Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

Resiliency to weather extremes is a topic that Northern Plains farmers and ranchers are already familiar with, but now climate change is adding new uncertainties that make it difficult to know the best practices for the future. Scenario planning is a method of needs assessment that will allow Extension and beef system stakeholders to come together using the latest climate science to discover robust management options, highlight key uncertainties, prioritize Extension programming needs, and provide an open forum for discussion for this sometimes controversial topic.

Overall objectives:

1. Determine a suite of key future scenarios based on climate science that are plausible, divergent, relevant, and challenging to the beef industry.

2. Determine robust management options that address the key scenario drivers.

3. Develop a plan for Extension programming to address determined educational needs.

What did we do?

A team of researchers, Extension specialists, and educators was formed with members from University of Nebraska and South Dakota State University. They gathered the current research information on historical climate trends, projections in future climate for the region, and anticipated impacts to the beef industry. These were summarized in a series of white papers.

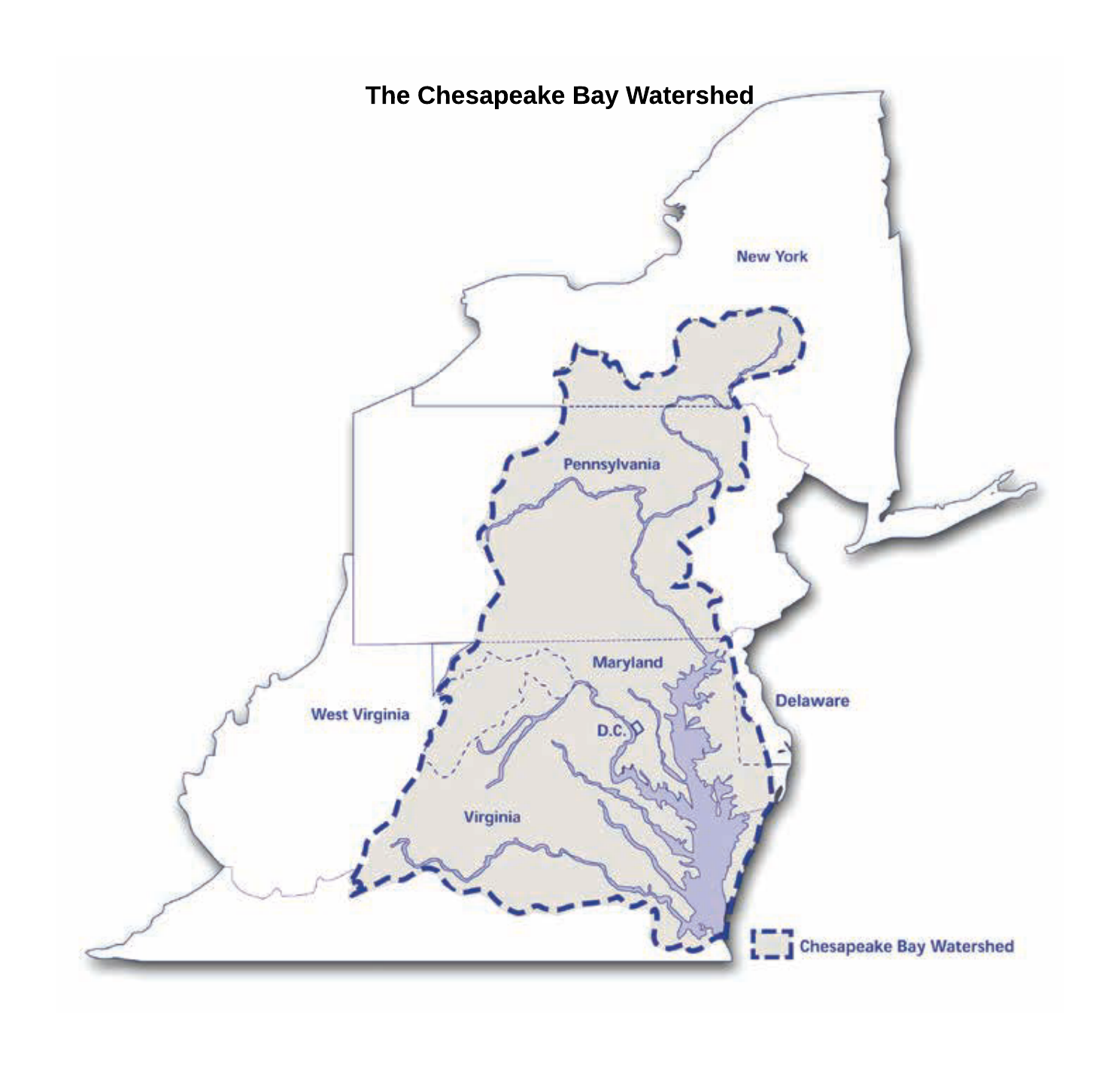

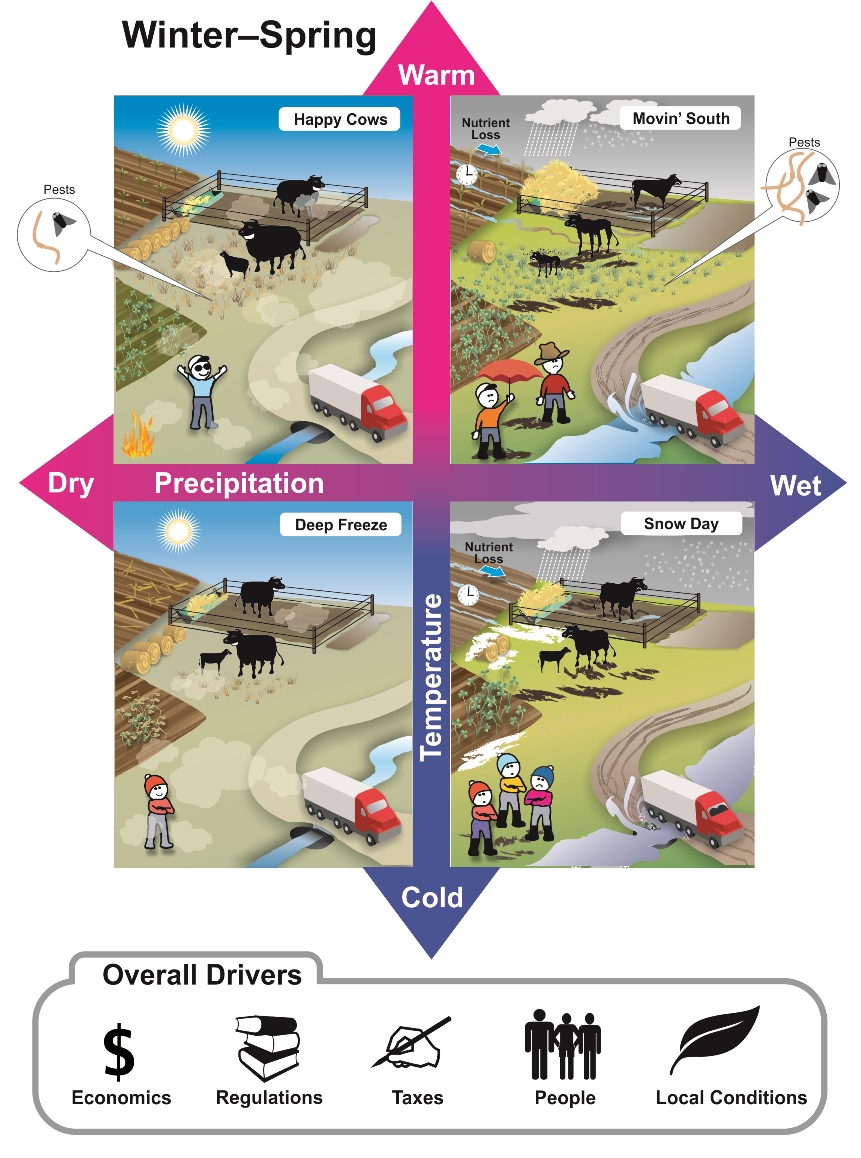

Three locations were selected to host two half day focus groups, representing the major production regions. A diverse group representing the beef industry of each region including feedlot managers, cow calf ranchers, diversified producers, veterinarians, bankers, NRCS personnel, and other allied industries. The first focus group started with a discussion of the participants past experiences with weather impacts. The team then provided short presentations starting with historic climate trends and projection, anticipated impacts, and uncertainties. The participants then combined critical climate drivers as axis in a 2×2 grids, each generating a set of four scenarios. They then listed impacts for each combination. The impacts boundaries were feed production through transporting finished cattle off-farm.

