Purpose

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is a major concern to the U.S. swine industry due to the severe economic loss it can cause. Its symptoms include severe flu-like symptoms, respiratory distress, fever, and premature abortions in pregnant sows. The virus is spread during close contact between pigs or exposure to contaminated urine, semen, feces, and nasal and mammary secretions (1). Control measures have proven exceedingly costly with PRRSV which causes an estimated $1 billion in lost production in the U.S. pork industry per year (3), an 80% increase from a decade earlier (2)(4). With very few, truly effective methods available to control PRRSV after the start of an outbreak, developing methods to mitigate the dispersion of the virus has become a major priority.

Common biosecurity measures for swine operations (e.g., controlled access, personal hygiene, animal management, pest control, and production area cleaning and disinfection) have proved insufficient to stop PRRSV transmission. Producers are, therefore, seeking to understand the potential risks posed by more novel transport methods. Observations of new PRRSV cases emerging during manure handling activities have raised questions about aerosolized manure as a potential transmission vector. This study was conducted to test this possibility in the following stages:

-

- Verify the presence of viable virus sample within pit manure, lagoon samples, or dust coming from barns with active PRRSv outbreaks.

- Develop a reliable method for collecting and preserving viable airborne viral samples.

- Assess the aerosol transmission “footprint” of PRRSV originating from positive swine farms to improve understanding of potential farm-to-farm disease transmission risks.

What Did We Do?

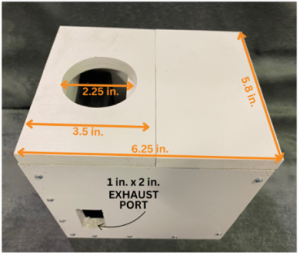

Novel air sampling devices were constructed by the project team (Figure 1) to be deployed inside and outside swine production units to accumulate samples of particulates and aerosols. The devices accommodate a commercially available Air Prep filter cartridge (innovaprep.com) to capture particulates pulled across the filter by a fan housed within the sampling unit.

Our project team worked closely with the lead veterinarian at a large swine integrator in Nebraska to access farms within 5 to 7 d of pigs being confirmed PRRSV-positive. Sampling events 1 and 2 focused on evaluating PRRSV presence on indoor surfaces, fresh and stored manure, flies, and maggots. Sampling events 3 through 5 focused on evaluating PRRSV presence in air downwind of PRRSV-positive swine production areas or downwind of land application of manure from PRRSV-positive animals.

Sampling Event 1. A swine breeding operation was identified where animals were currently testing positive for and showing clinical signs of PRRSV infection. At this site, two production areas were selected at random for sampling. Surface swabs were collected from floors, fan louvers, and pen dividers. Fresh fecal samples were collected from sows in the same production areas, and an air sampler was placed on the floor in each room and allowed to operate for two hours before retrieving the filters. For surface samples, sterile swabs were swept over each surface type and then placed into phosphate buffered saline (PBS) elution buffer. Fresh fecal samples were collected using a sterile spatula and placed into clean sample containers. Upon retrieving filters from air samplers, a sterilized knife was used to separate the filter from the plastic casing in which it was mounted, and sterile forceps were used to transfer the filter into a PBS elution tube. All samples were transported on ice to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) Schmidt Lab and then submitted to the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Sampling Event 2. A swine finisher unit was identified where animals were currently testing positive for and showing clinical signs of PRRSV infection. At this site, two production areas were selected at random for sampling inside the building. Surface swabs were collected from floors, fan louvers, feeders, and pen dividers. An air sampler was placed on the floor in each room and allowed to operate for four hours before retrieving the filters. Additional air samplers were mounted outside the building. For one production area, three samplers were mounted at a height aligning with the center of a minimum ventilation fan and spaced at 5, 12, and 19 feet from the rim of the fan hood. For a second production area, two samplers were mounted at a height aligning with the center of a minimum ventilation fan and spaced at 5 and 13 feet from the rim of the fan hood. These samplers were allowed to run for three hours before filters were retrieved. For surface samples, sterile swabs were swept over each surface type and then placed into PBS elution buffer. Manure samples from two deep pit storage sections of the building were collected using a plastic pole and dipper cup and placed into clean plastic bottles. Maggots observed in one pump out port were collected by hand and placed into PBS elution buffer. Upon retrieving filters from air samplers, a sterilized knife was used to separate the filter from the plastic casing in which it was mounted, and sterile forceps were used to transfer the filter into a PBS elution tube. Flies present around the production buildings were also collected at this site. For one sample, approximately six flies were captured and placed directly into PBS elution buffer. For a second sample, approximately six flies were captured, placed into 70% EtOH for 10 s, and then transferred from the ethanol to PBS elution buffer. All samples were transported on ice to the UNL Schmidt Lab and then submitted to the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for analysis by PCR.

