To be sustainable, producers need to conserve energy while still maintaining or improving their facilities and the lives of the animals they house. This presentation was originally broadcast on December 15, 2023. Continue reading “Energy Conservation in Livestock and Poultry Operations”

Energy Consumption in Commercial Midwest Dairy Barns

Consumer interest and concern is growing in regards to sustainability of livestock production systems. Demand for reduced carbon emissions within agricultural systems has been growing along with increasing demand for food. Baseline fossil fuel consumption within agricultural systems, including dairy production, is scarce. Therefore, there is a need to discern where and how fossil energy is being used within dairy production systems. Determining baseline energy use is the first step in investigating the demand for a reduced carbon footprint within dairy production systems. The objective of this study was to measure total electricity use and determine specific areas of high energy consumption in commercial dairy barns located in the Upper Midwest of the United States.

What did we do?

Four commercial dairy barns representative of typical Midwest dairy farms and located in west central Minnesota were evaluated in the study. The dairy farms were: 1) a 9,500 cow cross-ventilated barn with a rotary milking parlor (Farm A), 2) a 300 cow naturally-ventilated barn with stirring fans for air movement and 6 automatic milking systems (Farm B), 3) a 200 cow naturally-ventilated barn with stirring fans for air movement and a parabone milking parlor (Farm C), and 4) a 400 cow naturally-ventilated barn with stirring fans for air movement and a parallel milking parlor (Farm D).

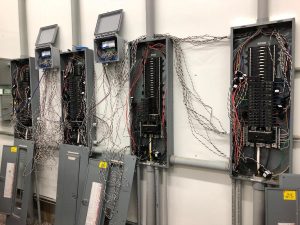

Electricity use was monitored from July 2018 to December 2018 with a goal of collecting two years of total energy usage. Two-hundred ninety-two electric loads across the four farms were monitored on the farm side of the electric utility meter to evaluate areas of highest energy usage (Figure 1). Some of the monitored electric loads included freestall barn fans, water heaters, compressors, chillers, manure pumps, and pressure washers. The electric loads were monitored by data loggers (eGauge, Boulder, CO) and electric current sensors at the circuit panels. Electrical use data (kWh) of each load were collected and analyzed on a monthly basis. In addition, monthly inventory of cows on farm, cows milked per day, and milk production was recorded. Bulk tank production records (milk, fat percentage, protein percentage, and somatic cell count) were also recorded.

What have we learned?

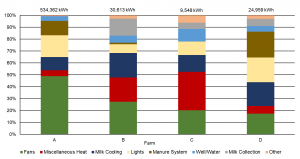

Based on preliminary results, fans were the largest electrical load across all four dairy farms. Fan usage during the summer ranged from 36 to 59% of the total electricity measured (Figure 2). Regular maintenance, proper control settings, design, sizing, location, selecting energy efficient fans and motors, and other factors all could influence the efficiency of these ventilation/cooling systems. Farms B, C, and D had greater electricity usage across all months for milk cooling (compressors and chillers) than Farm A. This is likely due to the fact that Farm A does not utilize bulk tanks to store milk, but instead, milk is directly loaded onto bulk milk trucks. Lighting use ranged from 7 to 21% of the total electricity use measured across the four farms, which suggests there is potential to reduce energy usage by upgrading to more efficient lighting systems such as LEDs. For heating, energy usage includes water heating, heating units in the milking parlor or work rooms, waterer heating elements, and generator engine block heaters. Average monthly heating use ranged from 5% of electricity used in Farm A to 32% of electricity used in Farm C.

Future plans

Based on the preliminary analysis, clean energy alternatives and energy-optimized farms will be modeled as clean energy alternatives for Minnesota dairy facilities. An economic analysis will also be conducted on the clean energy alternatives and farms. Potential on-site renewable electric generation may supply some or the entire electric load allowing the buildings to approach net-zero (producing as much energy as is used).

The results of this study provide recent energy usage for farm energy benchmarks, agricultural energy policy, economic evaluations, and further research into dairy farm energy studies. The data will also be useful to producers who are searching for areas for reduced energy usage in their own production systems. Improving the efficiency of electrical components in dairy operations could provide opportunities to improve the carbon footprint of dairy production systems.

