and dimethyl trisulfide (DMTS) emissions were significantly increased by the 30 % WDGS diet. The flux increase for DMDS was over 4 times greater for the 30% WDGS diets. Tillage did not significantly affect any of the measured VOC compounds. The largest propionic, isobutric, butyric, isovaleric, and valeric acid measurements occurred with no-tillage under dry condition (Fig. 3A-E). Generally, measured values for these constituents were significantly greater at the 0, 1, 2, and 6 hour sampling intervals than at the 23 hour interval (Fig. 3A-E). The larger emissions for no-till, dry conditions may be due to the drying effect resulting when the manure was broadcast on the surface. As the manure begins to dry, the water soluble VOCs are released from solution. The tilled and wet conditions would reduce its release of VOC due to the increased moisture conditions.

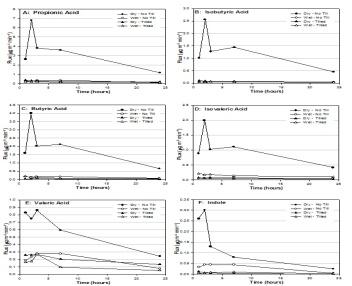

Figure 3. Flux values for propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric , valeric acid and indole as affected by tillage, soil moisture, and time. |

Future Plans

Additional studies are planned to quantify the moisture and temperature effect on odorous emissions.

Authors

Bryan L. Woodbury, Research Agricultural Engineer, USDA-ARS, bryan.woodbury@ars.usda.gov

John E. Gilley, Research Agricultural Engineer, USDA-ARS;

David B. Parker, Professor and Director, Commercial Core Laboratory, West Texas A&M University;

David B. Marx, Professor Statistics, University of Nebraska-Lincoln;

Roger A. Eigenberg, Research Agricultural Engineer, USDA-ARS

Additional Information

http://www.ars.usda.gov/Main/docs.htm?docid=2538

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Todd Boman, Sue Wise, Charlie Hinds and Zach Wacker for their invaluable help on making this project a success.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Inhibition Of Total Gas Production, Methane, Hydrogen Sulfide, And Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria From In Vitro Stored Swine Manure Using Condensed Tannins

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Abstract

Management practices from large-scale swine production facilities have resulted in the increased collection and storage of manure for off-season fertilization use. Odor produced during storage has increased the tension among rural neighbors and among urban and rural residents, and greenhouse gas emissions may contribute to climate change. Production of these compounds from stored manure is the result of microbial activity of the anaerobic bacterial populations present during storage. We have been studying the bacterial populations of stored manure to develop methods to reduce bacterial metabolic activity and production of gaseous emissions, including the toxic odorant hydrogen sulfide produced by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Quebracho and other condensed tannins were tested for effects on total gas, hydrogen sulfide, and methane production and levels of sulfate-reducing bacteria in in vitro swine manure slurries. Quebracho condensed tannins were found to be most effective of tannins tested, and total gas, hydrogen sulfide, and methane production were all inhibited by greater than 90% from in vitro manure slurries. The inhibition was maintained for at least 28 days. Total bacterial numbers in the manure were reduced significantly following addition of quebracho tannins, as were sulfate-reducing bacteria. These results indicate that the condensed tannins are eliciting a collective effect on the bacterial population, and the addition of quebracho tannins to stored swine manure may reduce odorous and greenhouse gas emissions.

Why Would We Want to Inhibit Gas Production of Stored Manure?

Develop methods for reducing odor and emissions from stored swine manure.

What Did We Do?

Tested the effects of addition of condensed tannins to in vitro swine manure slurries on production of total gas, hydrogen sulfide, methane, and on the levels of hydrogen sulfide-producing sulfate reducing bacteria.

What Have We Learned?

Addition of condensed tannins to in vitro swine manure slurries reduces production of total gas, with quebracho condensed tannins being the most effective. 0.5% w/v Quebracho condensed tannins reduced total gas, hydrogen sulfide, and methane by at least 90% over a minimum of 28 days. Levels of sulfate reducing bacterial were also significantly reduced by addition of the tannns. This technique should assist swine producers in lowering emission and odors from stored manure.

Future Plans

We are interested in scaling up the testing to on-farm sites and also testing the tannins for reducing foaming from manure storage pits.

Authors

Terence R. Whitehead, Research Microbiologist, USDA-ARS-National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, IL 61604, terry.whitehead@ars.usda.gov

Cheryl Spence, USDA-ARS-National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, IL 61604

Michael A. Cotta, USDA-ARS-National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, IL 61604

Additional Information

Whitehead, T.R., Spence, C., and Cotta, M.A. Inhibition of Hydrogen Sulfide, Methane and Total Gas Production and Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in In Vitro Swine Manure Slurries by Tannins, with Focus on Condensed Quebracho Tannins. (2012) Appl. Microbiol. Biotech. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-012-4562-6/fulltext.html

Development and Comparison of SYBR Green Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assays for Detection and Enumeration of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in Stored Swine Manure. (2008) J. Appl. Microbiol. 105: 2143-2152. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03900.x/pdf

USDA-ARS-NCAUR Bioenergy Research Unit Home Page: http://ars.usda.gov/main/site_main.htm?modecode=36-20-61-00

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Vegetative Environmental Buffers (VEBs) for Mitigating Air Emissions from Livestock Facilities: A Review

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Abstract

Air emissions from livestock facilities are receiving increasing attention because of concerns related to nuisance, health and upcoming air quality regulations. Vegetative buffers have been proposed as a potential cost effective mitigation strategy to reduce dust, odor and other air pollutants from farm and can be an important part of air quality management plan. However, the effectiveness of vegetative buffers in mitigating air emissions seems to be site specific and can be affected by many factors. This study aims to provide a thorough literature review on the performance of vegetative buffers in mitigating air emissions, to investigate critical factors, and to identify research gaps. The results will be used as basis for planning future wind tunnel and field studies. The ultimate objective is to develop general guidance for vegetative buffer design and to demonstrate the variety and effectiveness of vegetative buffers for mitigating air emissions from livestock facilities.

