Over the last 15 years it has become common to build new poultry production facilities on a piece of property that will provide the necessary land area for all of the barns and support facilities, and that comply with the setbacks (i.e. surface water, nearest neighbors) required by local, state, and federal regulations. The manure management plan in such cases depended on the transport of poultry manure to remote cropland that was often not owned and managed by the poultry producer. In some states, the law held the poultry producer legally responsible for any possible environmental consequences associated with irresponsible spreading or handling. Such laws tended to limit transport distances due to the lack of liability transfer. In other states, like South Carolina, poultry manure brokers were required to have a state permit that allowed for the transfer of liability from the producer to the broker by means of a contract. The broker became liable for proper application rates, adherence to setback requirements, application at agronomic rates, and other state requirements. While transfer of liability did encourage the movement of manure from nearby fields with high soil-test phosphorous contents to remote fields that could benefit from all plant nutrients in manure it also gave rise to an increase in the number or farms that were permitted with manure brokerage as the only manure nutrient management alternative.

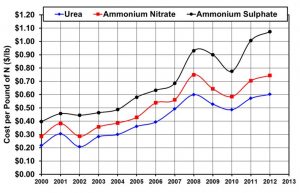

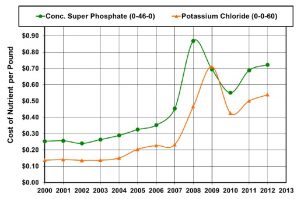

During the period from 2002 to 2008 when many new poultry farms were being built the average prices of N, P2O5, and K2O were increasing due to surges in fuel prices. Nitrogen prices increased in a linear manner from 29 to 75 cents per pound or a 2.6 fold increase in price (Table 1 and Figure 1). Prices of the other major nutrients, P2O5 and K2O, increased by over a factor of 3 for the same six year period (Figure 2). Such increases in the cost of fertilizers greatly increased demand for poultry manure, and further encouraged poultry producers to build barns that depended on brokerage as the only manure management option without any considerations of potential decreases in manure value. In recent years, fertilizer prices have decreased and brokerage of manure is not as attractive. The objective of this study was to determine the impact of fertilizer price fluctuations on the value of broiler litter, high-rise layer manure, turkey grow-out litter, and turkey brooder litter.

| Table 1. Fertilizer composition information and equation used to convert price per ton to price per pound. | |

|---|---|

| Fertilizer Description | Nutrient Content Per Ton of Fertilizer |

| Urea – 46% N by weight | 920 lb N/ton |

| Ammonium Nitrate – 34% N by weight | 680 lb N/ton |

| Ammonium Sulfate – 21% N and 24% by weight | 420 lb N/ton |

| Conc. Super-Phosphate – 46% P2O5 by weight | 920 lb P2O5 /ton |

| Potassium Chloride – 60% K2O by weight | 1200 K2O / ton |

| Equation Used to Convert Fertilizer Price to Price per Pound of Nutrient | $ / lb Nutrient = $ / Ton of Fertilizer÷ lb Nutrient / Ton |

What did we do?

Fertilizer Nutrient Content of Poultry Manure

The type of poultry raised in a building and the amount of bedding used causes a wide variation in the plant nutrient content of the manure removed from the building. The manure composition used in the study was taken from data obtained in South Carolina and is shown in Table 2. Broiler litter and turkey grow-out litter were the most similar since pine shavings were used as bedding and several flocks of birds were grown-out on the litter prior to building clean-out. Clean-out frequency varies greatly from every 1 to 1.5 years. The data shown in Table 2 corresponded to annual litter clean-out. The moisture contents (MC) of these two litters were also similar (24% for the broiler litter and 26% for the turkey grow-out litter). Turkey production begins on a brooder farm where chicks are placed, brooded, and the poults are transported to a grow-out farm. These farms are unique in that the litter was completely changed after each flock. The result is that litter from a brooder farm is much drier (14% moisture content) and contains less manure than any other type of poultry manure. The lower manure content also resulted in lower plant nutrient content. Manure from a high-rise layer barn was at the other extreme. Since no bedding was added to the manure the moisture content was much higher (47%). The high moisture content resulted in lower plant available nitrogen (PAN) content as compared to broiler litter, as well as lower phosphorus content (expressed as P2O5) and potassium (expressed as K2O).

