Home | Trends | Manure Management | Nutrients | Water Quality | Clean Water Act | Stewardship (You are here) | Conservation | Conservation Practices

Managing manure as a beneficial resource involves:

- being aware of potential water quality issues

- knowing and following the rules that apply to animal agriculture

- practicing sound nutrient management

- taking advantage of appropriate options for realizing the benefits of manure

Building on the previous sections in this module, this section focuses on tools and resources for managing manure-related risks and highlights strategies for good stewardship. It highlights assessing risk, siting, planning for emergencies, getting along with neighbors, and keeping records.

“It’s all about sustainability. The more we know, the more we can plan, and the better job we can do. There’s always new information, new knowledge and new technology.”

Marie Audet, Blue Spruce Farm; U.S. Innovation Center for Dairy 2015 Sustainability Award Winner

Recommended Resources on Planning for Stewardship

- Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook Chapter 2: Planning Considerations (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service)

- Livestock and Poultry Environmental Stewardship (LPES) curriculum Lesson 1: Principles of Environmental Stewardship

- NPDES Permit Writers’ Manual for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (U.S. EPA)

- Beneficial Uses of Manure (U.S. EPA)

- Best Management Practices To Minimize Agricultural Phosphorus Impacts on Water Quality (USDA Agricultural Research Service)

This module focuses on water quality, but stewardship also includes attention to air quality, odor and nuisance concerns, and aesthetics (appearance).

Location! Location! Location!

Selecting an appropriate site for manure storage, feed storage, open lots, barns, stockpiles, and land application is a critical first step when looking at building new structures or expanding existing ones. Assessments of existing farm sites should identify risk areas to be avoided or where improvements are needed to protect water resources.

Below are potential pollution sources and some of the factors that should be considered when assessing the risks to environmentally sensitive features when siting and designing operations. These lists are not comprehensive but provide some common areas for consideration.

Potential Pollution Sources

- Manure storage

- Animal lots and barns

- Feed storage

- Dead animal burial, composting, or pickup site

- Open lots or corrals

- Land application

- Field stockpiles of manure

- Pesticide, chemical, fuel storage

Factors Influencing Pollution Potential

- Distance

- Soil type

- Slope

- Presence of tiles and other drains, pipes, ditches, culverts or other conveyances

- Cross-connections in water supply and/or waste systems

- Vegetative cover

Environmental Features of Special Concern

- Wells and wellhead protection areas (groundwater)

- Rivers, streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands and other water

- Sinkholes, karst topography

- Neighbors, public spaces

- Threatened or endangered species or habitats

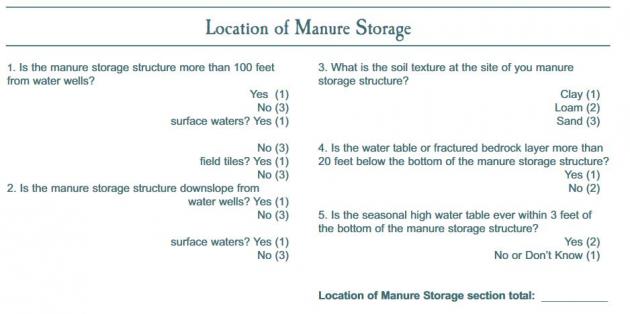

Assessing risk is a very site-specific exercise. In one situation, 100 feet between a potential pollutant and a stream may be perfectly acceptable, such as when the buffer has extensive vegetation and little slope. In other situations, even a 100-foot buffer might be inadequate, such as when the buffer is subject to channelized flow due to erosion. There are a variety of tools to help producers assess the risk of particular siting decisions, such as Farm*A*Syst. Figure 1 provides an example of the type of questions asked in such tools to guide producers the best siting choice.

Figure 1. Sample Farm*A*Syst style risk assessment worksheet. This one is from Utah State University extension.

Photo 1. (Above) An example of poor siting that was later corrected. The area roughly outlined in orange was originally an animal pen at this feedlot. The run-on of stormwater from the crop field was not diverted around the pen nor was the subsequent runoff from the pen contained. A combination of water quality concerns and poor cattle performance resulted in the farm owner evaluating different options. They chose to relocate the pen to the other side of the feedlot (not shown; right side of photo). The new pen has no run-on and the manure and runoff are completely contained.

In many cases, specific regulatory requirements prescribe how to assess and address site-specific risk. As a general rule, regulatory standards should be thought of as a starting point for good nutrient management while recognizing that site-specific conditions may require additional controls to adequately protect sensitive features.