Authors

Kirsten Sharpe, Animal Science Graduate Research Assistant, West Central Research and Outreach Center (WCROC), Morris, MN, sharp200@umn.edu

Bradley J. Heins, Associate Professor, Dairy Management, WCROC, Morris, MN

Eric Buchanan, Renewable Energy Scientist, WCROC, Morris, MN

Michael Cotter, Renewable Energy Researcher, WCROC, Morris, MN

Michael Reese, Director of Renewable Energy, WCROC, Morris, MN

Additional information

The West Central Research and Outreach Center (WCROC) has developed a Dairy Energy Efficiency Decision Tool to help provide producers a way to estimate possible energy and costs savings from equipment efficiency upgrades. The tool can be used to evaluate areas of a dairy farm that may provide the best return on investment for energy usage. Furthermore, a guidebook has been developed for Optimizing Energy Systems for Midwest Dairy Production. This guidebook provides additional information about energy usage issues as well as a decision tool. More information may be found at https://wcroc.cfans.umn.edu/energy-dairy

Acknowledgements

The funding for this project was provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR).

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2019. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Minneapolis, MN. April 22-26, 2019. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Frank Wideman

Frank Wideman is a Natural Resources Engineering Specialist with the University of Missouri Extension. He specializes in natural resource management, water quality, farm and home energy and emerging technologies. He includes GIS, GPS, and Remote Sensing in all those areas. He also utilizes distance education, social media, and community resource management to develop these programs. He is currently serving as an eXtension Question Wrangler along with his duties for University of Missouri. Frank has a B.S. & M.S. in Agricultural Engineering, both from University of Missouri.

Currently, Frank is working on projects that include natural resource management and energy conservation and alternative energy sources. His emphasis is on using the emerging technologies to solve local community issues and needs with science based information.

Contact Information:

Email: widemanf@missouri.edu

phone: 573-547-4504

Environmental Footprints of Beef Produced At the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Why Study the Environmental Footprint of Beef?

As a major contributor in food production, beef production provides a major service to our economy that must be maintained. Production of cattle and the associated feed crops required also impact our environment, and this impact is not well understood. Several studies have determined the carbon footprint of beef, but there are other environmental impacts that must be considered such as fossil energy use, water use, and reactive nitrogen loss to the environment. Because of the large amount of data available to support model evaluation, production systems of the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center were simulated with the Integrated Farm System Model for the purpose of evaluating the environmental impact of the beef cattle produced.

What Did We Do?

The environmental footprints of beef produced at the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center (MARC) in Clay Center, Nebraska were determined with the objective of quantifying improvements achieved over the past 40 years. Relevant information for MARC operations was used to establish parameters representing their production system with the Integrated Farm System Model. The MARC farm, cow calf and feedlot operations were each simulated over recent historical weather to evaluate performance, environmental impact and economics. The current farm operation included 2,078 acres of alfalfa and 2,865 acres of corn to produce feed predominately for the beef herd of 5,500 cows, 1200 replacement heifers and 3,724 cattle finished per year. Spring and fall cow calf herds were fed on 24,000 acres of pastureland supplemented through the winter with hay and silage produced by the farm operation. Feedlot cattle were backgrounded 3 mo on hay and silage and finished over 7 mo on a diet high in corn grain and wet distiller’s grain.

What Have We Learned?

Model simulated predictions for weather year 2011 were within 1% of actual records for feed production and use, energy use, and production costs. A 25-year simulation of their current production system gave a carbon footprint of 10.9 lb of CO2 equivalent units per lb body weight (BW) sold, and the energy required to produce that beef was 11,400 Btu/lb BW. The total water required was 2,560 gallon/lb BW sold, and the water footprint excluding that obtained through precipitation was 335 gallon/lb BW. Reactive N loss was 0.09 lb/lb BW, and the simulated total cost of producing their beef was $0.96/lb BW sold. Simulation of the production practices of 2005 indicate that the use of distiller’s grain in animal diets has had a small impact on environmental footprints except that reactive N loss has increased 10%. Compared to 1970, the carbon footprint of beef produced has decreased 6% with no change in the energy footprint, a 3% reduction in the reactive N footprint, and a 6% reduction in the real cost of production. The water footprint, excluding precipitation, has increased 42% due to greater use of irrigated corn production.

Future Plans

Now that the modeling approach has been shown to appropriately represent beef production systems, further simulation analyses are planned to evaluate beef production systems on a regional and national scale.