| Table 2. Poultry manure composition (lb / ton) used in the analysis (Chastain et al, 2001). | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient | Broiler Litter(MC = 24%) | Layer Manure(MC = 47%) | Turkey Grow-out Litter (MC = 26%) | Turkey Brooder Litter (MC = 14%) |

| Ammonium-N | 10 | 12 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Nitrate-N | 3.6 | None detected | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Org-N | 43.8 | 22 | 42 | 37.2 |

| Total-N | 57.4 | 34 | 54 | 40.4 |

| PAN – inc * | 38 | 23 | 35 | 25 |

| P2O5 | 66 | 51 | 64 | 29 |

| K2O | 57 | 26 | 37 | 20 |

| * PAN – inc. = Incorporated plant available N = 0.60 x Org-N + 0.80 x Ammonium-N + Nitrate-N | ||||

Data for all three forms of nitrogen are provided in Table 2. However, not all of the nitrogen in manure is available for use by a crop. For this study, it was assumed that poultry manure was incorporated on the same day that it was applied by disking. As a result, 80% of the ammonium-N was counted as plant available. The amount of organic-N (Org-N) mineralized was assumed to be 60% based on common recommendations in South Carolina, however mineralization rates vary based on soil temperature, pH, and moisture. All the small amounts of nitrate contained in the manure was counted as available. The equation used for PAN estimates is provided with the table. Additional information concerning the estimate of plant available-N is provided by Chastain et al (2001).

The three plant nutrients used in our analysis are shown in bold colors in Table 2 for each type of poultry manure. They were the PAN, which is the best estimate of the nitrogen in manure that can be substituted for fertilizer-N, P2O5, and K2O.

Fertilizer Component Prices Used

The price of a pound of fertilizer nitrogen depends of the source. The price data shown previously in Figure 1 shows clearly that the most expensive source of nitrogen was ammonium sulfate, followed by ammonium-nitrate and urea. Ammonium-sulfate, the most expensive source of N, has few advantages unless soil-test results indicate that addition of large amounts of sulfur is needed. Ammonium-nitrate is one of the most common types of nitrogen used to manufacture complete fertilizers. It has the advantage of being water soluble, and is not as readily lost to the air as ammonia as compared to urea. Urea has the advantages of being more water soluble than ammonium-nitrate, and contains 35% more N per ton than ammonium-nitrate. The primary disadvantage of urea is that a significant amount (20% to 40%) can be lost to the air by ammonia volatilization unless it is incorporated in the soil to a depth of at least one inch. So the basic question to decide is: which N-price should be used to define the value of the plant available-N in poultry manure? The price of urea was selected because urea and poultry manure behave similarly with regards to ammonia volatilization losses.

The prices of N, P2O5, and K2O were shown to fluctuate widely from 2000 to 2012 (see Figures 1 and 2). The largest cause of these price fluctuations was the price of energy (i.e. oil) needed to manufacture and transport fertilizers. As a result, the prices of these three major plant nutrients were not allowed to vary independently in the analysis. That is, prices of all three nutrients had to be selected by year because of the dependence of all three on energy prices.

It was not a study objective to try to predict future prices since that would be possible, nor was it to perform calculations for each year. To do so would provide many numbers, but would obscure the basic points to be learned. Instead, the approach used was to select nutrient prices by year and use the years that encompassed the linear increase that began in 2004 as well as major peaks and valleys seen in the price of nitrogen in 2008, 2010, and 2012. Prices were also obtained from market reports to obtain prices for the fourth quarter of 2016 (USDA-SC, 2016; DTN, 2016). The actual prices used by year for the analysis are given in Table 3.