Recommended Resources for Site Selection or Assessing Risks Related to Animal Feeding and Manure Management

Do a search for “Farm A Syst” + your state name to find worksheets created to assess water quality risks around farms utilizing state-specific recommendations and considerations. If you cannot locate Farm*A*Syst materials this way, contact your local or state extension service to find out if that or a similar resource exists in your state. These worksheets cover a broad range of topics, including animal lots and manure but also chemicals, fuel, septic systems and more.

- NRCS Agricultural Waste Management Field Handbook Chapter 8: Siting Agricultural Waste Management System

- Water Quality Index tool (NRCS) is focused on field risk to surface water quality (also see the help file)

Emergency Response Planning

Regular monitoring and timely maintenance of manure storage and handling equipment is one of the best ways to prevent accidental spills and releases. Most releases or discharges causing water quality problems are preventable with appropriate management. However, occasionally accidents or emergencies due to unforeseen conditions or events do occur. Having a plan for when things go wrong is essential. A crisis is no time to wonder who to call, look up phone numbers, or figure out the location of needed supplies. Planning for events like catastrophic animal mortalities, an unresponsive person in or around a manure pit, or a manure spill saves time, possibly lives, and can lessen the environmental impact.

An emergency response plan for a manure spill should include several steps:

- Stop the leak. Eliminate further spillage. Does everyone know how to shut off the pumps and close valves (or where these items are located)? Notify emergency responders as needed for human safety, traffic control, or other safety matters. Always prioritize matters of human safety first!

- Contain the spill. Do you have equipment to build a temporary earthen berm? If not, who does? Are hay bales, stakes, sheets of plastic and plywood or similar items readily available for blocking culverts, tile drains, or ditches?

- Assess the spill. How much spilled? How far did the spill flow or spread?

- Notify the appropriate agency. There is no national database on the number of manure spills that occur each year. Most spills are reported to state authorities.

- Clean up the spill. The equipment needed will depend on whether the spill is solid or liquid/slurry manure. Procedures will also vary depending on if or how much manure reached waterways. See the “Responding to a Manure Spill” section below for case studies.

- Make repairs and restore the site. Fix any faulty equipment, hoses, valves, pumps, etc. Ensure roadways are clean, and spilled manure is either land applied appropriately or transferred to a different storage structure. Remove temporary berms and blockages. Reseed the site if necessary.

- Train employees and family. Practice the plan. The plan should be reviewed, updated as necessary, and everyone on the farm trained on an annual basis.

Responding To a Manure Spill: Case Studies, Templates and Other Resources

Always check with your state extension service to see if they have templates and resources for spill response and other emergency situations. Templates may be pre-populated with important phone numbers or requirements for notification, and some Extension systems even maintain a list of contractors to assist with cleanup.

- Animal Waste Management Field Handbook Chapter 13 “Operation, Maintenance, and Safety” covers preventative management and safety considerations. (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service)

- [Video] How to respond to a manure spill (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

- LPES Lesson 50 “Emergency Action Plans” is a comprehensive resource (48 pages). It includes six case studies (pages 10-13) and recommendations for cleanup procedures and templates (starting on page 33).

- Manure spill case studies (Ontario Livestock Manure Pollution Prevention Working Group)

- [Video] Emergency response planning (University of Minnesota)

The video below presents two case studies of excellent manure spill response efforts. It is excerpted from Kevin Erb’s (University of Wisconsin) presentation in the webinar “Manure Spills and Emergency Planning“. That link will also take you to videos and links for the steps for a spill response, solid manure considerations, and steps/technologies to prevent manure spills.

Photos 2-4 below include critiques of a manure spill response from 2005. These are intended as a learning exercise and should not discourage efforts to clean up manure spills. A less-than-perfect spill response is much better than no response at all. All three photos are courtesy of Kevin Erb, University of Wisconsin.

Photo 2. (Above) Using bales to stop future erosion from the site is a good temporary measure for low grade slopes and unchannelized flow. However, these bales should be staked into the ground to be effective. If sod is disturbed, the area should be reseeded and covered with straw or mulch to suppress weeds.

Photo 3. (Above) Spilled manure was removed from the ditch; however, sod was removed along with the manure. This increases the potential for erosion. It also removes the plants that could use the manure nutrients. The sod removal was done above buried utility lines. This is discouraged, and probably illegal in most locations.

Photo 4. (Above) The areas above and below the culvert were cleaned up post-spill. However, the culvert was not flushed out. Not only did this create a “stinky mess” but could potentially flow downslope with the next rain.

Record Keeping

One common problem encountered when a complaint is made about a farm or an emergency situation is examined, is missing or incomplete records. The most important thing to remember about records is “If you don’t document it, you did not do it!” If there are no records of manure spreader calibration or manure nutrient analysis, the entire nutrient plan can be undermined. While a farmer knows to inspect and maintain equipment, he or she needs to be able to prove that inspection or maintenance in the event of a spill, an inspection or a complaint.