Authors

C. Alan Rotz, Agricultural Engineer, Pasture Systems and Watershed Management Research Unit, USDA/ARS al.rotz@ars.usda.gov

B.J. Isenberg, Research Assistant, The Pennsylvania State University

K.R. Stackhouse-Lawson, Director of Sustainability Research, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association

E.J. Pollak, Director, Roman L. Hruska U.S. Meat Animal Research Center, USDA / ARS

Additional Information

C. Alan Rotz, al.rotz@ars.usda.gov

Acknowledgements

Funded in part by The Beef Checkoff and the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

From Waste to Energy: Life Cycle Assessment of Anaerobic Digestion Systems

![]() Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Waste to Worth home | More proceedings….

Abstract

In recent years, processing agricultural by-products to produce energy has become increasingly attractive due to several reasons: centralized availability of low cost by-products, avoiding the fuel vs. food debate, reduction of some associated environmental impacts, and added value that has the potential to generate additional income for producers. Anaerobic digestion systems are one waste-to-energy technology that has been proven to achieve these objectives. However, investigation on the impacts of anaerobic digestion has focused on defined segments, leaving little known about the impacts that take place across the lifecycle. Current systems within the U.S. are dairy centric with dairy manure as the most widely used substrate and electricity production as the almost sole source for biogas end use. Recently, there is more interest in exploring alternative feedstocks, co-digestion pathways, digestate processing, and biogas end uses. Different operational and design practices raise additional questions about the wide reaching impacts of these decisions in terms of economics, environment, and operational aspects, which cannot be answered with the current state of knowledge.

Why Study the Life Cycle of Anaerobic Digestion?

Waste management is a critical component for the economic and environmental sustainability of the agricultural sector. Common disposal methods include land application, which consumes large amounts of land resources, fossil energy, and produces significant atmospheric GHG emissions. Proof of this is that agriculture accounts for approximately 50% of the methane (CH4) and 60% of the nitrous oxide (N2O) global anthropogenic emissions, being livestock manure one of the major sources of these emissions (Smith et al., 2007). In the last decades, the development of anaerobic digestion (AD) systems has contributed to achieve both climate change mitigation and energy independence by utilizing agricultural wastes, such as livestock manure, to produce biogas. In addition, it has been claimed that these systems contribute to nutrient management strategies by adding flexibility to the final use and disposal of the remaining digestate. Despite these advantages, the implementation of AD systems has been slow, due to the high investment and maintenance costs. In addition, little is still known about the lifecycle impacts and fate and form of nutrients of specific AD systems, which would be useful to validate their advantages and identify strategic and feasible areas for improvement.

The main goal of this study is to quantify the lifecycle GHG emissions, ammonia emissions, net energy, and fate and form of nutrients of alternative dairy manure management systems including land-spread, solid-liquid separation, and anaerobic digestion. As cow manure is gaining an important role within the biofuel research in the pursuit for new and less controversial feedstocks, such as corn grain, the results of this study will provide useful information to researchers, dairy operators, and policy makers.

What Did We Do?

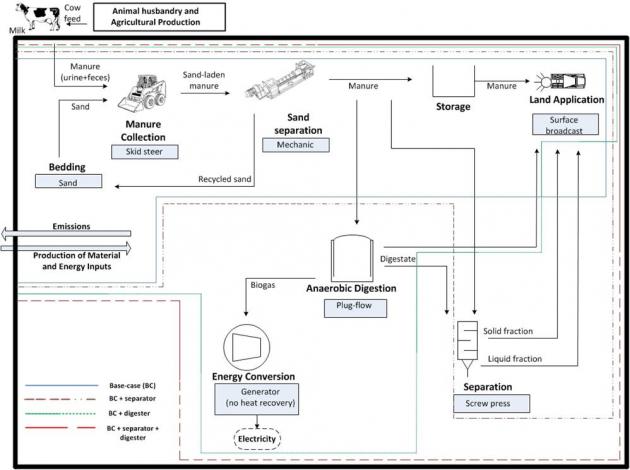

Lifecycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) methods were used to conduct this research, which is focused in Wisconsin. The state has nearly 1.3 million dairy cows that produce approximately 4.7 million dry tons of manure annually and is the leading state for implemented agricultural based AD systems. Manure from a 1,000 milking cow farm (and related maintenance heifers and dry cows) was taken as the base-case scenario. Four main processes were analyzed using the software GaBi 5 (PE, 2012) for the base case: manure production and collection, bedding sand-separation, storage, and land application. Three different manure treatment pathways were compared to the base-case scenario: including a solid-liquid mechanical separator, including a plug-flow anaerobic digester, and including both the separator and the digester. The functional unit was defined as one kilogram of excreted manure since the function of the system is to dispose the waste generated by the herd. A cradle-to-farm-gate approach was defined, but since manure is considered waste, animal husbandry and cultivation processes were not included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Embedded and cumulative energy and GHG emissions associated with the production of material and energy inputs (i.e. sand bedding, diesel, electricity, etc.) were included in the system boundaries; however, the production of capital goods (i.e. machinery and buildings) were excluded.