Project personnel then combined the results of all three locations to prioritize the top scenarios, which were turned into a series of graphics and narratives. The participants were then brought together for a second focus group to brainstorm management and technology options that producers were already implementing or might consider implementing. These were then sorted based on their effectiveness across multiple climate scenarios, or robustness. The options where also sorted by the readiness of the known information: Extension materials already available, research data available but few Extension materials, and research needed.

What have we learned?

The key climate drivers were consistent across all focus groups: temperature and precipitation, ranging from below average to above average. In order to best capture the impacts, the participants separated winter/spring and summer/fall.

This method of using focus groups as our initial interaction with producers on climate change was well received. Most all farmers love to talk about the weather, so discussing historical trends and their experiences with it as well as being upfront with the uncertainties in future projections, while emphasizing the need for proactive planning seemed to resonate.

With so many competing interests for producers’ time, as well as a new programming area, it was critical to have trusted local educators to invite participants. Getting participants to the second round of focus groups was also more difficult, so future efforts should considering hosting a single, full day focus group, or allowing the participants to set the date for the second focus group, providing more motivation to attend.

Future Plans

The scenarios and related management options will be used to develop and enhance Extension programming and resources as well as inform new research efforts. The goal is to provide a suite of robust management options and tools to help producers make better decisions for their operation.

Corresponding author, title, and affiliation

Crystal Powers, Extension Engineer, University of Nebraska – Lincoln

Corresponding author email

Other authors

Rick Stowell, Associate Professor at University of Nebraska – Lincoln

Additional information

Crystal Powers

402-472-0888

155 Chase Hall, East Campus

Lincoln, NE 68583

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the project team:

University of Nebraska – Lincoln: Troy Walz, Daren Redfearn, Tyler Williams, Al Dutcher, Larry Howard, Steve Hu, Matthew Luebbe, Galen Erickson, Tonya Haigh

South Dakota State University: Erin Cortus, Joseph Darrington,

This project was supported by the USDA Northern Plains Regional Climate Hub and Agricultural and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant No. 2011-67003-30206 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2017. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Cary, NC. April 18-21, 2017. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

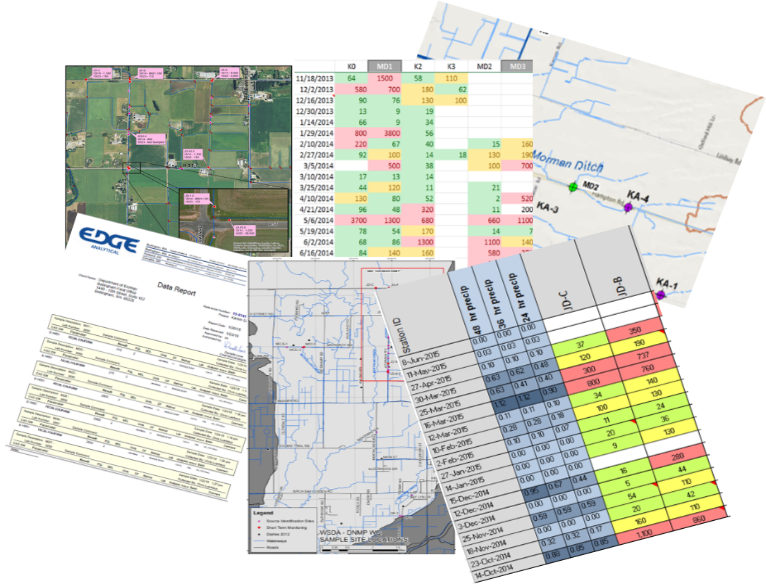

ased engagement from our dairy producers, with many checking the results map regularly for updates. The map is symbolized with graduated stop light symbology, with poor water quality shown in red and good in green. If they see a red dot or “hot spot” in their neighborhood they may stop us on the street, send an email, or call with ideas or observations of what they believe may have influenced water quality. It has opened the door to conversations and partnerships in identifying and correcting possible influences from their farm.

ased engagement from our dairy producers, with many checking the results map regularly for updates. The map is symbolized with graduated stop light symbology, with poor water quality shown in red and good in green. If they see a red dot or “hot spot” in their neighborhood they may stop us on the street, send an email, or call with ideas or observations of what they believe may have influenced water quality. It has opened the door to conversations and partnerships in identifying and correcting possible influences from their farm.