Sampling Event 3. A naturally-ventilated PRRSV-positive swine farm was identified. Air samplers mounted on t-posts were deployed in an array at a height above the ground of roughly 6 ft at varying distances (10 yards to 1 mile) from the buildings after using smoke candles to confirm wind direction and dispersion. Sampling was conducted for approximately 2.5 hours on a day with 40-55°F temperature,10-20 mph winds, and full cloud cover (Figure 2).

Sampling Event 4. At a mechanically-ventilated PRRSV-positive swine farm, sampling was conducted using the same process as for Event 3 for approximately 21.25 hours starting on a day with 85-105°F temperature, 4-10 mph winds, and full sun exposure, then continuing overnight.

Sampling Event 5. Using the previously described process, sampling was conducted for approximately 2.5 hours on a day with 70-95°F temperature, 2-10 mph winds, and partly cloudy conditions downwind of a field where lagoon effluent from PRRSV-positive pigs was being applied via center pivot.

All samples were submitted to the Iowa State Veterinary Diagnostic Lab for RT-qPCR analysis to identify PRRS viral genomic material.

What Have We Learned?

Results of PCR analyses for sampling event 1 (Table 1) revealed that, in barns where swine oral fluid samples were positive for PRRSv, all surface samples collected were also positive or suspected positive for PRRSv. The same was true for all of the surface and air samples collected inside the barn and for the air samples located up to 19 ft minimum from the building ventilation fans during sampling event 2 (Table 2). Maggots taken from the manure pit during sampling event 2, along with sterilized and unsterilized flies, tested positive for PRRSV, as well. Conversely, all manure samples obtained during sampling event 2 tested negative using the methodologies employed. This outcome does not dismiss manure as a possible transmission source; rather, it underscores the need for ongoing research to develop a reliable detection method for PRRS within such a complex matrix.

The team has not yet recovered air samples testing positive for PRRSV from any of the exterior arrays in sampling events 3-5 (Table 3). This could be due to ambient air conditions during the tests which may have caused rapid destruction of the virus or dilution of the virus below detectable concentrations. The rolling terrain surrounding facilities where arrays of samplers were posted downwind of buildings or the land application site may have created turbulent air movement that diluted samples such that concentrations of PRRSV genomic material capture on filters were too low to produce a positive result by PCR.

Table 1. Cycle Threshold (Ct) values for sampling event 1

| Sample Description | Ct (Result) |

| Pen Floor, Room 17 | 37.5 (Suspect) |

| Fan Louver, Room 17 | 30.1 (Positive) |

| Feeder, Room 17 | 31.6 (Positive) |

| Air Filter, Room 17 | 31.2 (Positive) |

| Pen Floor, Room 18 | 31.5 (Positive) |

| Fan Louver, Room 18 | 31.4 (Positive) |

| Feeder, Room 18 | 37.6 (Suspect) |

| Air Filter, Room 18 | 30.5 (Positive) |

| Fecal Sample 1 | ³40 (Negative) |

| Fecal Sample 2 | ³40 (Negative) |

Cycle threshold (Ct) indicates the number of PCR cycles required for the sample fluorescence to reach a predefined threshold for identification (<38 = positive, ~38-40 = suspect, ≥40 = negative). Lower Ct values correspond to higher viral RNA concentration.

