Purpose

A new approach for recovering nutrients and value-added products from waste is to search for a synergistic effect by combining two or more wastes. This work improved the recovery of phosphorus and proteins/amino acids abundant in swine manure by adding a second waste or product rich in sugars, such as molasses, fruit waste, or lactose waste. The second waste rich in sugars acted as a natural acid generator that replaced purchased acids and lowered the overall recovery cost.

What Did We Do?

A new approach was developed to separate and recover concentrated phosphorus and proteins from animal waste (Vanotti and Szogi, 2019). It was improved by adding a second waste or product containing sugars, such as molasses and fruit waste (Vanotti et al., 2020). They could be used as a natural acid precursor that replaces purchased acids and lowers the overall cost of phosphorus and protein recovery. In this study, the two model wastes were swine manure solids (source of extractable phosphorus and proteins) and peach waste (source of acid precursors).

What Have We Learned?

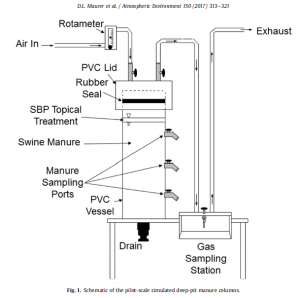

On a dry-weight basis, the swine manure solids contained high amounts of proteins (15.2%) and phosphorus (2.9%) available for extraction. It was shown that waste peaches, an abundant waste in the Southeastern USA with no cost except transportation, contain about 8% total sugars and can be used as an acid precursor to effectively extract phosphorus and proteins from swine manure (waste peaches were peaches that were too soft, had bad spots, or did otherwise not meet the grade at the Processing Plant for sale as fresh fruit). The waste peaches (Brix 7.7 deg) were added to the manure, and the combo received rapid fermentation (24-h) after adding an inoculum (Vanotti et al., 2020). Adding fruit waste to the manure and rapid fermentation produced abundant natural acids – lactic acid, citric acid, and malic acid – that effectively solubilized the phosphorus in the manure (Fig. 1). Further, the peach fermentation did not adversely affect the protein recovery from the manure. A pH of about five or less is a valuable target to optimize the phosphorus and protein recovery from manure. The target was successfully met using a variety of natural acid precursors (fructose, molasses, peaches, lactose). The phosphorus was precipitated with calcium or magnesium compounds, obtaining concentrated phosphate products with > 90% plant-available phosphorus. The proteins/amino acids in the manure were quantitatively recovered. Other fruits, vegetables, and food waste products also contain significant amounts of sugar, so this is not limited to only wasted peaches. It is contemplated that other sugar-containing agricultural by-products could be used in this process for the same purpose with minor adjustments for amounts depending on the sugar concentration and initial pH of the fruit or vegetable.

Future Plans

Research will be presented showing consistent phosphorus extraction results obtained with swine manure and sugar beet molasses as the acid precursor, and with dairy manure and lactose waste as the acid precursor. USDA-ARS seeks a commercial partner to bring this technology to market. For more information on commercialization, contact: Mrs. Tanaga Boozer, Technology Transfer Coordinator, USDA-ARS, OTT Southeast Area, tanaga.boozer@usda.gov

Authors

Presenting & corresponding author

Matias Vanotti, USDA-ARS, Matias.vanotti@usda.gov

Additional authors

Vanotti, M.B, Szogi, A.A., and Brigman, P.W. USDA-ARS, Florence, SC

Moral, R. Miguel Hernandez University, Orihuela, Spain

Additional Information

Vanotti, M.B., Szogi, A.A. 2019. Extraction of amino acids and phosphorus from biological materials. US Patent 10,150,711. US Patent & Trademark Office.

Vanotti, M.B., Szogi, A.A., Moral, R. 2020. Extraction of amino acids and phosphorus from biological materials using sugars (acid precursors). US Patent 10,710,937. US Patent & Trademark Office.

Vanotti, M., Szogi, A., Moral, R., & Brigman, W. 2023 (November). Recovery of Value-Added Products from Swine Manure and Waste Peaches. In National Conference on Next-Generation Sustainable Technologies for Small-Scale Producers (NGST 2022) (pp. 38-42). Atlantis Press.

Acknowledgements

This research was part of USDA-ARS National Program 212, ARS Project 6082-12630-001-00D. Support by Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Japan, through ARS Project 58-6082-7-006-F, is also acknowledged. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7-11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.