Proceedings Home | W2W Home

Purpose

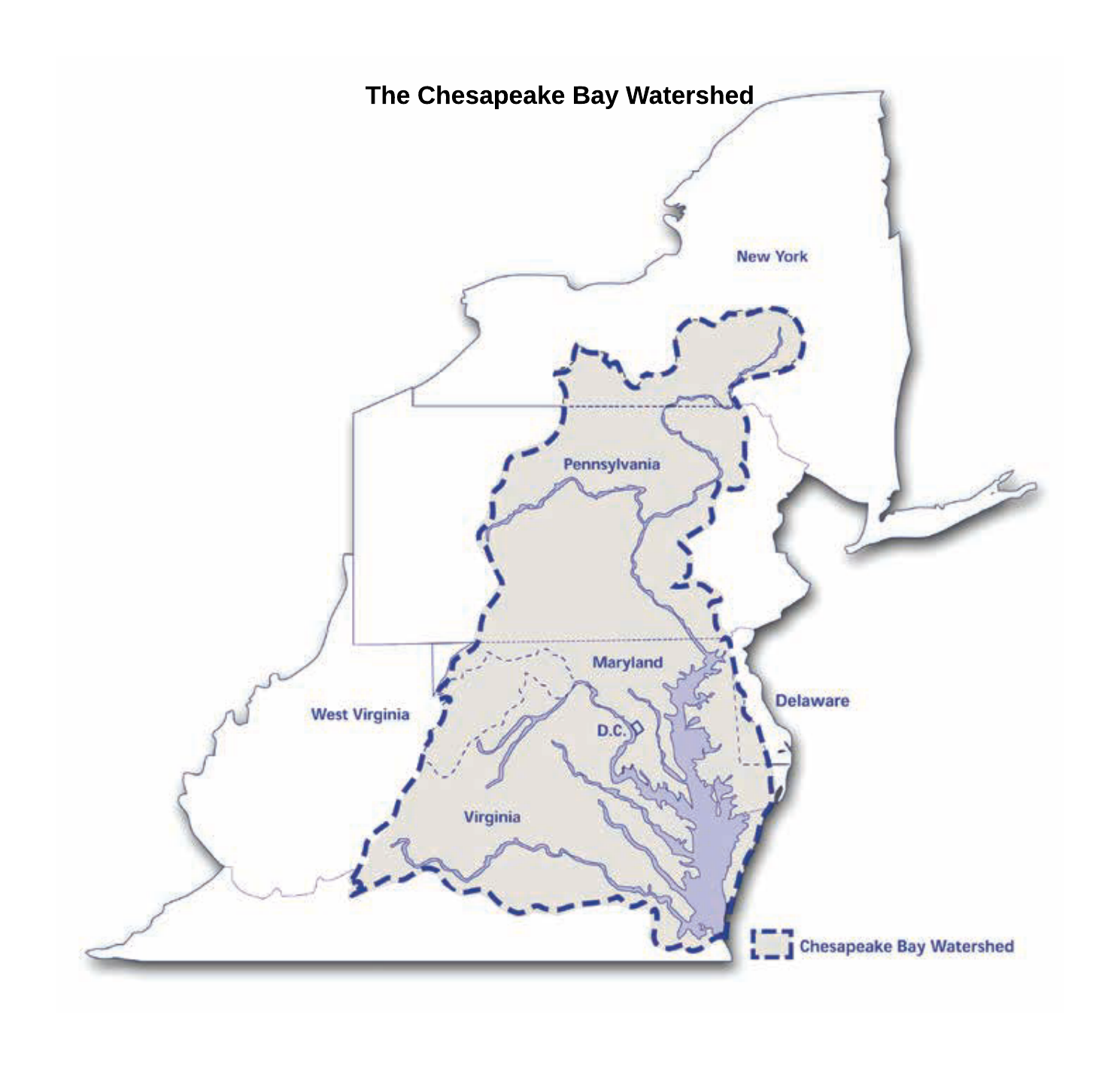

The Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) is a regional partnership that leads and directs Chesapeake Bay restoration and protection. The CBP uses a suite of modeling and planning tools to estimate nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorus) and sediment loads contributed to the Bay from its watershed, and guide restoration efforts. Non-point source (NPS) pollutant sources (e.g., agricultural and urban runoff) are largely related to diverse land uses stretching across six states and the District of Columbia. On-the-ground pollutant reductions are achieved by implementing both management and structural best management practices (BMPs) on those diverse land uses. Short and long-term reductions in NPS pollutant loads that result from BMP implementation are estimated using the CBP modeling suite of tools. The CBP recognizes (i.e., represents pollutant reduction credits for) over 150 BMPs across 66 land uses total for all sectors in its Phase 6 suite of modeling tools. The estimated pollutant reduction performance (i.e., effectiveness) of each BMP is parameterized in the CBP modeling suite. Within the CBP, BMP effectiveness is determined by groups of qualified scientific and technical experts (BMP Expert Panels) that review the relevant literature and make an independent determination regarding BMP performance which are reviewed and approved by the CBP partnership before being integrated in to the modeling tools by the CBP modeling team.

BMP Expert Panels are primarily convened under the auspices of the CBP’s Water Quality Goal Implementation Team and tasked to specific sector workgroups for oversight and management. Panels are tasked with addressing a specific BMP, or a suite of related BMPs. Panel members, in coordination with the CBP partnership, are selected based on their scientific expertise, practical experience with the BMP, and expertise in fate and transport of nutrients and sediment. Panels review the relevant literature and through a deliberative process and form recommendations on BMP pollutant production performance, and how the BMP(s) should be accounted for/incorporated into the CBP modeling tools and data reporting systems. Convening BMP Expert Panels is an ongoing focus and priority of the CBP partnership, given the integral role BMP implementation plays in achieving the pollution reduction goals required by the 2010 Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL).

