Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

This analysis of methane emissions used a “bottom-up” approach based on animal inventories, feed dry matter intake, and emission factors to estimate county-level enteric (cattle) and manure (cattle, swine, and poultry) methane emissions for the contiguous United States.

What did we do?

Methane emissions from enteric and manure sources were estimated on a county-level and placed on a map for the lower 48 states of the US. Enteric emissions were estimated as the product of animal population, feed dry matter intake (DMI), and emissions per unit of DMI. Manure emission estimates were calculated using published US EPA protocols and factors. National Agricultural Statistic Services (NASS) data was utilized to provide animal populations. Cattle values were estimated for every county in the 48 contiguous states of the United States. Swine and poultry estimates were conducted on a county basis for states with the highest populations of each species and on a state-level for less populated states. Estimates were placed on county-level maps to help visual identification of methane emission ‘hot spots’. Estimates from this project were compared with those published by the EPA, and to the European Environmental Agency’s Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR).

What have we learned?

Overall, the bottom-up approach used in this analysis yielded total livestock methane emissions (8,888 Gg/yr) that are comparable to current USEPA estimates (9,117 Gg/yr) and to estimates from the global gridded EDGAR inventory (8,657 Gg/yr), used previously in a number of top-down studies. However, the spatial distribution of emissions developed in this analysis differed significantly from that of EDGAR.

Methane emissions from manure sources vary widely and research on this subject is needed. US EPA maximum methane generation potential estimation values are based on research published from 1976 to 1984, and may not accurately reflect modern rations and management standards. While some current research provides methane emission data, a literature review was unable to provide emission generation estimators that could replace EPA values across species, animal categories within species, and variations in manure handling practices.

Future Plans

This work provides tabular data as well as a visual distribution map of methane emission estimates from enteric (cattle) and manure (cattle, swine, poultry) sources. Future improvement of products from this project is possible with improved manure methane emission data and refinements of factors used within the calculations of the project.

Corresponding author, title, and affiliation

Robert Meinen, Senior Extension Associate, Penn State University Department of Animal Science

Corresponding author email

Other authors

Alexander Hristov (Principal Investigator), Professor of Dairy Nutrition, Penn State University Department of Animal Science Michael Harper, Graduate Assistant, Penn State University Department of Animal Science Richard Day, Associate Professor of Soil

Additional information

None.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by ExxonMobil Research and Engineering.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2017. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Cary, NC. April 18-21, 2017. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

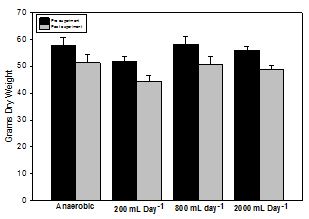

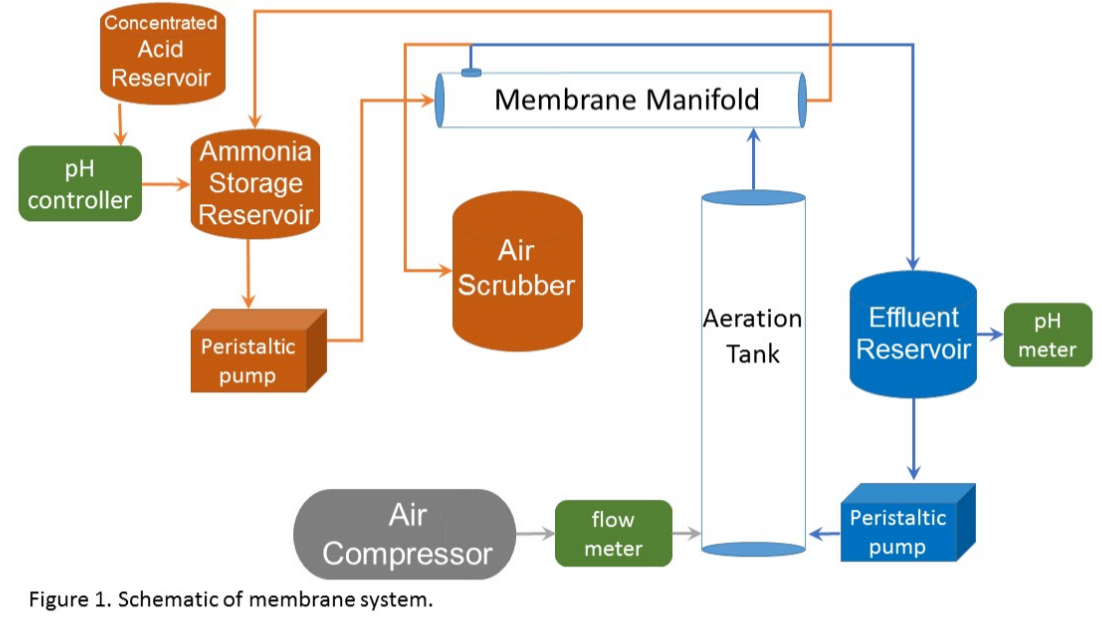

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.

Four digesters were constructed out of 55 gallon sprayer tanks. The digestate was 132 L in volume with a dynamic headspace of 76 L. At the bottom of each tank a manifold was constructed from ½” PVC pipe in an “H” configuration and with a volume of approximately 230 mL. The bottom of the manifold had holes drilled in it to allow exchange with the sludge. Tanks were fed 400 g of used top dressing chicken litter (wood shaving bedding) obtained from a local producer (averaging 40% moisture and 15% ash) in 2 L of water through a port in the tank [labeled “1” in figure]. Two hundred mL of air were fed to the manifold through a flow meter [2] 0, 1, 4, or 10 times daily in 15-minute periods at widely spaced intervals by means of an air pump and rotary timer [4]. A gas port [3] at the top of the tank allowed for sampling and led to a wet tip flow meter (wettipflowmeters.com) to measure gas production. Digestate samples were taken out of a side port [5] for measurement of water quality and dissolved gases and overflow was discharged from the tank by means of a float switch wired in line with a ½” PVC electrically actuated ball valve.