| Table 3. Component fertilizer prices used in the analysis (USDA-ERS, 2013). The prices shown for 2016 were average prices obtained from market publications from the fourth quarter (USDA-SC, 2016; DTN, 2016). | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | $/lb N (Urea) | $/lb P2O5 | $/lb K2O |

| 2004 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.15 |

| 2008 | 0.60 | 0.87 | 0.47 |

| 2010 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.43 |

| 2012 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.54 |

| 2016 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

Value of Poultry Manure Used as a Complete Fertilizer – N,P, and K

The first step in the study was to calculate the value of a ton of poultry manure by multiplying the price of N, P2O5, and K2O for each year (Table 3) by the amount of these nutrients per ton of manure (Table 2). This assumes that all of the nutrients in the manure can be used to grow a marketable crop. This is only true if the soil is poor in fertility or the excess P can be used by other crops in the rotation without application of additional manure. Many brokerage contracts in South Carolina, are based on application of 2 tons of litter per acre prior to a primary crop, such as corn or cotton. Additional litter is not spread on the second crop which is often soybeans. The results for the first step are provided in Table 4.

| Table 4. Variation in the value of various types of poultry manure ($/ton) based on variability in price of N, P2O5, and K2O. Prices assume that all of the nutrients in the manure can be used in a crop rotation. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Broiler (MC = 24%) | Layer (MC = 47%) | Turkey Grow-out (MC = 26%) | Turkey Brooder (MC = 14%) |

| 2004 | 39.09 | 25.59 | 34.61 | 18.91* |

| 2008 | 107.01 | 70.39 | 94.07 | 49.63 |

| 2010 | 79.43 | 50.50 | 68.26 | 36.80 |

| 2012 | 101.10 | 64.56 | 87.06 | 46.68 |

| 2016 | 46.61 | 28.79 | 39.58 | 22.19* |

| * Denotes values too low to be part of a viable brokerage contract with typical brokerage prices being in the range of $20 to $25 per ton of manure. | ||||

The most important observations that can be made from the results given in Table 4 are given below.

- The value of broiler and turkey grow-out litter followed similar fluctuations. The values ranged from about $35 to $39 per ton in 2004 to a maximums of $94 to $107 per ton in 2008. By the end of 2016 the value of turkey grow-out litter and broiler litter ranged from about $40 to $47 per ton. During the years with high fertilizer prices brokerage customers that were paying $40 to $50 to spread 2 tons of litter per acre were receiving much more fertilizer value than they were paying for.

- Turkey brooder litter consistently had the lowest value per ton as compared to the others due to low nutrient content and the large amounts of bedding used. The value of a ton of this type of litter was too low in 2004 and 2016 to be viable for litter brokerage contracts. Even during years with high fertilizer prices (2008 and 2012) turkey brooder litter was rarely brokered since it was so dry. Such dry, low-density manure that was mostly pine shavings further reduced the amount of litter and fertilizer value that could be fit into a typical trailer.

- Layer manure consistently had lower value per ton as compared to broiler and turkey grow-out litter. The lower value was due to the much higher moisture content which diluted the nutrient value of the manure. Layer litter was a viable brokerage option, but not for long haul distances.

Value of Poultry Manure Applied to Fields with Sufficient P2O5

A common situation is when soil-test results indicate that a field has sufficient P2O5 in the soil for not only the crop to be grown immediately, but also for the next crop in the rotation (soybeans for example). In such cases, the P2O5 in poultry manure has no value, and only the N and K2O in the manure can be used as a fertilizer substitute. The results for this situation are provided in Table 5.

| Table 5. Variation in the value of various types of poultry manure ($/ton) based on N and K2O prices. It was assumed that soil-test indicate that no P2O5 was needed. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Broiler (MC = 24%) | Layer (MC = 47%) | Turkey Grow-out (MC = 26%) | Turkey Brooder (MC = 14%) |

| 2004 | 19.95* | 10.80* | 16.05* | 10.50* |

| 2008 | 49.59 | 26.02 | 38.39 | 24.40 |

| 2010 | 43.13 | 22.45* | 33.06 | 20.85* |

| 2012 | 53.58 | 27.84 | 40.98 | 25.80 |

| 2016 | 29.45 | 15.53* | 22.94* | 14.65* |

| * denotes values are two low to be part of a viable brokerage contract with typical brokerage prices being in the range of $20 to $25 per ton of manure. | ||||

The results indicated that when the N price was $0.30/lb and K2O averaged $0.15/lb in 2004 the value of poultry manure was too low to be moved at contact prices of $20 to $25 per ton. Also, at prices associated with 2008, 2010, and 2012 the value of broiler and turkey grow-out litter ranged from $33 to $54 per ton. Layer and turkey brooder litter were poor to marginal values for brokerage contacts when the P2O5 was not needed over the entire range of fertilizer prices.