What Did We Do?

Expert panels follow the process and adhere to expectations outlined in the Chesapeake Bay Program Partnership’s Protocol for the Development, Review, and Approval of Loading and Effectiveness Estimates for Nutrient and Sediment Controls in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Model (aka the “BMP Protocol”). The expert panel process functions as an independent peer review, similar to that of the National Academy of Sciences.

Each panel reviews and discusses all current published literature and available unpublished literature and data related to the BMP(s), and formulates recommendations using the guidance provided in the BMP Protocol to help weigh the applicability of each data source. Consensus panel recommendations are recorded in a final report, which is presented to relevant CBP partnership groups, including the CBP partnership’s Agriculture Workgroup for feedback and approval.

Panel recommendations are built into the modeling tools following CBP partnership approval of the panel’s report.

What Have We Learned?

The availability of published, peer-reviewed data varies greatly based on the scope of the panel. Some panels have dozens of articles to analyze while others may have a limited number of published studies to supplement gray literature, unpublished data and their best professional judgment. Even panels with a large amount of relevant literature at their disposal identify important gaps and future research needs. Given the wide range of stakeholders in the CBP partnership, regular updates and communication with interested parties as the panel formulates its recommendations is extremely important to improve understanding and acceptance of final panel recommendations.

Future Plans

The Chesapeake Bay Program evaluates BMP effectiveness estimates as new research or new conservation and production practices become available. Thus, expert panels sometimes revisit BMPs that were previously reviewed, but new and innovative BMPs are also considered. The availability of resources and new research limit the frequency of these reviews in conjunction with the priorities of the CBP partnership. Given the CBP partnership’s interest in adaptive management and continually improving its scientific estimates of BMP effectiveness, there will continue to be BMP expert panels for the foreseeable future.

Corresponding author (name, title, affiliation)

Jeremy Hanson, Project Coordinator – Expert Panel BMP Assessment, Virginia Tech

Corresponding author email address

Other Authors

Mark Dubin, Agricultural Technical Coordinator, University of Maryland Extension

Brian Benham, Professor and Extension Specialist, Virginia Tech

Each expert panel has at least several other authors and contributors, which is not practical for listing here. Each individual report identifies the panel members and other contributors for that specific panel.

Additional Information

The BMP Review Protocol is available online at http://www.chesapeakebay.net/publications/title/bmp_review_protocol

All final expert panel reports are posted on the Chesapeake Bay Program website under “publications”: http://www.chesapeakebay.net/groups/group/bmp_expert_panels

Acknowledgements

These BMP expert panels would not be possible without the generosity of expert panel members who volunteer their valuable time and perspectives. Staff support, coordination and funding for these panels is provided by the EPA Chesapeake Bay Program, specifically through Cooperative Agreements with Virginia Tech and University of Maryland, with additional contract support from Tetra Tech as needed. The work of these expert panels is strengthened through the participation, review and comments of the CBP partnership.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2017. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth: Spreading Science and Solutions. Cary, NC. April 18-21, 2017. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.

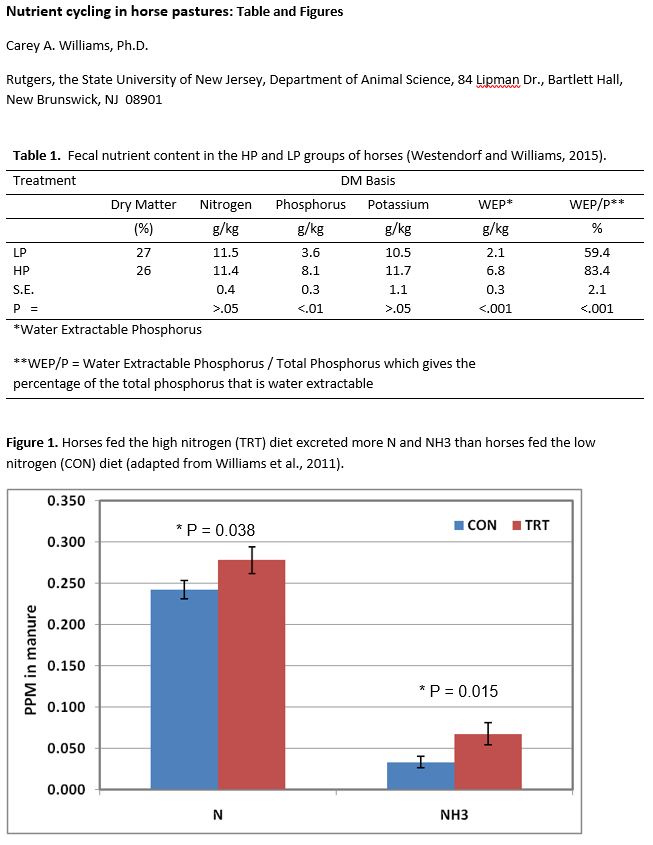

Project 1- documented conservation and farm management practices on 23 equine operations, quantitatively evaluated pasture desirable plants and canopy cover, sampled feed, hay and soil, and conducted nutrient management audits. Pasture data, collected using line point transect methodology, included calculation of percent canopy cover, basal stems and desirable forage. The 23 surveyed operations were used to develop a baseline for total nutrient balances and levels for the Pennsylvania horse industry.

Project 1- documented conservation and farm management practices on 23 equine operations, quantitatively evaluated pasture desirable plants and canopy cover, sampled feed, hay and soil, and conducted nutrient management audits. Pasture data, collected using line point transect methodology, included calculation of percent canopy cover, basal stems and desirable forage. The 23 surveyed operations were used to develop a baseline for total nutrient balances and levels for the Pennsylvania horse industry.