Figure 1. System boundaries of the base case scenario (land-spread manure) and the three manure treatment pathways: 1) solid-liquid separation, 2) anaerobic digestion, 3) anaerobic digestion and solid-liquid separation. |

Global warming potential (GWP) was characterized for a 100-year time horizon and measured in kg of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2-eq). Characterization factors used for gases other than CO2 were 298 kg CO2-eq for N2O, 25 kg CO2-eq for abiotic CH4 based on the CML 2001 method, and 24 kg CO2-eq for biotic CH4. CO2 emissions from biomass are considered to be different from fossil fuel CO2 emissions in this study; the former recycles existing carbon in the system, while the latter introduces new carbon into the atmosphere. In this context, it will be assumed that CO2 emissions from biomass sources were already captured by the plant and will not be characterized towards GWP[1]. This logic was applied when characterizing biogenic methane as one CO2 was already captured by the plant, therefore, reducing the characterization factor from 25 kg CO2-eq to 24 kg CO2-eq. Even though ammonia (NH3) does not contribute directly to global warming potential, it is considered to be an indirect contributor to this impact category (IPCC, 2006).

Data was collected from different sources to develop lifecycle inventory (LCI) as specific to Wisconsin as possible, in order to maximize the reliability, completeness, and representativeness of the model. The following points summarize some of the data sources and assumptions used to construct the LCI:

- Related research (Reinemann et al., 2010): This model provided data about animal husbandry and crop production for dairy diet in Wisconsin.

- Manure management survey: The survey, sent to dairy farms in Wisconsin, has the objective of providing information related to manure management practices and their associated energy consumption.

- In house experiments: laboratory experiments, conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, provided characterization data about manure flows before and after anaerobic digestion and solid-liquid separation and manure density in relation to total solids (Ozkaynak and Larson, 2012).

- Material and energy databases: National Renewable Energy Laboratory U.S. LCI dataset (NREL, 2008), PE International Professional database (PE, 2012), and EcoInvent (EcoInvent Center, 2007), which are built into GaBi 5. The electricity matrix used in this LCA represents the mix of fuels that are part of the electric grid of Wisconsin.

- Representative literature review.

Biotic emissions from manure have been cited to be very site specific (IPCC, 2006) and even though the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides regional emission factors, they are only for CH4 and N2O. Specific GHG emission factors were developed for Wisconsin based on the Integrated Farm System Model (IFSM) (Rotz et al., 2011), and by using key parameters that affect emissions (e.g. temperature, volatile solids, manure management practices) for each stage of the manure management lifecycle.

What Have We Learned?

Emissions are produced from consumed energy and from manure during each stage of the manure management lifecycle. In the base-case scenario, manure storage is the major contributor to GHG emissions. In this scenario, a crust tends to form on top of stored manure due to the higher total solids content when compared to digested manure and the liquid fraction of the separated manure. The formation of this crust affects overall GHG emissions (e.g. crust formation will increase N2O emissions but reduce CH4 emissions). The installation of a digester reduces CH4 emissions during storage due to the destruction of volatile solids that takes place during the digestion process. However, some of the organic nitrogen changes form to ammoniacal nitrogen, increasing ammonia and N2O emissions posterior to storage and land application. Energy consumption increases with both anaerobic digester and separation, but net energy is higher with anaerobic digestion due to the production of on-farm electricity. The nutrient balance is mostly affected by the solid-liquid separation process rather than the anaerobic digestion process.

Future Plans

A comprehensive and accurate evaluation of the lifecycle environmental impacts of AD systems requires assessing the multiple pathways that are possible for the production of biogas, which are defined based on local resources, technology, and final uses of the resulting products. A second goal of this research is to quantify the net GHG and ammonia emissions, net energy gains, and fate of nutrients of multiple and potential biogas pathways that consider different: i) biomass feedstocks (e.g miscanthus and corn stover), ii) management practices and technology choices, and iii) uses of the produced biogas (e.g. compressed biogas for transportation and upgraded biogas for pipeline injection) and digestate (e.g. bedding). This comprehensive analysis is important to identify the most desirable pathways based on established priorities and to propose improvements to the currently available pathways.

