Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

Why Tackle Mortality Management? It’s Ripe for Revolution.

The poultry industry has enjoyed a long run of technological and scientific advancements that have led to improvements in quality and efficiency. To ensure its hard-won prosperity continues into the future, the industry has rightly shifted its focus to sustainability. For example, much money and effort has been expended on developing better management methods and alternative uses/destinations for poultry litter.

In contrast, little effort or money has been expended to improve routine mortality management – arguably one of the most critical aspects of every poultry operation. In many poultry producing areas of the country, mortality management methods have not changed in decades – not since the industry was forced to shift from the longstanding practice of pit burial. Often that shift was to composting (with mixed results at best). For several reasons – improved biosecurity being the most important/immediate – it’s time that the industry shift again.

The shift, however, doesn’t require reinventing the wheel, i.e., mortality management can be revolutionized without developing anything revolutionary. In fact, the mortality management practice of the future owes its existence in part to a technology that was patented exactly 20 years ago by Tyson Foods – large freezer containers designed for storing routine/daily mortality on each individual farm until the containers are later emptied and the material is hauled off the farm for disposal.

Despite having been around for two decades, the practice of using on-farm freezer units has received almost no attention. Little has been done to promote the practice or to study or improve on the original concept, which is a shame given the increasing focus on two of its biggest advantages – biosecurity and nutrient management.

Dusting off this old BMP for a closer look has been the focus of our work – and with promising results. The benefits of hitting the reset button on this practice couldn’t be more clear:

- Greatly improved biosecurity for the individual grower when compared to traditional composting;

- Improved biosecurity for the entire industry as more individual farms switch from composting to freezing, reducing the likelihood of wider outbreaks;

- Reduced operational costs for the individual poultry farm as compared to more labor-intensive practices, such as composting;

- Greatly reduced environmental impact as compared to other BMPs that require land application as a second step, including composting, bio-digestion and incineration; and

- Improved quality of life for the grower, the grower’s family and the grower’s neighbors when compared to other BMPs, such as composting and incineration.

What Did We Do?

We basically took a fresh look at all aspects of this “old” BMP, and shared our findings with various audiences.

That work included:

- Direct testing with our own equipment on our own poultry farm regarding

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors,

- Freezer unit capacity,

- Power consumption, and

- Operational/maintenance aspects;

- Field trials on two pilot project farms over two years regarding

- Freezer unit capacity

- Quality of life issues for growers and neighbors,

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors,

- Operational and collection/hauling aspects;

- Performing literature reviews and interviews regarding

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors

- Pathogen/disease transmission,

- Biosecurity measures

- Nutrient management comparisons

- Quality of life issues for growers and neighbors

- Ensuring the results of the above topics/tests were communicated to

- Growers

- Integrators

- Legislators

- Environmental groups

- Funding agencies (state and federal)

- Veterinary agencies (state and federal)

What Have We Learned?

The breadth of the work at times limited the depth of any one topic’s exploration, but here is an overview of our findings:

- Direct testing with our own equipment on our own poultry farm regarding

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors

- Farm visitation by scavenger animals, including buzzards/vultures, raccoons, foxes and feral cats, that previously dined in the composting shed daily slowly decreased and then stopped entirely about three weeks after the farm converted to freezer units.

- The fly population was dramatically reduced after the farm converted from composting to freezer units. [Reduction was estimated at 80%-90%.]

- Freezer unit capacity

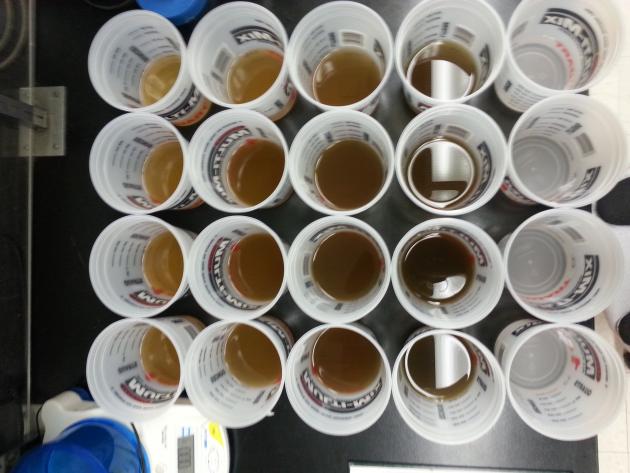

- The test units were carefully filled on a daily basis to replicate the size and amount of deadstock generated over the course of a full farm’s grow-out cycle.