Why Study Trees As a Potential Odor Management Strategy?

Vegetative environmental buffers (VEBs) have been proposed as a mitigation strategy for air emissions from livestock facilities. Survey indicated producers are interested in using VEBs for odor management. But lack of information on performance, cost and technical guidelines are barriers to adoption of VEBs.

What Did We Do?

Review published research on effectiveness of VEBs for mitigating air emissions from livestock facilities.

What Have We Learned?

VEBs have been examined primarily in swine and poultry farms. Iowa, Pennsylvania and Delaware are actively involved in research and implementation of VEBs for livestock farms. VEBs are potential cost effective strategy for reducing dust (by up to 56%), odor (by up to 68%), NH3 (by up to 54%) and H2S (by up to 85%) from farms, although effectiveness and costs are highly variable and depend on site specific design. Most effective reduction occurs just beyond the VEBs. Wind tunnel simulation on barriers at roadside showed that percentage reduction of pollutants decreasing with downwind distance, and they are generally below 50% beyond 15 barrier height.

|

Mitigation Mechanisms of VEBs |

Future Plans

Measure the concentrations of multiple air emission constituents at various distance from a swine facility with and without the presence of a VEB under various weather conditions; determine the effectiveness of the VEB under various design parameters (height and depth) and evaluate how height and depth of the VEB will affect the mitigation effectiveness; develop design suggestions and best management procedures to utilize a VEB in order to maximize effectiveness with limited costs.

Authors

Zifei Liu, Assistant Professor, Kansas State University. Zifeiliu@ksu.edu

Ronaldo Maghirang, Pat Murphy, Kansas State University

Additional Information

http://www.bae.ksu.edu/~zifeiliu/

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Model of a Successful Regulatory-Industry Partnership to Address Air Emissions from Dairy Operations in Yakima, WA

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Why Is It Important for Industry and Regulators to Work Together?

The community in the Yakima Region of Washington State has raised concerns over the potential adverse effects of air emissions from dairy operations. To address these concerns, the Yakima Regional Clean Air Agency (YRCAA) proposed a policy process in October 2010 to control and mitigate emissions through implementation of site-specific best management practices (BMPs) on dairy operations. Absent a lack of reliable methodologies for estimating emissions from dairies, the YRCAA enrolled experts and scientists to help create tools that could be used for estimation of emissions from dairy operations. The assessment of BMPs aimed at mitigating air emissions from dairies was also included to determine their effect on the character, amount, and dispersion of specific air pollutants. This project assessed the effect of voluntary verses policy driven action on the dairy industry, community, and environmental impacts of air emissions from dairy operations.

What Did We Do?

The Yakima Regional Clean Air Agency (YRCAA) proposed a draft policy in October 2010 to control and mitigate emissions through implementation of site-specific best management practices (BMPs) on dairy operations. To validate the policy, a “Pilot Research Project” was launched in February 2011 to gather information for one year to test the feasibility of implementing and determining policy effectiveness. Twelve operations, representing ~40% of the estimated regional cow numbers, volunteered to participate.

A description of proven BMPs and a BMP selection-guide were created to help producers develop site-specific Air Quality Management Plans (AQMP). Each AQMP identified, systematically, specific BMPs to mitigate emissions from each area of the dairy system (nutrition, feed management, milk parlor, housing-drylot, housing-freestall, grazing, manure management, land application, other) based on effectiveness, practicality and economics. The pollutants addressed in each AQMP included ammonia, nitrous oxide, hydrogen sulfide, volatile organic compounds, odor, particulate matter, oxides of nitrogen, and methane. A universal score-sheet was created to assess implementation of BMPs at each dairy. The YRCAA inspectors were trained to evaluate, score, and record BMP implementation. A whole-farm score was generated during each visit, which identified areas of improvement to be addressed.

The process was very unique in that the dairy industry took a proactive role and actively participated. Using science and air quality experts to create and validate the evaluation tools and process also brought authority to the process. The policy was revised based on information collected from the pilot project and was adopted in February 2012. To date, 22 operations, representing 57% of total cow numbers in the Yakima Region, are enrolled.

What Have We Learned?

The voluntary approach used during the pilot project phase of the policy was very effective in enrolling the dairy community. Producers stepped up to volunteer and cooperatively participate in an unknown process. Even though they were very robust and integrated a large amount of scientific information, the emission assessment tools created as an outcome of the pilot project were very user friendly and easy to interpret by planners and producers. The air quality BMP assessment tool is currently being evaluated for use by other agencies and institutions.

Future Plans

The YRCAA has entered into phase two of the policy process and are now mandating that dairies participate in the air quality assessment. Starting in March 2013, all dairy operations in the Yakima basin will be either voluntarily or mandatorily inspected and assessed for air quality improvements. This provides an opportunity to compare voluntary and mandatory policy processes. The long-term impact of the process is yet unknown.

Authors

Nichole M. Embertson, Ph.D., Nutrient Management Specialist, Whatcom Conservation District, Lynden, WA, nembertson@whatcomcd.org

Gary Pruitt, Executive Director, Yakima Regional Clean Air Agency Air, Yakima, WA

Hasan Tahat, Engineering and Planning Supervisor, Yakima Regional Clean Air Agency Air, Yakima, WA

Pius Ndegwa, Biological and Systems Engineering, Washington State University, Pullman, WA

Additional Information

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.