Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

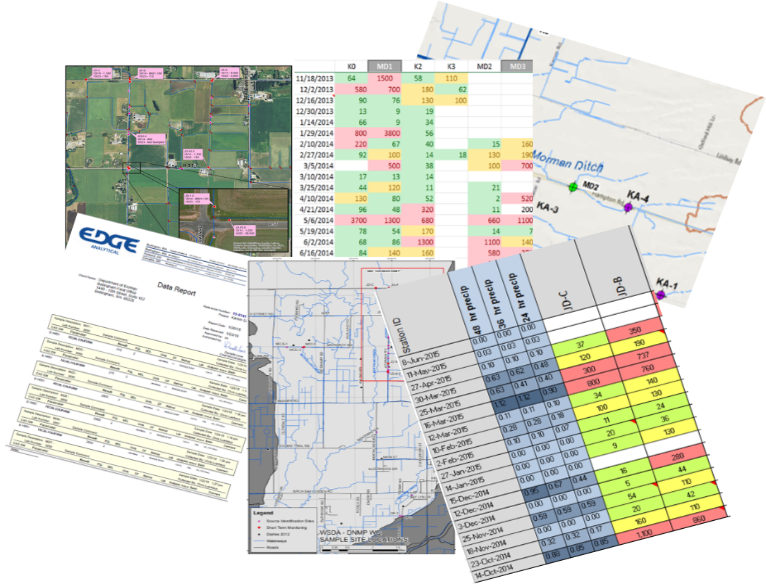

In 2015, Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) partnered with local and state agencies to help identify potential sources of fecal coliform bacteria that were impacting shellfish beds in northwest Washington. WSDA and Pollution Identification and Correction (PIC) program partners began collecting ambient, as well as rain-driven, source identification water samples. Large watersheds with multiple sub-basins, changing weather and field conditions, and recent nutrient applications, meant new sites were added almost daily. The increased sampling created an avalanche of new data. With this data, we needed to figure out how to share it in a way that was timely, clear and could motivate change.

Conveying complex water quality results to a broad audience can be challenging. Previously, water quality data would be shared with the public and partners through spreadsheets or graphs via email, meetings or quarterly updates. However, the data that was being shared was often too late or too overwhelming to link locations, weather or field conditions to water quality. Even though plenty of data was available, it was difficult for it to have meaningful context to the general public.

Ease of access to results can help inform landowners of hot spots near their home, it can link recent weather and their own land management practices with water quality, as well as inform and influence decision-making.

What Did We Do?

Using basic GIS tools we created an interactive map, to share recent water quality results. The map is available on smartphones, tablets and personal computers, displaying near-real-time results from multiple agencies. Viewers can access the map 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

We have noticed incre ased engagement from our dairy producers, with many checking the results map regularly for updates. The map is symbolized with graduated stop light symbology, with poor water quality shown in red and good in green. If they see a red dot or “hot spot” in their neighborhood they may stop us on the street, send an email, or call with ideas or observations of what they believe may have influenced water quality. It has opened the door to conversations and partnerships in identifying and correcting possible influences from their farm.

ased engagement from our dairy producers, with many checking the results map regularly for updates. The map is symbolized with graduated stop light symbology, with poor water quality shown in red and good in green. If they see a red dot or “hot spot” in their neighborhood they may stop us on the street, send an email, or call with ideas or observations of what they believe may have influenced water quality. It has opened the door to conversations and partnerships in identifying and correcting possible influences from their farm.

The map also contains historic results data for each site, which can show changes in water quality. It allows the viewer to evaluate if the results are the norm or an anomaly. “Are high results after a rainfall event or when my animals are on that pasture?”

The online map has also increased engagement with our Canadian neighbors to the north. By collecting samples at the US/Canadian border we have been able to map streams where elevated bacteria levels come across the border. This has created an opportunity to partner with our Canadian counterparts to continue to identify and correct sources.

What Have We Learned?

You do not need to be a GIS professional to create an app like this for your organization. Learning the system and fine-tuning the web application can take some time, but it is well worth the investment. GIS skills derived from this project have proven invaluable as the app transfers to other areas of non-point work. The web application has created great efficiencies in collaboration, allowing field staff to quickly evaluate water quality trends in order to spend their time where it is most needed. The application has also provided transparency to the public regarding our field work, demonstrating why we are sampling particular areas.