A common way to organize records is by how often they need to be accessed. Some records are permanent, such as farm maps and design schematics of the manure storage. These are not accessed every day and can be filed securely. Records that need to be filled out daily, such as rainfall records, should be in a handy location like a clipboard or a smartphone. One Nebraska farmer bought mailboxes and installed them in several locations where inspections and observations needed to be made often including the manure storage and weather station. Electronic technologies, apps, GPS, and computer software can be used and new features are being introduced regularly in public and privately-developed programs.

| Records need to be backed up regularly and protected in case of situations like fire, flood, or electrical surges. Have a plan for backing up important records. |

In the following video Christine Blanton with North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources discusses why records are important and how they can be useful in making management decisions. While the emphasis is on records for permitted operations, the information is relevant to all animal feeding operations.

Recommended Resources for Record Keeping

Do an Internet search for “animal feeding operation record keeping templates” + your state name to see if there are checklists and forms already developed for your area. These can always be modified.

- Sample Record Keeping Forms for Animal Feeding Operation (Heartland Regional Water Quality Coordination Project)

- Critical Records of Ag Production (C.R.A.P.) is a record keeping app developed at Utah State University for manure transfers, application, equipment inspections and other important operations

Getting Along With Neighbors

“I provide a business card with my number to all of the neighbors and ask them to call me anytime with questions or concerns, allowing them to also give me advance notice if they have a get together or event that our crews should be aware of. I say to call anytime they have a question or concern. I stop by once per year, even to the neighbors who don’t like me.”

Wisconsin dairy farmer – on the topic of neighbor relations

Animal feeding operations can be the source of odors, flies, traffic and other nuisance issues for neighbors. Doing as much as possible to minimize nuisances, listen to neighbor concerns, and maintain positive relationships within the community is important not only for animal agriculture, but any business.

A very helpful exercise to define a farm’s stewardship ethic, and be able to communicate it to those outside the farm, is to create an environmental policy statement (EPS). An EPS is a short paragraph that describes the farm and commits to stewardship, regulatory compliance and continual improvement. The policy statement can be used on a farm website, on brochures, posted on the office wall, and should be among the first things given to new employees. It provides a framework for talking about what is important to a farm when talking with neighbors and others in the community.

Recommended Resources on Neighbor Relations

- Building Good Neighbor Relationships (Purdue University)

- Farmer-to-Farmer Advice for Avoiding Conflicts (Rutgers University)

- [Video] Managing Odors and Neighbor Relations (University of Minnesota)

- Coexisting with Neighbors (University of Georgia) Developed for poultry farmers, but relevant to all animal feeding operations

Review, Reassess, and Improve

One common characteristic shared by farms that plan for stewardship is a desire to continually improve upon current efforts. This mindset is very comparable to an environmental management system (EMS) process in which a plan is developed, implemented, monitored, and then reviewed for improvements. The new plan is implemented, and so on. Taking an honest look at mistakes and learning from them is part of continual improvement.

“We cannot stand idle. If we do, the industry will pass us by, and we’ll be out of business. This philosophy of continuous improvement has led the family toward updates that contribute to the operation’s sustainability.”

Lee Bateman of Bateman’s Mosida Farms; Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy 2016 Sustainability Award Winner

Case Studies and Examples

See part three of this module for recommended resources on nutrient management.

- [Recorded webinar] Management of Confined Livestock Systems from a Producer’s Perspective (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service). This recording features several farmers that made significant changes to their operation. They share experiences with using technical or financial assistance programs, learning from other producers, and challenges.

- [Waste to Worth 2013 conference proceedings] Case Study Closure of an Earthen Lagoon (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service)

- Animal Waste Management Field Handbook Chapter 15 Computer Software and Models (USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service)

- Effects of observability and complexity on farmers’ adoption of environmental practices (Journal of Environmental Planning and Management)

Several national producer associations recognize outstanding members with environmental stewardship awards including the Pork Board, Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy, U.S. Poultry & Egg, and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Previous: Regulatory Requirements | Next: The Importance of Conservation

Acknowledgments

These materials were developed by the Livestock and Poultry Environmental Learning Center (LPELC) with funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and with input from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, National Milk Producers Federation, National Pork Board, United Egg Producers, and U.S. Poultry and Egg Association.

For questions on these materials, contact Jill Heemstra, jheemstra@unl.edu. All images in this module, unless indicated otherwise, were provided by Jill.

Reviewers: Tetra Tech, Inc.; Joe Harrison, Washington State University; and Tom Hebert, Bayard Ridge Group