Comparing the results for 2008 for broiler litter indicates that if P2O5 was not needed the value fell from $107.01/ton to $49.59/ton. That is, the value of the litter was reduced by 54%. The year with the next highest value, 2012, eliminating the need for P2O5 reduced the litter value by 47%. Large drops in litter value can also be observed for other types of poultry manure by comparing the values in Tables 4 and 5. These results indicate that the P2O5 contained in poultry manure is one of the largest sources of value.

Value of Poultry Manure as Only a Source of Nitrogen

The analysis was performed again to reflect the value of poultry manure if nitrogen is the only major nutrient needed based on soil-test results. The results given in Table 6 clearly show that nitrogen alone never provided enough value to support brokerage contracts.

| Table 6. Variation in the value of various types of poultry manure ($/ton) when nitrogen is the only nutrient needed based on soil-test results. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Broiler (MC = 24%) | Layer (MC = 47%) | Turkey Grow-out (MC = 26%) | Turkey Brooder (MC = 14%) |

| 2004 | 11.40* | 6.90* | 10.50* | 7.50* |

| 2008 | 22.80* | 13.80* | 21.00* | 15.00* |

| 2010 | 18.62* | 11.27* | 17.15* | 12.25* |

| 2012 | 22.80* | 13.80* | 21.00* | 15.00* |

| 2016 | 14.06* | 8.51* | 12.95* | 9.25* |

| * denotes values are two low to be part of a viable brokerage contract with typical brokerage prices being in the range of $20 to $25 per ton of manure. | ||||

Results for a Four-House Broiler Farm

The previous results demonstrated that high litter nutrient contents combined with strong fertilizer prices yielded litter values that were much greater than the amount paid to litter brokers. The results also demonstrated that P2O5 was one of the key contributors to litter value. The results of the analysis were applied to a four-house broiler farm to more clearly demonstrate the practical implications. Fertilizer prices from January 2019 in central South Carolina were also added to the analysis. The key assumptions and results are provided in Table 7.

| Table 7. Application of analysis results to a 4-house broiler farm. Building size = 50 ft x 500 ft, litter production was assumed to be 580 tons/year (145 tons/house/yr) with a price of $10/ton paid to the broiler producer ($5800/year). | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | N Price ($/lb) | P2O5 Price ($/lb) | K2O Price ($/lb) | Litter Value ($/ton) | Value of 580 tons of litter ($/Year) | Value from N (%) | Value from P2O5 (%) | Value From K2O (%) | Loss to Producer ($/Year) |

| 2004 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 39.09 | 22,672 | 29 | 49 | 22 | 16,872* |

| 2008 | 0.60 | 0.87 | 0.47 | 107.01 | 62,066 | 21 | 54 | 25 | 56,266 |

| 2010 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 79.43 | 46,069 | 23 | 46 | 31 | 40,269 |

| 2012 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 101.1 | 58,638 | 23 | 47 | 30 | 52,838 |

| 2016 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 46.61 | 27,034 | 30 | 37 | 33 | 21,234 |

| 2019** | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 67.75 | 39,295 | 21 | 53 | 26 | 33,495 |

| * The price paid to a broiler producer in a brokerage contract ranges from 0 to $15/ton of litter. A value of $10 /ton of litter is common. The loss was calculated as: (litter value ($/ton) – $5800). | |||||||||

| ** Prices from central South Carolina obtained in January 2019. | |||||||||

The results indicate that the total value of litter on a four house farms that produces 580 tons of litter per year varied from $22,672 per year in 2004 to a maximum of $62,066 per year in 2008. Currently, the value in January 2019 was estimated to be $39,295/year. In every year, the P2O5 contained in the litter contributed the most to the litter value. This contrasts with the common assumption that the high P2O5 content in litter is a problem as compared to nitrogen. The results point out that the most value can be obtained from litter by giving phosphorous use the priority in manure management. Assuming that the broiler producer was consistently paid $10/ton of litter by the broker the annual litter income was only $5800 per year. If the producer had integrated broiler production with crop production using a rotation that would realize all the fertilizer value in the litter the total litter value would have served to improve profitability of the cropping enterprise. If the producer relied on brokerage as the sole manure management strategy then the annual loss to the producer ranged from $16,872 to $56,266 per year depending on fertilizer prices.