From producer surveys, we have learned that viewers prefer a one-stop portal for information. Viewers are less concerned about what agency collected the data as they are interested in what the data says. This includes recent, as well as historical water quality data, field observations; such as wildlife or livestock presence or other potential sources. Also, a brief weekly overview of conditions, observations and/or trends has been requested to provide additional context.

Future Plans

The ease and efficiency of the mobile mapping and data sharing has opened the door to other collaborative projects. Currently we are developing a “Nutrient Tracker” application that allows all PIC partners to easily update a map from the field. The map allows the user to log recent field applications of manure. Using polygons to draw the area on the field, staff can note the date nutrients were identified, type of application, proximity to surface water, if it was a low-, medium- or high-risk application, if follow-up is warranted, and what agency would be the lead contact. This is a helpful tool in learning how producers utilize nutrients, to refer properties of concern to the appropriate agency, and to evaluate recent water quality results against known applications.

Developing another outreach tool, WSDA is collecting 5 years of fall soil nitrate tests from all dairy fields in Washington State. The goal is to create a visual representation of soil data, to demonstrate to producers how nitrate levels on fields have changed from year to year, and to easily identify areas that need to be re-evaluated when making nutrient application decisions.

As part of a collaborative Pollution Identification and Correction (PIC) group, we would like to create a “Story Map” that details the current situation, why it is a concern, explain potential sources and what steps can be taken at an individual level to make a difference. A map that visually demonstrates where the watersheds are and how local neighborhoods really do connect to people 7 miles downstream. An interactive map that not only shows sampling locations, but allows the viewer to drill down deeper for more information about the focus areas, such as pop-ups that explain what fecal coliform bacteria are and what factors can increase bacteria levels. We envision a multi-layer map that includes 24-hour rainfall, river rise, and shellfish bed closures. This interactive map will also share success stories as well as on-going efforts.

Author

Kerri Love, Dairy Nutrient Inspector, Dairy Nutrient Management Program, Washington State Department of Agriculture

Additional Information

Results Map Link: http://arcg.is/1Q9tF48

Washington Shellfish Initiative: http://www.governor.wa.gov/issues/issues/energy-environment/shellfish

Mobile Mapping Technology presentation by Michael Isensee, 2016 National CAFO Roundtable

Sharing the Data: Interactive Maps Provide Rapid Feedback on Recent Water Quality and Incite Change by Educating the Public, Kyrre Flege, Washington State Department of Agriculture and Jessica Kirkpatrick, Washington State Department of Ecology, 2016 National Non-Point Source Monitoring Workshop

Whatcom County PIC Program: http://www.whatcomcounty.us/1072/Water-Quality

Skagit County, Clean Samish Initiative: https://www.skagitcounty.net/Departments/PublicWorksCleanWater/cleansamish.htm

Lower Stillguamish PIC Program: http://snohomishcountywa.gov/3344/Lower-Stilly-PIC-Program

GIS Web Applications: http://doc.arcgis.com/en/web-appbuilder/

Acknowledgements

The web application was a collaborative project developed by Kyrre Flege, Washington State Department of Agriculture and Jessica Kirkpatrick, Washington State Department of Ecology.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2017. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Cary, NC. April 18-21, 2017. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Agricultural Library. Results show that the greatest levels of methane produced on a farm come from enteric emissions of the cow and changes in the diet, digestion and genetics of the cow can reduce those emissions. Another significant source of methane—manure production, storage and management—can be substantially reduced through manure management practices, particularly when it is processed through an anaerobic digester. Changes in timing of nitrogen application and use of cover crops practices are found to improve nitrogen efficiency and reduce losses from the field.

Agricultural Library. Results show that the greatest levels of methane produced on a farm come from enteric emissions of the cow and changes in the diet, digestion and genetics of the cow can reduce those emissions. Another significant source of methane—manure production, storage and management—can be substantially reduced through manure management practices, particularly when it is processed through an anaerobic digester. Changes in timing of nitrogen application and use of cover crops practices are found to improve nitrogen efficiency and reduce losses from the field.