Authors

Aguirre-Villegas Horacio Andres. Ph.D. candidate. Department of Biological Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison. aguirreville@wisc.edu

Larson Rebecca. Ph.D. Assistant Professor. Department of Biological Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Additional Information

-

- Ozkaynak, A. and R.A. Larson. 2012. Nutrient Fate and Pathogen Assessment of Solid Liquid Separators Following Digestion. 2012 ASABE International Meeting, Dallas, Texas, August 2012

References

De Klein C., R. S.A. Novoa, S. Ogle, K. A. Smith, P. Rochette, T. C. Wirth, B. G. McConkey, A. Mosier, and K. Rypdal. 2006. Chapter 11: N2O emissions from managed soils, and CO2 emissions from lime and urea application. In Volume 4: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use. IPCC 2006, 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, Eggleston H.S., Buendia L., Miwa K., Ngara T. and Tanabe K. (eds). Published: IGES, Japan.

Ecoinvent Centre.2007. Ecoinvent Eata. v2.0. Ecoinvent Reports No.1-25. Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories. Dübendorf.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). 2008. U.S. Life-Cycle Inventory (LCI) Database.

Ozkaynak, A. and R.A. Larson. 2012. Nutrient Fate and Pathogen Assessment of Solid Liquid Separators Following Digestion. 2012 ASABE International Meeting, Dallas, Texas, August 2012

PE International. 2012. Software-systems and databases for lifecycle engineering.

Reinemann D. J., T.H. Passos-Fonseca, H.A. Aguirre-Villegas, S. Kraatz, F. Milani, L.E. Armentano, V. Cabrera, M. Watteau, and J. Norman. 2011. Energy intensity and environmental impact of integrated dairy and bio-energy systems in Wisconsin, The Greencheese Model.

Rotz, C. A., M. S. Corson, D. S. Chianese, F. Montes, S.D. Hafner, R. Jarvis, and C. U. Coiner. 2011. The Integrated Farm System Model (IFSM). Reference Manual Version 3.4. Accessed on Nov, 2012. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/Main/docs.htm?docid=8519

Smith, P., D. Martino, Z. Cai, D. Gwary, H. Janzen, P. Kumar, B. McCarl, S. Ogle, F. O’Mara, C. Rice, B. Scholes, O. Sirotenko. 2007: Agriculture. In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Wisconsin Institute for Sustainable Agriculture (WISA-Hatch)

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2013. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Denver, CO. April 1-5, 2013. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

What is the difference between the “higher heating value” (HHV) and “lower heating value” (LHV) of a biomass fuel, and why is the difference important?

We need these two ways of expressing the heating value of fuels because the combustion of some hydrogen-rich fuels releases water that is subsequently evaporated in the combustion chamber. In other words, the process of evaporating water “soaks up” some of the heat released by fuel combustion. That heat, known as the “latent heat of vaporization,” is temporarily lost and therefore does not contribute to the work done by the combustion process. As a result, the formation and vaporization of water in the combustion chamber reduce the amount of thermal energy available to do work, whether it be driving a piston, spinning a turbine, or superheating steam.

If the water vapor released by fuel combustion simply passes out of the chamber into the environment via the exhaust stream, the latent heat of vaporization is irreversibly and irretrievably lost. That is the case, for example, with most internal-combustion engines, such as diesel and gasoline engines. On the other hand, some advanced boilers have a secondary condensation process, downstream of the combustion step, which condenses the water vapor in the exhaust stream and recovers most of the latent heat being carried with it. The recovered heat can then be used productively.

So, in summary:

1. The numerical difference between the LHV and HHV of a fuel is roughly equivalent to the amount of latent heat of vaporization that can be practically recovered in a secondary condenser per unit of fuel burned.

2. When internal-combustion engines or boilers with no secondary condenser are designed, the appropriate fuel value to use in the design process is the LHV, which assumes that the water vapor generated when the fuel is burned goes out in the exhaust stream.

3. When advanced combustion units having secondary or tertiary condensers are designed, the appropriate fuel value to use in the design process is the HHV.

4. The numerical value of HHV is always greater than or equal to the LHV.

Thermal Manure-to-Energy Systems for Farms: Technical and Environmental Feasibility

Results of performance evaluations, including technical and environmental feasibility are presented, along with results from field trials where ash and biochars were compared side-by-side in row crop and vegetable production with commercial fertilizer and untreated poultry litter.This presentation was originally broadcast on September 18, 2015. More… Continue reading “Thermal Manure-to-Energy Systems for Farms: Technical and Environmental Feasibility”