Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

The National Air Quality Site Assessment Tool (NAQSAT) was developed as a first-of-its-kind tool to help producers and their advisors assess the impact of management on air emissions from livestock and poultry operations and identify areas for potential improvement related to those air emissions.

What did we do?

In 2007, several land-grant universities, with leadership from Michigan State University, began developing NAQSAT under a USDA-NRCS Conservation Innovation Grant (CIG). The initial tool included beef, dairy, swine, and poultry operations. A subsequent CIG project, with leadership from Colorado State University, made several enhancements to the tool, including adding horses to the species list. In 2015, USDA-NRCS officially adopted NAQSAT as an approved tool for evaluating air quality resource concerns at livestock and poultry operations. USDA-NRCS also contracted with Florida A&M University in 2015 to provide several regional training workshops on NAQSAT to NRCS employees. Six training workshops have been completed to date (Raleigh, NC; Modesto, CA; Elizabethtown, PA; Lincoln, NE; Richmond, VA; and Yakima, WA) with assistance from multiple NAQSAT development partners. Additionally, USDA-NRCS revised its comprehensive nutrient management plan (CNMP) policy in October 2015 to make the evaluation of air quality resource concerns mandatory as part of CNMP development.

What have we learned?

NAQSAT has proven to be a useful tool for bench-marking the air emissions impacts of current management on confinement-based livestock and poultry operations. In the training sessions, students have been able to complete NAQSAT runs on-site with the producer or producer representative via tablet or smartphone technologies. Further classroom discussion has helped to better understand the questions and answers and how the NAQSAT results can feed into the USDA-NRCS conservation planning process. Several needed enhancements and upgrades to the tool have been identified in order to more closely align the output of the tool to USDA-NRCS conservation planning needs. NAQSAT has also proven to be useful for evaluating the air quality resource concern status of an operation in relation to the CNMP development process.

Future Plans

It is anticipated that the identified needed enhancements and upgrades will be completed as funding for further NAQSAT development becomes available. Additionally, as use of NAQSAT by USDA-NRCS and our conservation planning and CNMP development partners expands, additional training and experience-building opportunities will be needed. The NAQSAT development team has great geographic coverage to assist in these additional opportunities.

Corresponding author, title, and affiliation

Greg Zwicke, Air Quality Engineer – Air Quality and Atmospheric Change Team, USDA-NRCS

Corresponding author email

Other authors

Greg Johnson, Air Quality and Atmospheric Change Team Leader, USDA-NRCS; Jeff Porter, Animal Nutrient and Manure Management Team Leader, USDA-NRCS; Sandy Means, Agricultural Engineer – Animal Nutrient and Manure Management Team, USDA-NRCS

Additional information

naqsat.tamu.edu

https://lpelc.org/naqsat-for-swine-and-poultry

https://lpelc.org/naqsat-for-beef-and-dairy/

Acknowledgements

C.E. Meadows Endowment, Michigan State University

Colorado Livestock Association

Colorado State University

Florida A&M University

Iowa Turkey Federation

Iowa Pork Producers

Iowa Pork Industry Center

Iowa State University

Iowa State University Experiment Station

Kansas State University

Michigan Milk Producers Association

Michigan Pork Producers Association

Michigan State University

Michigan State University Extension

National Pork Board

Nebraska Environmental Trust

Oregon State University

Penn State University

Purdue University

Texas A&M University

University of California, Davis

University of Georgia

University of Georgia Department of Poultry Science

University of Idaho

University of Maryland

University of Maryland Department of Animal and Avian Sciences

University of Minnesota

University of Missouri

University of Nebraska

USDA-ARS

Virginia Tech University

Washington State University

Western United Dairymen

Whatcom County (WA) Conservation District

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2017. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Cary, NC. April 18-21, 2017. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

Proceedings Home

Proceedings Home

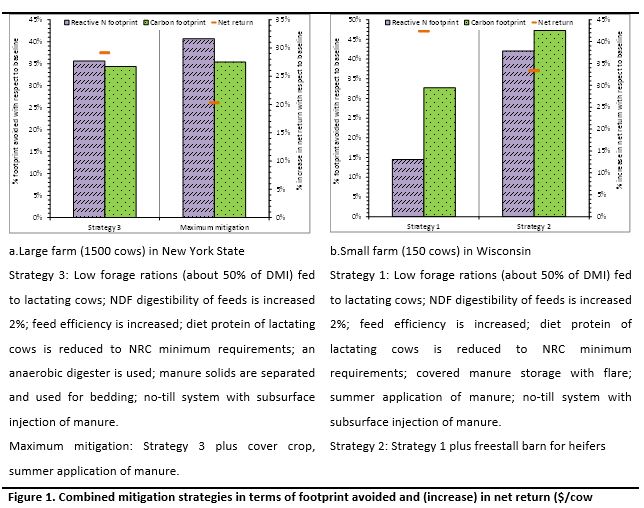

ost basic then drilling down to peer-reviewed publications, data from life-cycle assessment studies and models related to the topics. The Virtual Farm focuses on decision makers and stakeholders including consumers, producers, policymakers, scientists and students who are interested in milk production on modern dairy farms. The top entry level of the site navigates through agricultural topics of interest to the general public. Producers can navigate to a middle level to learn about practices and how they might help them continue to produce milk for consumers responsibly in a changing climate while maintaining profitability. Featured beneficial (best) management practices (BMPs) reflect options related to dairy sustainability, climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, and milk production. Researchers can navigate directly to deeper levels to publications, tools, models, and scientific data. The website is designed to encourage users to dig deeper and discover more detailed information as their interest develops related to sustainable dairies and the environment.

ost basic then drilling down to peer-reviewed publications, data from life-cycle assessment studies and models related to the topics. The Virtual Farm focuses on decision makers and stakeholders including consumers, producers, policymakers, scientists and students who are interested in milk production on modern dairy farms. The top entry level of the site navigates through agricultural topics of interest to the general public. Producers can navigate to a middle level to learn about practices and how they might help them continue to produce milk for consumers responsibly in a changing climate while maintaining profitability. Featured beneficial (best) management practices (BMPs) reflect options related to dairy sustainability, climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, and milk production. Researchers can navigate directly to deeper levels to publications, tools, models, and scientific data. The website is designed to encourage users to dig deeper and discover more detailed information as their interest develops related to sustainable dairies and the environment.