What these results also point to, but do not quantify, is the variation in risk. Producers who built farms using brokerage as the sole manure management plan during the years of high fertilizer prices gave away litter that was worth 3.9 to 10.7 times more than they were paid. They also have incurred a great risk since brokerage contracts typically last only one year, and crop producers who once were happy to purchase brokered litter are no longer consistent customers. Such producers are forced to quickly find other litter use alternatives often in areas where agricultural and forest land may not be close to the farm. Building broiler barns relying on annual brokerage contracts as the sole manure management option has been shown to be short sighted, and has a low probability of being economically or environmentally sustainable. Co-locating poultry production with some sort of profitable plant production enterprise that can use all of the fertilizer value in the litter is preferred. The next most viable alternative may be to use litter to produce high-quality compost for high volume, consistent markets.

What have we learned?

It was found that the value of poultry manure as a complete fertilizer (N,P,K) varied from $18.91 to $107.01 per ton depending of component prices (N, P, K), moisture content, and the amount of bedding used. If the receiving fields did not require phosphorous, based on soil test, the realized value ranged from $10.50 to $49.59 per ton. Finally, if soil-test indicate that N was the only major nutrient needed the value decreased to $7.50 to $22.80 per ton. During the same time frame, brokerage prices ranged from $20 to $50 per ton depending on haul distance and spreading service. However, most brokerage contracts were based on $20 to $25 per ton of manure. Several practical observations were made from the results:

- Brokerage of litter may only be a viable alternative when the receiving cropland needs a complete fertilizer and when the N, P, and K contents of the manure are not diluted by water or bedding.

- Manure brokerage is not economically sustainable if N is the only major nutrient needed by the receiving cropland.

- Integrated farms that can use the manure produced by the poultry barns to fertilize their own cropland have the potential to reduce the legal and economic risk to the execution of a manure nutrient management plan.

- Poultry farms that currently rely on litter brokerage as the only manure management plan are losing customers and need to look at other alternatives that provide a less risky and sustainable use for the mature produced.

- Analysis of the impact of fluctuations in fertilizer price on litter produced from four broiler houses indicated that the full value of the litter ranged from $22,672 to $62,066 per year. The P2O5 contained in the litter accounted for the majority of the fertilizer value (37% to 54%). As a result, complete utilization of litter phosphorous in a crop rotation is the key to realizing the maximum value from litter.

Author

John P. Chastain, Ph.D., Professor and Extension Agricultural Engineer

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Agricultural Mechanization & Business Program, Clemson University, 245 McAdams Hall, Clemson, SC 29634-0312

jchstn@clemson.edu

Sources of Additional Information

Chastain, J.P., J.J. Camberato, and P. Skewes. (2001). Poultry Manure Production and Nutrient Content. Chapter 3B in Confined Animal Manure Managers Certification Program Manual: Poultry Version, Clemson University Extension, Clemson SC, pp 3b-1 to 3b-17. Available at: https://www.clemson.edu/extension/camm/manuals/poultry_toc.html

DTN (2016). Fertilizer Trends: Prices Remain Steady, Mostly Lower from Oct. Available at: http://agfax.com/2016/11/16/dtn-fertilizer-trends-prices-remain-steady-mostly-lower-from-oct/.

USDA-ERS (2103), Fertilizer Use and Price. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/fertilizer-use-and-price/

USDA-SC (2016). Dept of Ag Market News, South Carolina Crop Production Report Dec. 8.

Zublena, J.P., J.V. Baird, and J.P. Lilly. (1997). SoilFacts: Nutrient Content of Fertilizer and Organic Materials (AG-439-18).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Clemson Extension Confined Animal Manure Managers Program.

The authors are solely responsible for the content of these proceedings. The technical information does not necessarily reflect the official position of the sponsoring agencies or institutions represented by planning committee members, and inclusion and distribution herein does not constitute an endorsement of views expressed by the same. Printed materials included herein are not refereed publications. Citations should appear as follows. EXAMPLE: Authors. 2019. Title of presentation. Waste to Worth. Minneapolis, MN. April 22-26, 2019. URL of this page. Accessed on: today’s date.