Purpose

Dairy farmers in Washington state have been under significant pressure to reduce their carbon footprint in recent years. Dairy cooperative sustainability initiatives such as achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 have left many producers wondering what will be required of them to help their cooperatives meet this goal. Coupled with regulatory pressures to report on their greenhouse gas emissions and the threat of regulation to reduce them, uncertainty remains for producers around the types of climate-smart practices that will enable them to reduce their carbon footprint while remaining economically viable.

Without a thorough understanding of the costs and risks, pressures, or requirements to implement climate-smart practices may inadvertently drive consolidation and the accelerated loss of small to medium sized farms.

What Did We Do?

Utilizing Washington state dairy facility data, I conducted an economic cost benefit analysis of two climate-smart practices that capture GHGs from anaerobic storage: anaerobic digestors and the covered lagoon and flare system and the size of operation needed to implement both practices based on current and historic market conditions and technology costs. Private and public investment in climate-smart practices can have a substantial impact on whether they are economically feasible for producers to implement. I considered the impacts of various levels of cost-share on the size of farm able to adopt the technology based on several economic indicators.

What Have We Learned?

Most dairy farms cannot simply raise their prices to offset the costs of climate-smart practices, therefore it is critical to understand the broad economic impacts of imposing emissions reductions mandates. With consolidation being a well-documented trend across dairy farms in the United States, it is possible that climate regulations will only further exacerbate this trend due to the high capital costs and market risk associated with climate-smart farming that only facilities of scale can take on.

Future Plans

I am actively assisting research right now in Washington state with university and private researchers into dairy farm carbon intensities, across various farm sizes and facility types. An overview of this research may be available by Summer of 2025. Once this work is completed, we will have a better understanding of overall farm emissions and what climate-smart practices may be necessary for farms to implement to help achieve cooperative net zero targets.

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Nina Gibson, Agricultural Economist and Policy Specialist, Washington State Department of Agriculture, KGibson@agr.wa.gov

Additional Information

Link to Podcast I hosted, the Carbon and Cow$ Podcast, which covers the risks and opportunities associated with carbon markets for dairy and livestock producers: https://csanr.wsu.edu/program-areas/climate-friendly-farming/carbon-and-cows-podcast/

Link to my program’s homepage at WSDA: https://agr.wa.gov/manure

My Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/nina-gibson-b482a8119/

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7–11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

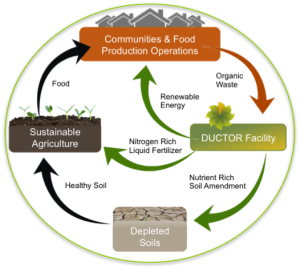

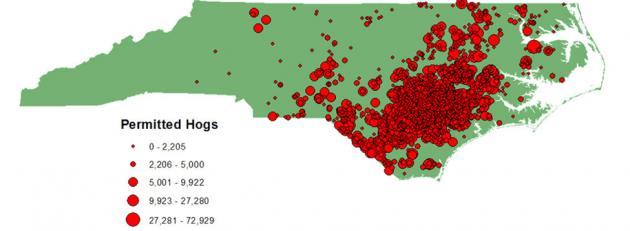

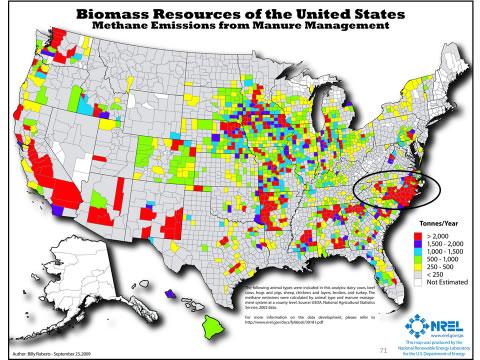

forward-thinking farmers have learned that their waste is valuable for supplying renewable energy, it has been unfortunately difficult for an individual farmer to implement and manage advanced value recovery systems primarily due to costs of scale. Rather, it seems, success may be easier achieved through the aggregation of these products from several farms and through the collaborative efforts of project developers, product offtakers, and policy. A shining example of such aggregation and collaboration can be observed from the Optima-KV swine waste to pipeline renewable gas project, located in eastern North Carolina in an area of dense swine farm population.

forward-thinking farmers have learned that their waste is valuable for supplying renewable energy, it has been unfortunately difficult for an individual farmer to implement and manage advanced value recovery systems primarily due to costs of scale. Rather, it seems, success may be easier achieved through the aggregation of these products from several farms and through the collaborative efforts of project developers, product offtakers, and policy. A shining example of such aggregation and collaboration can be observed from the Optima-KV swine waste to pipeline renewable gas project, located in eastern North Carolina in an area of dense swine farm population. required, which presented challenges of negotiating multiple utility connections and agreements. This learning curve was steepened as, at the time of the inception of Optima KV, the state of North Carolina lacked formal pipeline injection standards, so the final required quality and manner of gas upgrading was established through the development of the project.

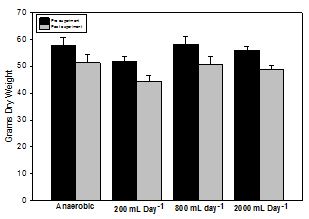

required, which presented challenges of negotiating multiple utility connections and agreements. This learning curve was steepened as, at the time of the inception of Optima KV, the state of North Carolina lacked formal pipeline injection standards, so the final required quality and manner of gas upgrading was established through the development of the project. Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.