- The capacity tests were repeated over several flocks to ensure we had accurate numbers for creating a capacity calculator/matrix, which has since been adopted by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service to determine the correct number of units per farm based on flock size and finish bird weight (or number of grow-out days) in connection with the agency’s cost-share program.

- Power consumption

- Power consumption was recorded daily over several flocks and under several conditions, e.g., during all four seasons and under cover versus outside and unprotected from the elements.

- Energy costs were higher for uncovered units and obviously varied depending on the season, but the average cost to power one unit is only 90 cents a day. The total cost of power for the average farm (all four units) is only $92 per flock. (See additional information for supporting documentation and charts.)

- Operational/maintenance aspects;

- It was determined that the benefits of installing the units under cover (e.g., inside a small shed or retrofitted bin composter) with a winch system to assist with emptying the units greatly outweighed the additional infrastructure costs.

- This greatly reduced wear and tear on the freezer component of the system during emptying, eliminated clogging of the removable filter component, as well as provided enhanced access to the unit for periodic cleaning/maintenance by a refrigeration professional.

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors

- Field trials on two pilot project farms over two years regarding

- Freezer unit capacity

- After tracking two years of full farm collection/hauling data, we were able to increase the per unit capacity number in the calculator/matrix from 1,500 lbs. to 1,800 lbs., thereby reducing the number of units required per farm to satisfy that farm’s capacity needs.

- Quality of life issues for growers and neighbors

- Both farms reported improved quality of life, largely thanks to the elimination or reduction of animals, insects and smells associated with composting.

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors

- Both farms reported elimination or reduction of the scavenging animals and disease-carrying insects commonly associated with composting.

- Operational and collection/hauling aspects

- With the benefit of two years of actual use in the field, we entirely re-designed the sheds used for housing the freezer units.

- The biggest improvements were created by turning the units so they faced each other rather than all lined up side-by-side facing outward. (See additional information for supporting documentation and diagrams.) This change then meant that the grower went inside the shed (and out of the elements) to load the units. This change also provided direct access to the fork pockets, allowing for quicker emptying and replacement with a forklift.

- Freezer unit capacity

- Performing literature reviews and interviews regarding

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors

- More research confirming the connection between farm visitation by scavenger animals and the use of composting was recently published by the USDA National Wildlife Research Center:

- “Certain wildlife species may become habituated to anthropogenically modified habitats, especially those associated with abundant food resources. Such behavior, at least in the context of multiple farms, could facilitate the movement of IAV from farm to farm if a mammal were to become infected at one farm and then travel to a second location. … As such, the potential intrusion of select peridomestic mammals into poultry facilities should be accounted for in biosecurity plans.”

- Root, J. J. et al. When fur and feather occur together: interclass transmission of avian influenza A virus from mammals to birds through common resources. Sci. Rep. 5, 14354; doi:10.1038/ srep14354 (2015) at page 6 (internal citations omitted; emphasis added).

- More research confirming the connection between farm visitation by scavenger animals and the use of composting was recently published by the USDA National Wildlife Research Center:

- Pathogen/disease transmission,

- Animals and insects have long been known to be carriers of dozens of pathogens harmful to poultry – and to people. Recently, however, the USDA National Wildlife Research Center demonstrated conclusively that mammals are not only carriers – they also can transmit avian influenza virus to birds.

- The study’s conclusion is particularly troubling given the number and variety of mammals and other animals that routinely visit composting sheds as demonstrated by our research using a game camera. These same animals also routinely visit nearby waterways and other poultry farms increasing the likelihood of cross-contamination, as explained in this the video titled Farm Freezer Biosecurity Benefits.

- “When wildlife and poultry interact and both can carry and spread a potentially damaging agricultural pathogen, it’s cause for concern,” said research wildlife biologist Dr. Jeff Root, one of several researchers from the National Wildlife Research Center, part of the USDA-APHIS Wildlife Services program, studying the role wild mammals may play in the spread of avian influenza viruses.