Table 2. Cycle Threshold (Ct) values for sampling event 2

| Sample Description | Ct (Result) |

| Exhaust Air, Room 5, 5 ft from fan | 33.1 (Positive) |

| Exhaust Air, Room 5, 12 ft. from fan | 34.1 (Positive) |

| Exhaust Air, Room 5, 19 ft. from fan | 38.1 (Suspect) |

| Indoor Air, Room 5, Rep 1 | 30.9 (Positive) |

| Indoor Air Room 5, Rep 2 | 33.3 (Positive) |

| Exhaust Air, Room 6, 5 ft from fan | 32.6 (Positive) |

| Exhaust Air, Room 6, 13 ft. from fan | 32.4 (Positive) |

| Flies | 37.0 (Suspect) |

| Flies Sterilized in Ethanol | 36.3 (Positive) |

| Maggots | 39.9 (Suspect) |

| Floor, Room 5, Rep 1 | 32.4 (Positive) |

| Floor, Room 5, Rep 2 | 32.3 (Positive) |

| Louvers, Room 5, Rep 1 | 33.1 (Positive) |

| Louvers, Room 5, Rep 2 | 32.1 (Positive) |

| Pens, Room 5, Rep 1 | 37.9 (Positive) |

| Pens, Room 5, Rep 2 | 35.8 (Positive) |

| Feeder, Room 5, Rep 1 | 35.8 (Positive) |

| Feeder, Room 5, Rep 2 | 37.5 (Suspect) |

| Pens, Room 4, Rep 1 | 35.6 (Positive) |

| Pens, Room 4, Rep 2 | 35.3 (Positive) |

| Floor, Room 4, Rep 1 | 31.4 (Positive) |

| Floor, Room 4, Rep 2 | 32.9 (Positive) |

| Louvers, Room 4, Rep 1 | 33.0 (Positive) |

| Louvers, Room 4, Rep 2 | 32.1 (Positive) |

Cycle threshold (Ct) indicates the number of PCR cycles required for the sample fluorescence to reach a predefined threshold for identification (<38 = positive, ~38-40 = suspect, ≥40 = negative). Lower Ct values correspond to higher viral RNA concentration.

Table 3. Cycle Threshold (Ct) values for sampling events 3 through 5

| Sampling Event | Sample Description | Ct (Result) |

| Event 3 | Air Filters (n=2) | ³40 (Negative) |

| Event 4 | Air Filters (n=4) | ³40 (Negative) |

| Fans (n=4) | ³40 (Negative) | |

| Oral Fluids, Room 15 | 34.0 (Positive) | |

| Oral Fluids, Room 16 | 36.1 (Positive) | |

| Oral Fluids, Room 17 | 38.0 (Suspect) | |

| Oral Fluids, Room 18 | 34.7 (Positive | |

| Event 5 | Air Filters (n=4) | ³40 (Negative) |

Cycle threshold (Ct) indicates the number of PCR cycles required for the sample fluorescence to reach a predefined threshold for identification (<38 = positive, ~38-40 = suspect, ≥40 = negative). Lower Ct values correspond to higher viral RNA concentration.

Future Plans

It is essential to identify which ambient weather conditions, if any, are favorable for air dispersion of infective PRRSv and which conditions will significantly limit dispersion. As research continues, the suspected ideal conditions for sampling downwind of mechanically ventilated PRRSv-positive barns or irrigation systems applying lagoon effluent from PRRSv-positive pigs will be 0 to 50°F with low to moderate wind speed and full cloud cover. At least 24 hours of continuous sampling is also expected to produce greater opportunity for positive air samples.

The continued inability to isolate the virus from manure samples is curious, given the universally positive samples we identified from the positive barns. However, the PRRSV is believed to require as few as 10 viral particles to be transmitted. Given the potentially very low concentration of viral material in manure, and the significant PCR inhibitors present in complex organic samples, the team continues to explore new sample preparation and testing methods for this matrix.

Lastly, further investigation into the potential roles of flies and maggots is warranted, particularly with the discovery of sufficient PRRSV genomic material in the gut of surface sterilized flies to yield a positive PRRSV result via RT-qPCR.

Authors

Presenting author

Logan Hafer, Undergraduate Research Assistant, Department of Biological Systems Engineering, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Corresponding author

Dr. Amy Millmier Schmidt, Professor, Department of Biological Systems Engineering and Department of Animal Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, aschmidt@unl.edu

Additional author(s)

Dr. Benny Mote, Associate Professor, Department of Animal Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Dr. Hiep Vu, Associate Professor, Department of Animal Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Additional Information

-

- Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (PRRSV). Iowa State University – College of Veterinary Medicine; 2024 [accessed 2024 November 22]. https://vetmed.iastate.edu/vdpam/FSVD/swine/index-diseases/porcine-reproductive.

- Butler, J. E., Lager, K. M., Golde, W., Faaberg, K. S., Sinkora, M., Loving, C., & Zhang, Y. I. 2014. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS): an immune dysregulatory pandemic. Immunologic research, 59, 81-108. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12026-014-8549-5.

- Dee, S., T. Clement, and E. Nelson. 2023. Transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in domestic pigs via oral ingestion of feed material. J of the Am Vet Med Assoc, 262(1). https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.23.08.0447

- Osemeke, O.H., T. Donovan, K. Dion, D.J. Holtkamp and D.C.L. Linhares. 2021. Characterization of changes in productivity parameters as breeding herds transitioned through the 2021 PRRSV Breeding Herd Classification System. J Swine Health Prod. 2022;30(3):145-148. https://doi.org/10.54846/jshap/1269

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the Nebraska Pork Producers Association under award #22-063 and an Undergraduate Student Research Program award from the UNL Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Agricultural Research Division.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2025. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Boise, ID. April 7–11, 2025. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.