- Animals and insects have long been known to be carriers of dozens of pathogens harmful to poultry – and to people. Recently, however, the USDA National Wildlife Research Center demonstrated conclusively that mammals are not only carriers – they also can transmit avian influenza virus to birds.

- Biosecurity measures

- Every day the grower collects routine mortality and stores it inside large freezer units. After the broiler flock is caught and processed, but before the next flock is started – i.e. when no live birds are present, a customized truck and forklift empty the freezer units and hauls away the deadstock. During this 10- to 20- day window between flocks biosecurity is relaxed and dozens of visitors (feed trucks, litter brokers, mortality collection) are on site in preparation for the next flock.

- “Access will change after a production cycle,” according to a biosecurity best practices document (enclosed) from Iowa State University. “Empty buildings are temporarily considered outside of the [protected area and even] the Line of Separation is temporarily removed because there are no birds in the barn.”

- Every day the grower collects routine mortality and stores it inside large freezer units. After the broiler flock is caught and processed, but before the next flock is started – i.e. when no live birds are present, a customized truck and forklift empty the freezer units and hauls away the deadstock. During this 10- to 20- day window between flocks biosecurity is relaxed and dozens of visitors (feed trucks, litter brokers, mortality collection) are on site in preparation for the next flock.

- Nutrient management comparisons

- Research provided by retired extension agent Bud Malone (enclosed) provided us with the opportunity to calculate nitrogen and phosphorous numbers for on-farm mortality, and therefore, the amount of those nutrients that can be diverted from land application through the use of freezer units instead of composting.

- The research (contained in an enclosed presentation) also provided a comparison of the cost-effectiveness of various nutrient management BMPs – and a finding that freezing and recycling is about 90% more efficient than the average of all other ag BMPs in reducing phosphorous.

- Quality of life issues for growers and neighbors

- Local and county governments in several states have been compiling a lot of research on the various approaches for ensuring farmers and their residential neighbors can coexist peacefully.

- Many of the complaints have focused on the unwanted scavenger animals, including buzzards/vultures, raccoons, foxes and feral cats, as well as the smells associated with composting.

- The concept of utilizing sealed freezer collection units to eliminate the smells and animals associated with composting is being considered by some government agencies as an alternative to instituting deeper and deeper setbacks from property lines, which make farming operations more difficult and costly.

- Farm visitation by animals and other disease vectors

Future Plans

We see more work on three fronts:

- First, we’ll continue to do monitoring and testing locally so that we may add another year or two of data to the time frames utilized initially.

- Second, we are actively working to develop new more profitable uses for the deadstock (alternatives to rendering) that could one day further reduce the cost of mortality management for the grower.

- Lastly, as two of the biggest advantages of this practice – biosecurity and nutrient management – garner more attention nationwide, our hope would be to see more thorough university-level research into each of the otherwise disparate topics that we were forced to cobble together to develop a broad, initial understanding of this BMP.

Corresponding author (name, title, affiliation)

Victor Clark, Co-Founder & Vice President, Legal and Government Affairs, Farm Freezers LLC and Greener Solutions LLC

Corresponding author email address

Other Authors

Terry Baker, Co-Founder & President, Farm Freezers LLC and Greener Solutions LLC

Additional Information

https://rendermagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Render_Oct16.pdf

Farm Freezer Biosecurity Benefits

One Night in a Composting Shed

—

Avian flu conditions still evolving (editorial)

USDA NRCS Conservation fact sheet Poultry Freezers

How Does It Work? (on-farm freezing)

Influenza infections in wild raccoons (CDC)

Collection Shed Unit specifications

Collection Unit specifications

Freezing vs Composting for Biosecurity (Render magazine)

Manure and spent litter management: HPAI biosecurity (Iowa State University)

Acknowledgements

Bud Malone, retired University of Delaware Extension poultry specialist and owner of Malone Poultry Consulting

Bill Brown, University of Delaware Extension poultry specialist, poultry grower and Delmarva Poultry Industry board member

Delaware Department of Agriculture

Delaware Nutrient Management Commission

Delaware Office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service

Maryland Office of the Natural Resources Conservation Service

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2017. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Cary, NC. April 18-21, 2017. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.